O sangue

Las jugadas #1

Click here for the English version

En su primer largometraje, O sangue (1989) —rodado en blanco y negro y con escaso presupuesto—, el director portugués Pedro Costa nos proporciona un rico ejemplo de lo que aquí llamaremos jugadas, una detrás de otra. Esta es una película muy cargada pero enigmática sobre la vida familiar y sobre el dramático rito de paso que deben afrontar los chicos tras ser liberados del orden simbólico de sus hogares.

El fragmento en el que me concentraré comprende solo ocho planos que, en total, duran cincuenta y dos segundos. Tiene lugar en el minuto 21 (coincidiendo con el inicio del capítulo 4 del DVD editado por Second Run). Las piezas del relato que nos han conducido hasta aquí se han presentado de forma deliberadamente elíptica, errante, misteriosa. El centro de la trama ha sido, hasta el momento, la difícil relación entre un padre (Canto e Castro) y sus dos hijos, Vicente (Pedro Hestnes) y Nino (Nuno Ferreira). Justo antes de la escena que comentaré, el padre ha muerto, hecho que Vicente está determinado a ocultar a los demás.

De acuerdo a lo que expone Yvette Bíró en su fantástico libro Turbulence and Flow in Film, una de las formas cruciales que adoptan las películas para encontrar y alcanzar su patrón más profundo es la de deambular, la de perderse en desvíos; O sangue procede exactamente de este modo. Cuando llegamos a la escena en cuestión, el filme ya ha dejado atrás, hábilmente, lo que parecía ser su línea principal y se ha abandonado a la tentación de las bifurcaciones: en una secuencia observamos a una profesora, Clara (Inês de Mediros), al cuidado de un grupo de niños pequeños; en otra presenciamos la búsqueda de dos niños fugados cerca de un río. Como veremos, el terreno está siendo preparado, furtivamente, para un gran momento de intensidad, un giro argumental que es dramático pero que está más allá de cualquier lógica estricta (o incluso dúctil) de causa-efecto derivada de las conexiones lineales o narrativas.

Lo que veremos ahora es un fragmento verdaderamente antológico, un momento de puro cine condensado —y ejecutado con los mínimos y más modestos recursos de producción (dos actores principales, algunos niños y objetos, una calle real, un ciclista que pasa)—. Esta escena resuena profundamente en su contexto, pero funciona casi igual de bien para el espectador que la experimenta de modo aislado, fuera del marco narrativo que la contiene.

En el flexible guión de Costa, quizás la acción estuviese expuesta de forma muy breve y simple: en la calle, un hombre (Vicente) sigue, a cierta distancia, a una mujer (Clara); pasa algún tiempo; finalmente, él la alcanza y le formula una pregunta grave. Podemos concebir muchas maneras de poner en escena y filmar esta idea —algunas de ellas muy banales o simplemente funcionales—, y podemos imaginar que la acción es cubierta en muy pocos planos (quizás solo en uno, con un fundido encadenado para marcar la necesaria elipsis temporal) o diseccionada de forma analítica, al estilo de Hitchcock.

Para empezar, debemos notar algo raro e intenso en esta escena. Clara y Vicente no son extraños; anteriormente, durante la búsqueda de los dos niños fugados, nosotros ya les hemos visto juntos. Sin embargo, el comportamiento de Vicente lo hace parecer (hablando en términos de género) un acosador, alguien que espía y sigue el rastro de Clara desde la distancia. Pero O sangue no es un thriller de misterio. En realidad, Vicente está conteniéndose, preparándose, reuniendo el coraje suficiente para hacer a Clara su proposición —cuyo contenido no conoceremos hasta que él lo revele e, incluso entonces, solo elípticamente—. Estos momentos de espera, en los cuales algo no dicho (o todavía no dicho) está agitándose y crepitando —Gorin los llama momentos de saturación, mientras Bíró habla de la absorción mutua o del remolino de energías que precede a la explosión de la turbulencia— son cruciales en las formas internacionales de un cine contemplativo del que, con los años, Costa ha llegado a ser uno de los más importantes representantes.

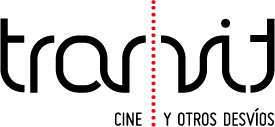

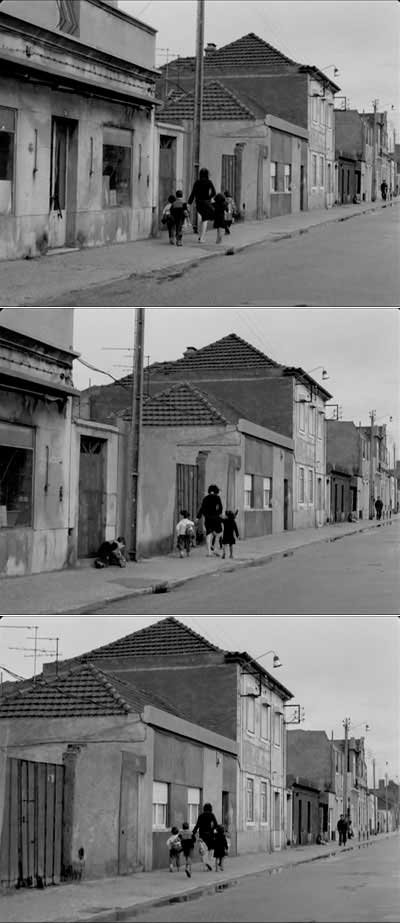

La escena empieza con un plano en el que vemos a Clara acompañando a cuatro niños de la guardería donde ella trabaja. En la banda de sonido escuchamos ruidos ambientales dispersos; no hay música. La cámara de Costa sigue esta acción desde atrás, manteniendo a las figuras en el centro del encuadre; esta distancia (ni demasiado cerca, ni demasiado lejos) deja en medio una buena porción de espacio y permite que la imagen registre muchos detalles de la calle. Sea o no parte del plan de rodaje, al comienzo de esta escena sucede algo que dinamiza el plano: mientras la cámara se mueve siguiendo a Clara y a los niños, uno de ellos se detiene un momento para colocar bien los bajos de su pantalón y, después, corre hasta alcanzar a sus compañeros.

La escena empieza con un plano en el que vemos a Clara acompañando a cuatro niños de la guardería donde ella trabaja. En la banda de sonido escuchamos ruidos ambientales dispersos; no hay música. La cámara de Costa sigue esta acción desde atrás, manteniendo a las figuras en el centro del encuadre; esta distancia (ni demasiado cerca, ni demasiado lejos) deja en medio una buena porción de espacio y permite que la imagen registre muchos detalles de la calle. Sea o no parte del plan de rodaje, al comienzo de esta escena sucede algo que dinamiza el plano: mientras la cámara se mueve siguiendo a Clara y a los niños, uno de ellos se detiene un momento para colocar bien los bajos de su pantalón y, después, corre hasta alcanzar a sus compañeros.

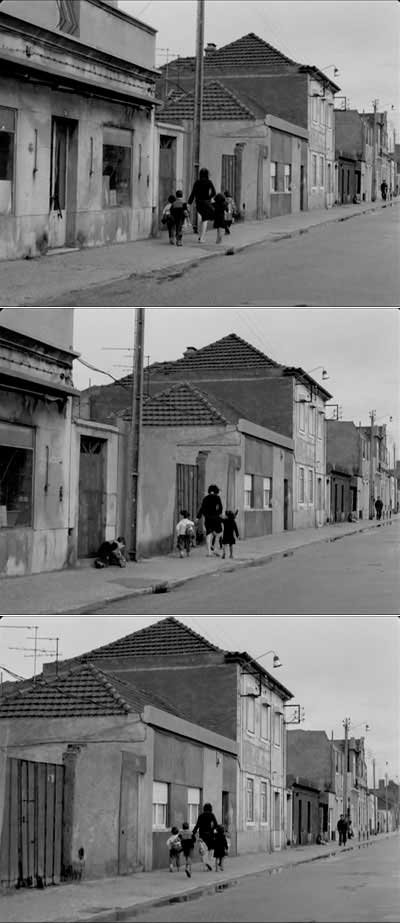

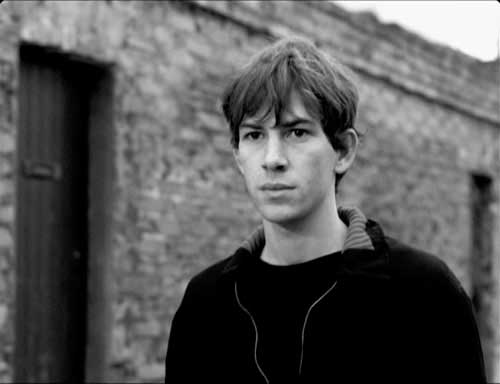

El paso de este plano (1) al siguiente (2) marca la primera jugada. La cámara —esta vez situada frente al personaje— sigue a Vicente, que observa con atención y modera su paso bruscamente. Se trata de un plano medio con una mayor concentración en la figura humana —los detalles de la localización (como el puente que vemos al fondo) ocupan apenas el tercio inferior de la imagen y la cabezade Vicente planea en la blancura del cielo—. Este cambio de plano trae consigo un ligero efecto de shock, similar a las tácticas de sorpresa utilizadas  frecuentemente por Martin Scorsese. Ahora, de forma retroactiva, leemos el plano anterior de otra manera: en él ya no vemos la cámara de Costa siguiendo o registrando una acción, sino que entendemos que se trataba del punto de vista subjetivo de Vicente; la distancia entre la cámara y las figuras es recodificada al instante como la distancia entre Vicente y Clara.

frecuentemente por Martin Scorsese. Ahora, de forma retroactiva, leemos el plano anterior de otra manera: en él ya no vemos la cámara de Costa siguiendo o registrando una acción, sino que entendemos que se trataba del punto de vista subjetivo de Vicente; la distancia entre la cámara y las figuras es recodificada al instante como la distancia entre Vicente y Clara.

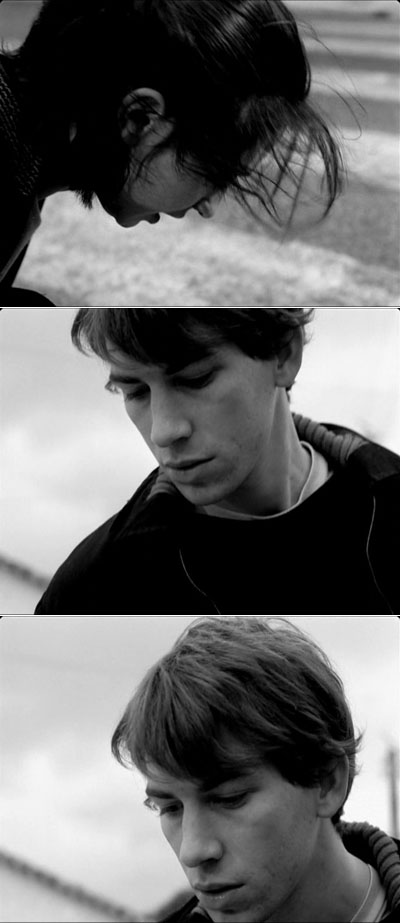

Esto sería un dispositivo  relativamente ordinario en cualquier thriller decente, pero el cambio al plano 3 nos lleva del territorio hitchcockiano al legado bressoniano, muy poderoso en el trabajo de Costa. Aquí ha acontecido una inquietante elipsis: se trata de otro plano de Vicente, pero la luz ha cambiado; el personaje está ligeramente descentrado y completamente rodeado por las fachadas de unas viviendas; su ritmo también se ha enlentecido. Lo único que no ha cambiado es su mirada que permanece tan fija como antes en su objetivo. Este soberbio corte tiene un efecto que es, simultáneamente, concreto y abstracto (y, por lo tanto, se inscribe totalmente en la tradición de Bresson): en un guión, se correspondería con la indicación “más tarde”, pero el intervalo exacto de tiempo elidido (¿minutos?, ¿horas?) es indeterminado. Vale la pena detenerse aquí para advertir la estricta y austera economía de medios estilísticos de esta película: donde muchos otros directores hubiesen optado por proseguir la alternancia entre las tomas móviles de los planos 1 y 2 —o, en la astuta terminología de John Cassavetes, por “cortar y montar por duplicado (double-cut)”—, Costa desecha lo que, para él, son repeticiones redundantes. En sus estrategias formales, Costa conecta y desconecta los planos continuamente al pasar de uno al siguiente —sin duda, el riguroso trabajo con los raccords (cortes en continuidad) y los falsos raccords (cortes discontinuos) es una parte central de su práctica—; pero, al evitar esta alternancia repetitiva de planos, rehúye la tentación de coser, tejer o suturar, de un modo tradicionalmente reconfortante o tranquilizador, la ilusión cinematográfica del mundo ficcional.

relativamente ordinario en cualquier thriller decente, pero el cambio al plano 3 nos lleva del territorio hitchcockiano al legado bressoniano, muy poderoso en el trabajo de Costa. Aquí ha acontecido una inquietante elipsis: se trata de otro plano de Vicente, pero la luz ha cambiado; el personaje está ligeramente descentrado y completamente rodeado por las fachadas de unas viviendas; su ritmo también se ha enlentecido. Lo único que no ha cambiado es su mirada que permanece tan fija como antes en su objetivo. Este soberbio corte tiene un efecto que es, simultáneamente, concreto y abstracto (y, por lo tanto, se inscribe totalmente en la tradición de Bresson): en un guión, se correspondería con la indicación “más tarde”, pero el intervalo exacto de tiempo elidido (¿minutos?, ¿horas?) es indeterminado. Vale la pena detenerse aquí para advertir la estricta y austera economía de medios estilísticos de esta película: donde muchos otros directores hubiesen optado por proseguir la alternancia entre las tomas móviles de los planos 1 y 2 —o, en la astuta terminología de John Cassavetes, por “cortar y montar por duplicado (double-cut)”—, Costa desecha lo que, para él, son repeticiones redundantes. En sus estrategias formales, Costa conecta y desconecta los planos continuamente al pasar de uno al siguiente —sin duda, el riguroso trabajo con los raccords (cortes en continuidad) y los falsos raccords (cortes discontinuos) es una parte central de su práctica—; pero, al evitar esta alternancia repetitiva de planos, rehúye la tentación de coser, tejer o suturar, de un modo tradicionalmente reconfortante o tranquilizador, la ilusión cinematográfica del mundo ficcional.

Hasta el momento: tres planos, dos jugadas. Ahora el ritmo se acelera, la acción se vuelve más densa y, en este intenso combate, entran en juego muchos micromovimientos. En cualquier escena bien realizada, es útil que calibremos la modulación y la articulación de sus elementos en términos de su densificación y de su aligeramiento. Volvemos a ver a Clara, ahora mucho más cerca, entrando en  plano por el lado izquierdo. Ella anda a un ritmo distinto, más brusco, que cuando la vimos anteriormente; los niños han desaparecido del cuadro. Tal y como Jacques Rivette observó en Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964) —y su comentario profetiza todo el trabajo de Costa—, aquí hay muchas cosas que suceden en el corte, de un modo desconcertante, fantasmal.

plano por el lado izquierdo. Ella anda a un ritmo distinto, más brusco, que cuando la vimos anteriormente; los niños han desaparecido del cuadro. Tal y como Jacques Rivette observó en Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964) —y su comentario profetiza todo el trabajo de Costa—, aquí hay muchas cosas que suceden en el corte, de un modo desconcertante, fantasmal.

Entonces, en este cuarto plano, ocurre algo de la categoría de un evento: un ciclista bloquea el camino de Clara y el timbre de su bicicleta se eleva por encima del murmullo de la calle, de los rastros audibles de los pasos, constituyéndose en el primer efecto sonoro verdaderamente individual y distintivo de esta escena.  Clara se detiene, pero la cámara no cesa en su rápido movimiento hacia ella (la energía de este desplazamiento nos recuerda de nuevo a Scorsese o a Samuel Fuller). Ella gira la cabeza y sonríe a una presencia conocida que se encuentra fuera de campo. Pero, mientras la cámara sigue avanzando, seremos testigos de otra jugada sorpresa (tanto en el sentido literal como en el figurado): el brazo de Vicente entra en plano por el lado derecho del encuadre y su mano se posa sobre el brazo de Clara. Esta jugada no estaría fuera de lugar en un filme de Brian De Palma o de Paul Thomas Anderson: lo que, al principio, se presentaba como un punto de vista subjetivo termina transformado en un plano objetivo cuando el que mira penetra en lo que parecía ser su propio campo de visión. Por si fuera poco, en la cadena de reacciones que se dan en estos breves segundos, el gesto de Vicente provoca una pequeña pero notable catástrofe:

Clara se detiene, pero la cámara no cesa en su rápido movimiento hacia ella (la energía de este desplazamiento nos recuerda de nuevo a Scorsese o a Samuel Fuller). Ella gira la cabeza y sonríe a una presencia conocida que se encuentra fuera de campo. Pero, mientras la cámara sigue avanzando, seremos testigos de otra jugada sorpresa (tanto en el sentido literal como en el figurado): el brazo de Vicente entra en plano por el lado derecho del encuadre y su mano se posa sobre el brazo de Clara. Esta jugada no estaría fuera de lugar en un filme de Brian De Palma o de Paul Thomas Anderson: lo que, al principio, se presentaba como un punto de vista subjetivo termina transformado en un plano objetivo cuando el que mira penetra en lo que parecía ser su propio campo de visión. Por si fuera poco, en la cadena de reacciones que se dan en estos breves segundos, el gesto de Vicente provoca una pequeña pero notable catástrofe:  los libros que Clara llevaba bajo el brazo caen al suelo. Mientras ella se agacha, la cámara —que se había detenido en su cabeza inclinada— se mueve para mantener su rostro en primer plano: un movimiento de reencuadre en el característico modo no ostentoso de Fritz Lang.

los libros que Clara llevaba bajo el brazo caen al suelo. Mientras ella se agacha, la cámara —que se había detenido en su cabeza inclinada— se mueve para mantener su rostro en primer plano: un movimiento de reencuadre en el característico modo no ostentoso de Fritz Lang.

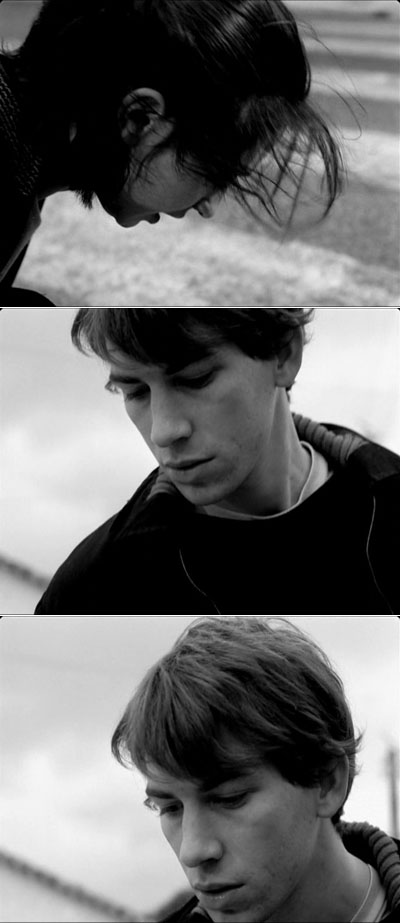

Tras este plano tan cargado, una rápida ráfaga. Plano 5, un breve ángulo contrapicado sobre Vicente crea una rima instantánea de movimientos corporales: si Clara se agachaba, él, al principio, se alza ligeramente (como si estuviese dudando o tuviera miedo) y después vuelve a acuclillarse. Y, además, este breve plano tiene un particular tono emocional: se detiene una fracción de segundo en Vicente y crea una conmovedora complicidad con él. Es un momento clave de absorción-saturación que ocurre mientras él se prepara (como descubriremos enseguida) para articular, por fin, su súplica (que, presumimos, ha sido largamente imaginada o ensayada).

El plano 6 marca un punto crucial  de su interacción: en un juego muy bressoniano de extremidades corporales (encuadradas sobre los libros esparcidos por el suelo), ella agarra la mano vendada de Vicente y le da la vuelta, haciendo visible la sangre que sale de la herida de su palma. En esa transformación —tan constitutiva del estilo de Costa— que convierte la repetición en diferencia, el plano 7 nos devuelve a la misma posición que el 5, pero rápidamente introduce las primeras palabras habladas de la escena: “Salva-me… Só confio em ti”. Esta declaración hermosamente grave, incluso melodramática, constituye, en sí misma, una jugada; aquí, en este gesto verbal, una vida —usando la terminología de Agamben— es puesta en juego: “Una vida ética no es simplemente la que se somete a la ley moral, sino aquella que acepta ponerse en juego en sus gestos, de manera irrevocable y sin reservas, incluso a riesgo de que, de este modo, su felicidad o su desventura sean decididas de una vez y para siempre” (1)↓.

de su interacción: en un juego muy bressoniano de extremidades corporales (encuadradas sobre los libros esparcidos por el suelo), ella agarra la mano vendada de Vicente y le da la vuelta, haciendo visible la sangre que sale de la herida de su palma. En esa transformación —tan constitutiva del estilo de Costa— que convierte la repetición en diferencia, el plano 7 nos devuelve a la misma posición que el 5, pero rápidamente introduce las primeras palabras habladas de la escena: “Salva-me… Só confio em ti”. Esta declaración hermosamente grave, incluso melodramática, constituye, en sí misma, una jugada; aquí, en este gesto verbal, una vida —usando la terminología de Agamben— es puesta en juego: “Una vida ética no es simplemente la que se somete a la ley moral, sino aquella que acepta ponerse en juego en sus gestos, de manera irrevocable y sin reservas, incluso a riesgo de que, de este modo, su felicidad o su desventura sean decididas de una vez y para siempre” (1)↓.

El último plano (8) de la escena ya ha llegado. El ángulo sobre Clara es muy similar al del final del plano 4; podría tratarse de la misma toma o de una distinta, pero la variación viene dada por el hecho de que la cámara se encuentra ahora más cerca de su rostro. Al principio, Clara mantiene la cabeza baja, como si dudara (igual que hizo Vicente momentos antes), pero después la eleva y mira fuera de campo, a los ojos de él. El viento agita sus cabellos que se arremolinan sobre su rostro, la luz es notoriamente distinta  a la de los planos previos —un efecto de sobreexposición, un deslumbramiento saturado que Martin Schäfer, el director de fotografía, ya utilizó en En el curso del tiempo (Im Lauf der Zeit, Wim Wenders, 1976)—. Clara le devuelve la mirada a Vicente y parece dispuesta a contestar a su cuestión de vida o muerte; sin embargo, la respuesta no llega.

a la de los planos previos —un efecto de sobreexposición, un deslumbramiento saturado que Martin Schäfer, el director de fotografía, ya utilizó en En el curso del tiempo (Im Lauf der Zeit, Wim Wenders, 1976)—. Clara le devuelve la mirada a Vicente y parece dispuesta a contestar a su cuestión de vida o muerte; sin embargo, la respuesta no llega.

En lugar de eso, Costa alarga este momento de contemplación abierto. Por primera vez, la música penetra en la escena: notas sampleadas de una pieza orquestal de Stravinsky, frases suspendidas separadas por dramáticos silencios. Entonces, la luz en el rostro de Clara se suaviza mientras comienza un fundido encadenado que nos lleva a la siguiente escena: Vicente conduciendo su moto en el oscuro velo de una noche puntuada por una serie de luces brillantes que cruzan la ciudad (de nuevo, otra muestra del trabajo de Schäfer con exagerados contrastes pictóricos). Costa, deliberadamente, alarga la sobreimpresión de ambas imágenes —el rostro de Clara y la oscuridad nocturna— más tiempo de lo que cabría esperar. Además, en este trabajo con la materialidad de la imagen, sucede algo verdaderamente milagroso y cargado de nostalgia: como en un viejo filme de Hollywood, este efecto especial del encadenado viene acompañado por el uso de la cámara lenta. En un gesto dilatado, Clara parpadea un par de veces; después, mientras ella inclina la cabeza hacia el suelo, Costa introduce un rápido fundido a negro. Cuando este termina, la música continúa y la transición a la siguiente escena ya se ha completado.

En lugar de eso, Costa alarga este momento de contemplación abierto. Por primera vez, la música penetra en la escena: notas sampleadas de una pieza orquestal de Stravinsky, frases suspendidas separadas por dramáticos silencios. Entonces, la luz en el rostro de Clara se suaviza mientras comienza un fundido encadenado que nos lleva a la siguiente escena: Vicente conduciendo su moto en el oscuro velo de una noche puntuada por una serie de luces brillantes que cruzan la ciudad (de nuevo, otra muestra del trabajo de Schäfer con exagerados contrastes pictóricos). Costa, deliberadamente, alarga la sobreimpresión de ambas imágenes —el rostro de Clara y la oscuridad nocturna— más tiempo de lo que cabría esperar. Además, en este trabajo con la materialidad de la imagen, sucede algo verdaderamente milagroso y cargado de nostalgia: como en un viejo filme de Hollywood, este efecto especial del encadenado viene acompañado por el uso de la cámara lenta. En un gesto dilatado, Clara parpadea un par de veces; después, mientras ella inclina la cabeza hacia el suelo, Costa introduce un rápido fundido a negro. Cuando este termina, la música continúa y la transición a la siguiente escena ya se ha completado.

Aplicando un principio derivado de varios maestros minimalistas, Costa apuesta por una estratégica contención estilística que da como resultado el máximo efecto cinematográfico: segundo a segundo —durante los cincuenta y dos que dura esta escena—presenciamos el nacimiento de efectos de sonido, de diálogo y música, de expresivos e inventivos encuadres y movimientos de cámara … Y, lo que aún es más importante, la fuerza de la escena viene dada por el hecho de que esta no termina donde empezó: comienza con un punto de vista subjetivo de Vicente (pese a que esto es señalizado con diez segundos de retraso) y concluye con la experiencia interior de Clara (expresada, no a partir de un punto de vista, sino mediante la conjunción de múltiples elementos: encuadre, decisiones de montaje, pequeños fragmentos musicales, cámara lenta, encadenado…). En menos de un minuto, hemos experimentado un viaje extraordinario, un giro completo: esto son las jugadas. En esta escena realmente ha sucedido algo y nosotros lo sentimos —aunque, en este punto del desarrollo de O sangue, todavía no podamos decir con exactitud de qué se trata—. “Lo demás es psicología”, escribe Agamben, “y en ninguna parte en la psicología encontramos algo así como un sujeto ético, una forma de vida” (2)↓.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

Texto original © Adrian Martin, octubre 2009/agosto 2013 || Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, octubre 2013

(*) Este texto incluye material que fue publicado por primera vez en un capítulo de Film Moments: Criticism, History, Theory, British Film Institute: Londres, 2010, editado por James Walters y Tom Brown.

(1)↑ AGAMBEN, Giorgio: Profanaciones, Adriana Hidalgo: Buenos Aires, 2005, pág. 72.

(2)↑ Ibíd., pág. 94.

The Moves #1: Blood

Click aquí para la versión en español

A rich example of moves, one atop the other, is provided by the Portuguese director Pedro Costa in his low-budget, black-and-white, debut feature Blood (O Sangue, 1989). This is a highly charged but enigmatic film about family life, and the fraught rite of passage for children once they are freed from the ‘symbolic order’ of their home.

The passage on which I will concentrate comprises a mere eight shots, running fifty-two seconds. It occurs twenty-one minutes into the film (coinciding with the beginning of Chapter 4 on the Second Run DVD edition); the pieces of narrative leading up to it have been deliberately elliptical, wandering and mysterious.

The centre of the plot, to this point, would appear to be the difficult relationship between a father (Canto e Castro) and his two sons, Vicente (Pedro Hestnes) and Nino (Nuno Ferreira); just before the scene under discussion, the father has passed away, a fact that Vicente is determined to hide from public knowledge.

According to Yvette Bíró in her great book Turbulence and Flow in Film, one key way that a film finds and reaches its deepest thread is by appearing to meander, to lose itself in detours; Blood proceeds exactly this way. By the time we reach the scene in question, the film has already deftly lost what appeared to be its main thread by following the lure of diversions: the scene of a teacher, Clara (Inês de Medeiros), with the small children in her care; a search for two runaway kids near a river. Stealthily – as we shall see – the ground is being prepared for a major moment of intensity, a turning point that is dramatic but beyond any strict (or even loose) cause-and-effect logic of linear, narrative connections.

What now takes place is a true anthology piece, a condensed moment of pure cinema – executed with modest, minimal production resources (two main actors, a few kids and props, a real street, a passing bicyclist). It resonates deeply in its context, but works almost as well upon an audience who experience it detached, suspended outside of its wider narrative frame.

In Costa’s loose, treatment-like script, the action might have read like this, simply and briefly: a man (Vicente) follows, at a distance, a woman (Clara) along the street. Some time passes. Finally, he catches up to her and poses a grave question. One could imagine many ways of staging and filming this scene – some rather banal, or merely functional. One can also imagine the action being covered in either very few shots (perhaps only one, with a dissolve to mark the necessary temporal ellipse), or analytically dissected into many shots, in a Hitchcockian style.

Something odd and intense about this scene should be noted at the outset. Clara and Vicente are not strangers to each other; we have already seen them search together for the runaway children. And yet Vicente’s action casts him (generically speaking) in the role of a stalker, spying and trailing Clara from a distance. However, Blood is not a mystery-thriller. Clearly, Vicente is holding back, preparing himself and building up the courage to pose his proposition (whose content we do not know until he utters it – and even then, only elliptically) to Clara. Such moments of waiting, in which something unsaid or not-yet-said is stirring and brewing – Jean-Pierre Gorin calls them moments of saturation, while Bíró speaks of the mutual absorption or swirling-together of energies in preparation for the striking turbulence – are crucial in the form of international, contemplative cinema in which Costa has come to be a figurehead in the years since Blood.

In the first shot of this passage, we see Clara accompanying four small children who gather about her – kids from the kindergarten where she works. Sparse natural sound from the street occupies the soundtrack; there is no music. Costa’s camera tracks this action from behind, keeping the figures in the centre of the frame; this distance (neither a conventional close shot nor a conventional long shot) maintains a good deal of space, and registers much detail of the street, in the image. Planned or not, a small bit of business dynamises this opening shot: while the camera, Clara and three children keep moving, a boy in the company has to stop for a moment, fix his trousers, and then catch up with his companions.

In the first shot of this passage, we see Clara accompanying four small children who gather about her – kids from the kindergarten where she works. Sparse natural sound from the street occupies the soundtrack; there is no music. Costa’s camera tracks this action from behind, keeping the figures in the centre of the frame; this distance (neither a conventional close shot nor a conventional long shot) maintains a good deal of space, and registers much detail of the street, in the image. Planned or not, a small bit of business dynamises this opening shot: while the camera, Clara and three children keep moving, a boy in the company has to stop for a moment, fix his trousers, and then catch up with his companions.

The change to shot 2 marks the first move. The camera is tracking in front of Vicente, as he intently watches and briskly paces. It is a mid-shot, with a more focused concentration on the human figure – location detail (such as a background bridge) occupies mainly the bottom quarter of the frame, while Vicente’s head looms in the sky’s whiteness. This shot change carries a slight shock effect which is akin to Martin Scorsese’s  frequent surprise tactics: suddenly we read, retroactively, the preceding shot not as Costa’s camera following or recording the action, but as Vicente’s subjective point-of-view; the distance between camera and figures is instantly recoded as the distance between Vicente and Clara.

frequent surprise tactics: suddenly we read, retroactively, the preceding shot not as Costa’s camera following or recording the action, but as Vicente’s subjective point-of-view; the distance between camera and figures is instantly recoded as the distance between Vicente and Clara.

This would be a common enough device in any decent thriller. But the switch to shot 3 takes us from Hitchcock territory to the Bressonian legacy which is so powerful in Costa’s work. A disquieting ellipse occurs: it is another shot of Vicente, but the light on him has changed, he is now slightly off-centre in the frame, he is completely surrounded by the walls of dwellings, and his pace has slowed; only his gaze on the ‘target’ remains fixed as before. This superb cut is simultaneously concrete and abstract in its effect (and thus fully partaking of the Bresson tradition): it signifies (as in a screenplay indication) ‘later’, but the exact interval (minutes? hours?) is indeterminate. Note, here, the strict, lean economy of stylistic means: where so many other filmmakers would have been tempted to continue the alternation between the mobile set-ups in shots 1 and 2 – to “double-cut”, in the astute terminology of John Cassavetes – Costa pares away such (to him) redundant repetitions. In his formal strategies, Costa continually connects and disconnects the shots in their passage from one to the next – indeed, rigorous work on raccords (match-cuts) and faux-raccords (‘mismatches’) is central to his practice – but, by eschewing the repetition of camera set-ups, he resists the temptation to sew, weave or ‘suture’ the cinematic illusion of a fictional world in any traditionally comfortable or reassuring way.

This would be a common enough device in any decent thriller. But the switch to shot 3 takes us from Hitchcock territory to the Bressonian legacy which is so powerful in Costa’s work. A disquieting ellipse occurs: it is another shot of Vicente, but the light on him has changed, he is now slightly off-centre in the frame, he is completely surrounded by the walls of dwellings, and his pace has slowed; only his gaze on the ‘target’ remains fixed as before. This superb cut is simultaneously concrete and abstract in its effect (and thus fully partaking of the Bresson tradition): it signifies (as in a screenplay indication) ‘later’, but the exact interval (minutes? hours?) is indeterminate. Note, here, the strict, lean economy of stylistic means: where so many other filmmakers would have been tempted to continue the alternation between the mobile set-ups in shots 1 and 2 – to “double-cut”, in the astute terminology of John Cassavetes – Costa pares away such (to him) redundant repetitions. In his formal strategies, Costa continually connects and disconnects the shots in their passage from one to the next – indeed, rigorous work on raccords (match-cuts) and faux-raccords (‘mismatches’) is central to his practice – but, by eschewing the repetition of camera set-ups, he resists the temptation to sew, weave or ‘suture’ the cinematic illusion of a fictional world in any traditionally comfortable or reassuring way.

So far: three shots, two  moves. Now the tempo quickens, the action becomes ‘thicker’, and many micro-moves enter this intimist fray. (It is frequently useful to gauge the modulation and articulation of elements in any well-realised film scene in terms of a thickening and thinning.) We see Clara again, much closer in now, entering the frame from its left side. She is walking at a different, brisker pace than we saw previously, and the children have departed, disappeared. (As Jacques Rivette once noted of Dreyer’s Gertrud [1964] – and the remark is prophetic of Costa’s work as a whole – many things tend to ‘go in the splice’, frequently in a disconcerting, ghostly way.)

moves. Now the tempo quickens, the action becomes ‘thicker’, and many micro-moves enter this intimist fray. (It is frequently useful to gauge the modulation and articulation of elements in any well-realised film scene in terms of a thickening and thinning.) We see Clara again, much closer in now, entering the frame from its left side. She is walking at a different, brisker pace than we saw previously, and the children have departed, disappeared. (As Jacques Rivette once noted of Dreyer’s Gertrud [1964] – and the remark is prophetic of Costa’s work as a whole – many things tend to ‘go in the splice’, frequently in a disconcerting, ghostly way.)

Something like an event then occurs in this fourth shot: a boy on a bicycle blocks Clara’s path, its bell providing the first really distinct, individual sound-effect of the scene, above the murmur of the street and the audible trace of footsteps. Clara stops, but the camera does not cease its quick movement towards her (the energy of this motion recalls again Martin Scorsese, or Samuel Fuller). She turns her head and smiles at the presence off-screen whom she recognises. But then – with the camera still travelling in – there is another surprise move, both in the literal and figurative senses: Vicente’s arm shoots into frame from the right, as he places his hand on Clara’s arm. This move would not be out of place in a Brian De Palma or Paul Thomas Anderson film: what at first appears to be a subjective POV shot is transformed into an objective view, when the ‘looker’ enters what seemed to be the field of his own gaze. On top of all this, in the

Something like an event then occurs in this fourth shot: a boy on a bicycle blocks Clara’s path, its bell providing the first really distinct, individual sound-effect of the scene, above the murmur of the street and the audible trace of footsteps. Clara stops, but the camera does not cease its quick movement towards her (the energy of this motion recalls again Martin Scorsese, or Samuel Fuller). She turns her head and smiles at the presence off-screen whom she recognises. But then – with the camera still travelling in – there is another surprise move, both in the literal and figurative senses: Vicente’s arm shoots into frame from the right, as he places his hand on Clara’s arm. This move would not be out of place in a Brian De Palma or Paul Thomas Anderson film: what at first appears to be a subjective POV shot is transformed into an objective view, when the ‘looker’ enters what seemed to be the field of his own gaze. On top of all this, in the  chain-reaction of these few brief seconds, Vicente’s gesture causes a small but notable catastrophe: Clara drops her books. The camera has halted at her head as she tilts to look down at the ground, and now it whips down with her (a reframing in the unostentatious, Fritz Lang mode), holding the close-up.

chain-reaction of these few brief seconds, Vicente’s gesture causes a small but notable catastrophe: Clara drops her books. The camera has halted at her head as she tilts to look down at the ground, and now it whips down with her (a reframing in the unostentatious, Fritz Lang mode), holding the close-up.

After this very packed shot, a fast flurry. Shot 5, a low angle on Vicente is brief, and creates an instant rhyming of body movements: where she went down, he at first rises slightly (as if in hesitation, or fear), and then lowers himself. And yet this short shot has a particular emotional tenor: it creates a split-second pause on Vicente and a soulful complicity with him, a key moment of absorption-saturation, as he readies (as we will soon discover) to at last speak his (presumably long imagined or rehearsed) entreaty.

Shot 6 then marks a key moment  of their interaction: in a very Bressonian play of bodily extremities (framed against the spilt books on the ground), she grasps his bandaged hand (which he has wounded in a previous scene) and turns it over, revealing the blood seeping from his palm. Shot 7 returns to the same set-up as 5, but – in this transformation of repetition into difference that is constitutive of Costa’s style – instantly introduces the first spoken words of the scene: “Salva-me … Só confio em ti” (English subtitles: “Save me! You’re the only one I trust”). This wonderfully grave, even melodramatic utterance itself constitutes a move: here indeed, in this verbal gesture, a life – to use Giorgio Agamben’s terms – puts itself into play: “A life is ethical not when it simply submits to moral laws but when it accepts putting itself into play in its gestures, irrevocably and without reserve – even at the risk that its happiness or its disgrace will be decided once and for all”. (1)↓

of their interaction: in a very Bressonian play of bodily extremities (framed against the spilt books on the ground), she grasps his bandaged hand (which he has wounded in a previous scene) and turns it over, revealing the blood seeping from his palm. Shot 7 returns to the same set-up as 5, but – in this transformation of repetition into difference that is constitutive of Costa’s style – instantly introduces the first spoken words of the scene: “Salva-me … Só confio em ti” (English subtitles: “Save me! You’re the only one I trust”). This wonderfully grave, even melodramatic utterance itself constitutes a move: here indeed, in this verbal gesture, a life – to use Giorgio Agamben’s terms – puts itself into play: “A life is ethical not when it simply submits to moral laws but when it accepts putting itself into play in its gestures, irrevocably and without reserve – even at the risk that its happiness or its disgrace will be decided once and for all”. (1)↓

The end of the scene (shot 8) has already arrived. The angle on Clara is very similar to where we left her at the end of shot 4; it could be the same set-up or a different take of it, but variation is provided by the fact that the camera is now even closer to her face. At first – again, as if hesitating, as Vicente did only moments ago – she keeps her head down, but then lifts it up, staring off-screen into his eyes.  Wind blows hair across her face, and the lighting is noticeably different from all previous shots: an effect of overexposure, of bleached-out saturation that is familiar from the same cinematographer Martin Schäfer’s work with Wim Wenders on Kings of the Road (Im Lauf der Zeit, 1976). Clara returns Vicente’s gaze and

Wind blows hair across her face, and the lighting is noticeably different from all previous shots: an effect of overexposure, of bleached-out saturation that is familiar from the same cinematographer Martin Schäfer’s work with Wim Wenders on Kings of the Road (Im Lauf der Zeit, 1976). Clara returns Vicente’s gaze and  appears set to respond to the force of his life-or-death question; but no spoken answer comes.

appears set to respond to the force of his life-or-death question; but no spoken answer comes.

Instead, Costa stretches out the open moment of her contemplation. Music intrudes for the first time in the scene: sampled notes from an orchestral piece by Stravinsky, suspended phrases separated by dramatic silences. Then the light on Clara’s face softens as an overlapping dissolve begins: the start of the following scene, Vicente driving his motor bicycle in the dark veil of night that is punctuated by a string of bright city lights (again, an instance of Schäfer’s work with exaggerated pictorial contrasts). Costa deliberately holds the overlay of both images – Clara’s face and the darkness – for longer than might be expected. Plus something truly miraculous, and not a little nostalgic, happens within the materiality of the image-work: as in an old Hollywood film, this ‘special effect’ of the dissolve comes with added slow-motion. After blinking several times in this slowed-down pose, Clara tilts her head back to the ground, and there is a fast fade-out. The music continues, and the transition to the next scene is now complete.

Let us note the principle – no doubt derived by Costa from several minimalist masters – of strategic stylistic withholding for maximal cinematic effect: one by one, during the fifty-two seconds I have considered, we are present at the birth of sound effects, of dialogue, of music, of inventive and expressive camera framings or movements … Even more centrally, where this scene began is, forcibly, not where it ends: it started with Vicente’s subjective point-of-view (albeit with the signalling of this delayed for ten seconds), and it concludes with Clara’s inner experience, conveyed not in a POV gaze but on other, multiple levels: framing, editing decision, musical ‘sting’, slow motion, dissolve. A remarkable journey, and a complete switch-around, in under a minute: these are the moves. Something has truly happened in this scene, and we feel it – even if, at this point of the unfolding of Blood, we cannot yet fully say what it is. “All the rest is psychology”, comments Agamben, “and nowhere in psychology do we encounter anything like an ethical subject, a form of life”. (2)↓

© Adrian Martin October 2009/August 2013

(*) This text adapts material that first appeared in the book Film Moments: Criticism, History, Theory (London: Palgrave Macmillan/British Film Institute, 2011) edited by Tom Brown and James Walters.

(1)↑ Giorgio Agamben (trans. Jeff Fort), “The Author as Gesture” in Profanations (New York: Zone Books, 2007), p. 69.

(2)↑ Ibid., p. 72.