Momentos teen (II)

Ese sentimiento adolescente…

Click here for the English version

Supersalidos (Superbad, Greg Mottola, 2007)

Ricardo Adalia Martín

¿Por qué quiero follarme a la madre de mi amigo? Lo pensaste tantas veces tumbado sobre la cama de tu habitación mientras te masturbabas compulsivamente… ¿A que sí? Un día, como otro cualquiera, fuiste a buscar a tu colega para salir a dar una vuelta. Su madre apareció detrás de la puerta vestida con un mini-short vaquero y una camiseta blanca de tirantes que marcaba y dejaba entrever unos enormes pezones marrones. No llevaba sujetador y te sorprendiste al comprobar que sus tetas todavía estaban a la altura que tenían que estar, pese a sus cuarenta años y un par de hijos a los que había dado de mamar. Descubriste a una mujer bastante apetecible todavía, a la que querías follarte desde la inexperiencia de tus dulces dieciséis. ¡Fantástico!, ahora deseabas integrar en el mismo cuerpo a una mamá y a una puta. Una mujer que, por la mañana, te cuidara como a un niño ofreciéndote la posibilidad de ser padre (y padrastro de tu amigo), y, por la noche, cumpliera con todas tus fantasías sexuales. Un “coito continuo” en palabras del antipático filosofo Otto Weininger, reformuladas posteriormente en imágenes sensibles por el amigable Jean Eustache.

Los hombres debemos vivir este particular momento teen (entre otros tantos) para iniciar el tránsito hacia la edad adulta. Después de formar el mito que integra pasado y futuro de dos mujeres, dos hogares y dos etapas de la vida, estamos obligados a esculpirlo a base de fantasías íntimas y fracasos sentimentales gloriosos para conseguir definir la primera idea de la mujer a la que deseamos. Supersalidos, en su espléndido arranque, atrapa como ninguna otra película esta travesía imprescindible, entre la divagación y lo concreto, que encierra el secreto de la madurez. Seth (Jonah Hill) se dispone a recoger a Evan (Michael Cera) para dirigirse con él al instituto. No puede aguantar un par de minutos: le llama por teléfono desde el coche y comienza a hablarle del “viaje chocholáctico”. Le cuenta que quiere suscribirse a esa web de “tíos que buscan tías por la calle y las invitan a subir a su furgoneta para follárselas”. Le resulta imprescindible porque ofrece una gran variedad de mujeres y de fantasías extremas. Seth piensa constantemente en un sexo completamente idealizado, que no va más allá de las imágenes de las que se ha alimentado. Todo cambia cuando finalmente recoge a Evan, y su madre sale a la calle para despedirles. Ella se agacha y sus voluminosos y carnosos pechos asoman por la ventanilla del vehículo. Cuando ella vuelve a entrar en casa, Seth expresa a Evan sus sentimientos claramente: “Te juro que tengo celos de que chuparas esas tetas cuando eras un bebé”. ¿Qué mejor amante que un eterno lactante? El resto es historia: el camino hacia el primer polvo con esa chica que encarnará la imagen del mito recién formado, solo entonces podrá este ser destruido y superado. De lo contrario… ¿qué más os voy a contar?

© Ricardo Adalia Martín, enero 2013

La leyenda de Billie Jean (The Legend of Billie Jean, Matthew Robbins, 1985)

Yusef Sayed

Billie Jean (Helen Slater) se ha convertido en un foco de atención para los adolescentes de todo el estado. Tras haber escapado, presa del pánico, de la escena de un crimen junto a su hermano (Christian Slater) y sus amigos, huye de la ley, pero pide justicia y proclama su inocencia. Escondida en una casa situada a las afueras de la ciudad, una noche descubre en la televisión una versión cinematográfica de Juana de Arco. No solo se identifica con este personaje y adopta una apariencia similar, sino que poco después también asume su estatus como imagen televisiva. En este punto de autotransformación física y de grabación de su imagen (para ser usada como mensaje destinado a los que la persiguen), es cuando Billie Jean, a su vez, se convierte en un icono. Como muchos adolescentes, su identidad se forma a partir de la imitación de una figura rebelde, y la propia Billie será emulada por sus semejantes.

La imagen grabada e impresa de Billie Jean prolifera, alentada por el frenetismo mediático que se ha montado alrededor de ella; su estilo es absorbido por su hermano, por sus amigos, por adolescentes de todas partes. De mujer joven amenazada a heroína andrógina todopoderosa, la potencia de su imagen pública es evidente, tanto por su rápida circulación como por su habilidad para brotar en todas las formas de representación y fisiologías, como si fuese inherente a ellas. Es la fuente de muchas copias y representaciones, tanto a nivel fotográfico como físico. Así es como la cultura juvenil se propaga, viralmente.

La imagen de Billie Jean es reproducida y vendida por el Sr. Pyatt (Richard Bradford), el propietario de una tienda y el responsable de la huida de Billie. Después de que la motocicleta del hermano de Billie sea destrozada, él accede a hacerse cargo de los daños (ocasionados por su hijo), pero solo a cambio de favores sexuales. Accidentalmente, recibe un disparo mientras los amigos de Billie intentan rescatar a la chica. Equiparando capitalismo y violación, su explotación viciosa de la independencia y la resistencia de la protagonista es lo que le lleva a montar un mercado donde vende artículos relacionados con Billie Jean. Pero, finalmente, estas imágenes se revelan débiles, propensas a la destrucción. Lo que es verdaderamente significante y determina la supervivencia de la protagonista es su buena conciencia, su conducta ética, no los símbolos de rebelión adolescente que son vendidos a las masas.

Billie Jean evita convertirse en una mártir como Juana de Arco. Ella consigue preservar su independencia, separarla de todas esas imágenes que se han ido amontonando. Su estatus icónico se manifiesta, finalmente, en una efigie elevada que ha sido levantada en la playa. Cuando esta empieza a arder, junto al resto de cosas efímeras relacionadas con Billie Jean, los jóvenes se dan cuenta de que todas esas imágenes insustanciales no han traído más que conflictos, desconfianza y conformidad. Sus pancartas de protesta y su sensibilidad por la moda han sido comercializadas, convertidas en producto. Todo adolescente necesita encontrar su identidad personal, única.

El fuego, por lo tanto, lleva la iconografía de Juana de Arco a una inspirada conclusión y termina con la obsesión cultural alrededor de la imagen de Billie Jean. Sus seguidores se dan cuenta de que la estatua es un reflejo de la comercialización muerta, capitalista, y se vuelven contra ella, y lanzan toda la ropa Billie Jean a las llamas. Billie Jean y sus compañeros adolescentes no sufrirán el mismo destino que Juana.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

© Yusef Sayed, enero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

El sur (Víctor Erice, 1983)

Carlos Losilla

Hay ese momento de la bicicleta que se aleja y luego regresa por el mismo camino, en un encuadre idéntico. El sur es una teen movie enmascarada, al igual que El espíritu de la colmena (1973) era una película infantil que se ocultaba en los vericuetos de una fábula histórica. Y ahí, en esa elipsis donde la niña (Sonsoles Aranguren) que se convierte en una adolescente (Icíar Bollaín) que vuelve, en ese paso del tiempo que horada el espacio, se abre un agujero negro que es el tiempo mismo, y también su aparente inmovilidad. Nunca olvidaré las palabras de Estrella: “Crecí más o menos como todo el mundo, acostumbrándome a estar sola y a no pensar demasiado en la felicidad”. Pero las palabras, que se extienden en over por encima de la imagen, se convierten en otra cosa al contacto con ella. Crecer es atravesar el tiempo, herirlo con el instrumento de la lucidez, y por supuesto la venganza del tiempo no se hace esperar, y entonces él también nos atraviesa para decirnos que esa lucidez es conciencia, la conciencia de la espera en soledad de algo que nunca llega. Solo el instante mismo de la imagen transformada que es a la vez imagen casi idéntica a sí misma puede dar una idea del otro lado de esas palabras, ese lado que nunca se nos da a ver, que está en la lejanía del plano, que engulle y vomita al mismo personaje transformado. Y ese lugar lejano puede que no sea un lugar feliz, pero sí impulsa una cierta energía cinemática que pocas veces se ha expresado con tal parquedad, sin estridencias.

Crecer significa la asunción de la soledad y la infelicidad, pero ver crecer, o mejor dicho, no verlo, verlo en una elipsis que nos lo oculta, provoca una exaltación que tiene que ver con la transformación: la niña en adolescente, el mismo camino en otro camino, el cachorro en perro. Todo se convierte ante nuestros ojos en otra cosa, durante unos pocos fotogramas, gracias al impulso de una niña que corre en bicicleta, que hunde las ruedas en el camino, que agujerea el plano al desaparecer. No hay mayor violencia que la que transmite ese trayecto hacia la madurez. No hay mayor rebelión que tomar conciencia, mientras vemos y escuchamos, de que se puede correr hacia un lugar que es el lugar del cine, el que no se ve pero lo cambia todo. Y entonces estar sola es una forma de insumisión. Y no pensar demasiado en la felicidad significa pensar en otras cosas, en la forma de cambiarlas. Por eso Estrella, en ese hiato, se revela una de las teenagers más subversivas de la historia del cine. Regresa de un lugar desconocido para revolucionarlo todo.

© Carlos Losilla, enero 2013

Wild Boys of the Road (William A. Wellman, 1933)

Óscar Navales

Durante el período adolescente que experimenta cualquier ser humano es fácil toparse con determinados acontecimientos, vivencias o conflictos que parecen preludiar lo que aguarda al alcanzar la edad adulta. En general estos momentos conllevan para el individuo la pérdida de una cierta inocencia o candidez, de una determinada ligereza a la hora de caminar por la vida, y pueden ser entendidos como parte del necesario rito de iniciación a los aspectos más amargos, tristes y duros de la existencia.

En el caso de Eddie (Frankie Darro), el adolescente protagonista de Wild Boys of the Road, el primer y conmovedor paso hacia la madurez surgirá como reacción a un inesperado acontecimiento familiar: su padre se ha visto obligado, a consecuencia de los devastadores efectos de la Gran Depresión, a disolver la empresa cementera de la que era propietario, lo que deja la economía de la familia en un estado precario. Eddie no tardará en tomar una decisión que demuestre su apoyo incondicional al núcleo familiar y, con el fin de obtener unos pocos dólares que proporcionen algo de dinero a su progenitor, venderá su querido automóvil al propietario de un negocio de vehículos de ocasión. Pero aunque su acción revela una incuestionable nobleza de espíritu, también implica ciertas renuncias para el personaje, especialmente en lo que concierne a su libertad y desenfado juveniles —transmitidas al espectador en dos instantes muy breves, pero también muy elocuentes y estrechamente relacionados—.

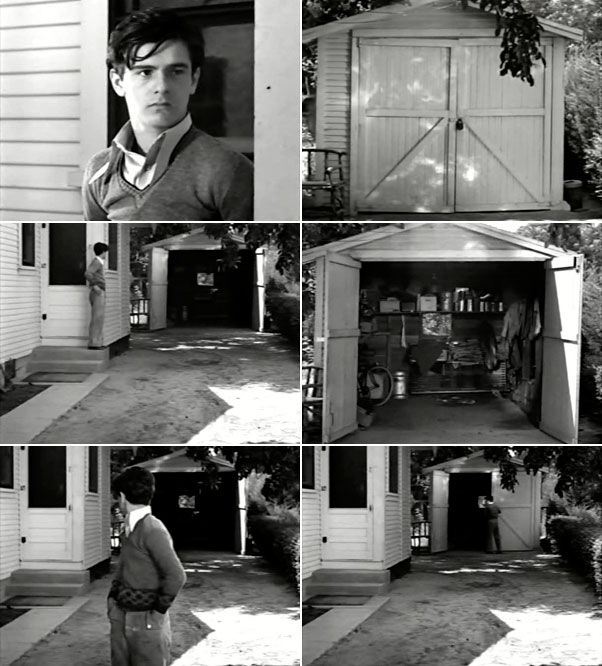

En el primero de ellos, Eddie sale fuera de casa para contemplar a cierta distancia el cobertizo, con las puertas cerradas, en cuyo interior suele aparcar su vehículo. Wellman resuelve la situación de forma harto concisa: introduce un plano medio de Eddie seguido por un contraplano general del espacio que este contempla para, finalmente, retomar el plano del adolescente que continúa observando el cobertizo. Después, mediante un fundido encadenado que nos conduce a un plano del exterior del negocio de coches usados, Wellman expresa la determinación del protagonista.

En el segundo momento, separado del anterior por otras dos secuencias, Eddie repetirá su mirada al cobertizo, tras recibir el cariñoso agradecimiento de su padre por su noble acción. Pero el espacio se mostrará ahora con las puertas abiertas, revelando un vacío en su interior. Wellman repetirá el juego de planos y contraplanos descritos anteriormente, solo que ahora añade a la secuencia un plano general que expresa, de manera dramática e intensa, la relación entre el personaje y ese espacio vacío. Eddie dejará de mirar al cobertizo y empezará a caminar —no muy decidido y fingiendo despreocupación mientras silba We’re in the Money— en la dirección opuesta, hacia la calle, acercándose progresivamente a cámara. A los pocos pasos, el adolescente girará la cabeza hacia atrás, contemplará nuevamente el cobertizo y, respondiendo a un impulso irreprimible de sus sentimientos, correrá a cerrar las puertas para ocultar a la vista ese doloroso vacío. Después la imagen se fundirá a negro.

Por supuesto, con ese gesto, Eddie parece dar por concluida una etapa de su vida: poco después, él y su amigo Tommy se fugarán de sus hogares con la intención de encontrar un trabajo y ganar el suficiente dinero como para regresar algún día y devolver la normalidad a sus familias. Aunque por el camino, desgraciadamente, se toparán con la violencia y agresividad propia de los tiempos que les ha tocado vivir.

© Óscar Navales, enero 2013

Belleza robada (Stealing Beauty, Bernardo Bertolucci, 1996)

Sarinah Masukor

En mitad del filme de Bernardo Bertolucci Belleza robada, Lucy Harmon (Liv Tyler), la protagonista de 19 años, está sola en su habitación, bailando. Sus extremidades se mueven como cohetes propulsados por una energía que no escuchamos. Después el sonido empieza a chorrear en la banda sonora como si nos llegase a través del altavoz diminuto de un walkman, antes de saltar del espacio diegético al cine. La canción es Olympia/Rock Star, el puñetazo de Hole en el estómago suburbano. Tyler lleva puesto un vestido de flores, sus brazos y piernas están en un irreprimible estado de transformación adolescente, y su walkman tiene los mismos auriculares de espuma blanda que se apretaban contra mis oídos noche tras noche, y de los que salía la música a todo volumen de Hole, Babes in Toyland, The Sex Pistols, Bikini Kill, My Bloody Valentine…

Es verano en Canberra, la capital circular de Australia, y yo tengo dieciséis años. Veo Belleza robada tres veces en un viejo cine, el Electric Shadows. El vertiginoso baile de Tyler expresa perfectamente el sentimiento de ese verano. El calor luminoso de la plaza situada en el exterior del centro comercial, la esencia de sándalo de la tienda donde vendían faldas de algodón y sencillas camisas nepalíes, el sabor amargo de los cigarros fumados bajo los arcos del intercambiador del autobús, la pesada ligereza de llevar Martens de ocho agujeros con vestidos de algodón rectos y baratos, el deambular sonámbulo a través de un interminable halo formado por la luz cálida del final de la tarde. Los años adolescentes están extrañamente ligados a un lugar específico, y por eso, para mí, el lugar cinematográfico de Tyler y mi lugar real han quedado inextricablemente unidos. Cada vez que observo su baile, siento los muelles desnivelados de las butacas gastadas del cine, y la raída piel roja que raspa mis piernas desnudas.

Belleza robada no es una buena película. La trama es torpe —un grupo de personajes mayores, ricos y aburridos, que clavan sus ojos en una chica joven mientras ella se prepara para perder su virginidad—, y sus pesadas oposiciones binarias —sexo / muerte; América floreciente / Europa moribunda— la asfixian. Pero el filme está bañado por la luz de la Toscana y la banda sonora es casi perfecta. La cámara no para de moverse. Se desliza sobre el rostro de Tyler, sobre los montes de olivos surcados por el crepúsculo, sobre las finas esculturas de terracota, sobre los suntuosos frescos. La primera vez que escuché Glory Box de Portishead fue en el tráiler del filme donde la imagen de Liv Tyler pedaleando en una vieja bicicleta era traspasada por manchas de luces y sombras. El disfrute aumenta con Mazzy Star, Cocteau Twins, y Liz Phair. Y, por supuesto, están Hole y Tyler, dejándose la piel con los alaridos de Love. Este momento tiene más en común con un centro comercial de Australia que con una villa de la Toscana. Es el sentimiento de tener dieciséis años en el verano de 1996.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

Texto original © Sarinah Masukor, enero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

Abrir puertas y ventanas (Milagros Mumenthaler, 2011)

Carles Matamoros Balasch

Me gusta pensar que las tres hermanas han nacido en Macondo y no en Buenos Aires. O que, al menos, algo le deben Marina (María Canale), Sofía (Martina Juncadella) y Violeta (Ailín Salas) a Úrsula, Amaranta y Rebeca. Pero si le doy demasiadas vueltas a ello los linajes, los roles y las soledades se confunden en mi memoria y me arrastran a una lejana adolescencia de temores, celos y deseos similares. ¿Acaso no es todo una repetición? ¿Una relectura? ¿Una rebelión inútil? Milagros Mumenthaler hereda, al menos, de Gabriel García Márquez una casa semiclausurada. En ese hogar, las habitaciones encierran secretos y los objetos evocan un pasado sin cicatrizar. No sorprende, pues, que también aparezca un fantasma (como el de Melquíades) y que el luto pese como el sopor veraniego.

Todos los rencores, todas las miradas desconfiadas y todos los alejamientos entre ellas tras la muerte de su abuela se diluyen en una escena: aquella en la que las tres escuchan Back to Stay acomodadas en su sofá. La canción de John Martyn emerge como un conjuro capaz de silenciar sus voces y de llevar sus mentes más allá del plano. Cierto que balbucean la letra de la melodía (You know I’m back today, I’m back to stay in your arms), pero en sus rostros vemos que no están ahí sino lejos, mirando en su interior. El encuadre desprende, a su vez, un extraño equilibrio, aquel que permite unirlas por unos instantes mientras cada una muestra su propia individualidad.

¿No habéis tenido antes esa sensación? Encendéis el tocadiscos (o cualquier otro reproductor musical, tanto da) y, de repente, escucháis una canción que os habla a vosotros. Una letra catártica (lo que creéis entender de ella) que os ayuda a descubrir qué os ocurre. Seguramente, mientras esta comunión nacía por primera vez en vuestra habitación, otros adolescentes sentían lo mismo con idéntica melodía. Mumenthaler es capaz de reflejar cómo las canciones (y las películas, y los libros, y…) se dirigen a nosotros y a todos los demás. La música pop, en este caso, no se puede disociar de la adolescencia. Una etapa en la que todo parece ser posible, pero que está irremediablemente condicionada por la aguja de un plato, que nos lleva en un suspiro a otra canción. Lástima, porque durante tres minutos pudimos abrir puertas y ventanas y huir de los cien años de soledad a los que parecemos condenados.

© Carles Matamoros, enero 2013

Confessions (Kokuhaku, Tetsuya Nakashima, 2010)

Covadonga G. Lahera

El contraplano de un adolescente confundido bien podría ser el de una madre aterrada y si, en general, cada uno somos el foco de nuestro mundo porque no nos queda otra, dicha frontalidad parece acusarse más en la pubertad. Confessions me devolvió, entre otras cosas, la existencia de aquel contraplano materno que se ignora en directo durante esa etapa convulsa en la que hasta nuestro propio cuerpo parece un invasor mutante. Substrayendo la trama criminal que articula la película, el minuto escogido refleja el arbitrario y brusco fluctuar adolescente entre dos extremos entre los que se mueve temática y formalmente la película: un inasible silencio y un ineludible alarido. Del mutismo al grito, de la calma al frenesí, de la congelación al aceleramiento: Tetsuya Nakashima sabe cómo registrar tan deformada experiencia del tiempo y en su cinta desdoblada un mismo adolescente puede ser víctima de un torrente emocional y verdugo implacable de yoes más débiles.

Estos sesenta y tres segundos con dos partes diferenciadas pertenecen al capítulo de la confesión de Yuko Shimomura (Yoshino Kimura), madre de Naoki (Kaoru Fushiwara), el estudiante B de la película y uno de los dos chavales involucrados en el crimen de Manami (Mana Ashida). Trascendiendo dicho macguffin narrativo, Nakashima retrata en esos veinte segundos iniciales a una madre enfrentada con el hecho traumático de tener que despedirse de quien ya no es su niño y con la súbita aceptación de un joven desconocido con el que comparte techo y no palabras. La frustración comunicativa es mutua y este arranque que comienza con un grito que la sobresalta acaba una vez más con el obstáculo infranqueable de una puerta cerrada. Naoki permanece fuera de campo, parapetado en su dormitorio. Posible retrato adolescente: un grito ahogado aún sin rostro.

El salto a los siguientes cuarenta segundos es también un corte abrupto. Si el grito apareció por sorpresa, también sale de campo de golpe. Y, entonces, silencio y un idílico álbum de fotos familiar. La madre busca al hijo en ellas y reconoce amargamente un paraíso perdido. Naoki aparece de pronto y le da un susto de muerte. Tan solo un plano en este minuto los registrará juntos. En el resto parecen disputarse el lado más alejado del otro en el encuadre.

El chaval no se reconoce en la foto que le hemos visto sostener previamente a su madre: “¿Quién es este? ¿Por qué diablos sonríe?”. La réplica materna, impotencia y lamento mientras él se mantiene imperturbable. Se cuela repentinamente un plano de los compañeros de clase de Naoki. Ríen y chillan adolescentemente. ¿Por qué se ríen? “Esto es solo una pequeña angustia adolescente. Cuando la supere, verá la luz”, había asegurado el profesor sustituto algunos minutos antes. Si algún día me topo por casa con algún hijo adolescente, lo intentaré con Confessions, por si se le activa el contraplano.

© Covadonga G. Lahera, enero 2013

Roller girls (Whip it, Drew Barrymore, 2009)

Sergio Morera

Es de día, ya casi por la tarde. Llegamos a casa de nuestros padres a los que, por supuesto, olvidamos mencionarles el pequeño detalle de que la noche anterior no volveríamos a dormir. Abrimos la puerta con ligeras dificultades y, de repente, observamos a unas figuras que surgen del final del pasillo. Sí, son ellos. Empieza entonces el fuego cruzado, la clásica batalla paterno filial que termina siempre con la misma víctima apaleada: la juventud.

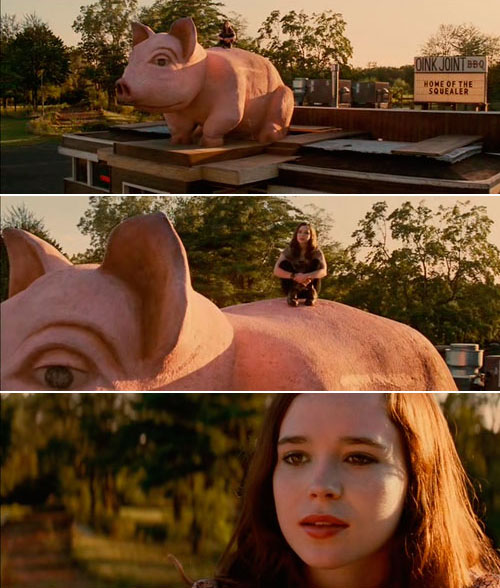

En la vida de un adolescente esta escena es casi tan clásica como lo sería en cualquier película que aborde los conflictos generacionales. Pero, entonces, ¿porqué, al ver esta secuencia en la película Roller girls, me estaba mordiendo las uñas de una mano mientras con la otra estrujaba un cojín? En cuanto me asaltó esta duda, detuve inmediatamente el filme y revisé detenidamente ese momento tratando de buscar algo en su forma (una frase, un gesto) que me aclarase esta sensación. Bliss (Ellen Page) vuelve a casa tras pasar una noche fuera, sus padres le reprochan su actitud basada en un carpe diem sistemático, pelean y la joven se encierra en su cuarto. Una vez más concluí que todo en ella era típico y tópico… pero funcionaba.

Continué, pues, con el visionado y, entonces, justo al final de la película, cuando Bliss está subida sobre un cerdo enorme mirando su ciudad, lo entendí todo: no era la mirada de Bliss la que aparecía en pantalla, ni siquiera la de Ellen Page; era la mirada de Drew Barrymore. En esta secuencia final se notan con mayor fuerza las indicaciones de la directora a la actriz, se percibe un trabajo especial para conseguir de la protagonista esa mirada en concreto, entre alucinada y somnolienta. Un trabajo, en definitiva, que revela ese deseo común en casi todos los cineastas que es filmarse a sí mismos mediante el rostro de otro.

En Roller girls todo encaja. Los desgastados códigos de las teen movies funcionan a la perfección porque este no es un filme más sobre adolescentes, sino un exorcismo, una suerte de ejercicio proustiano personal de Drew Barrymore para conjurar esa adolescencia normal, de pequeños conflictos, que ella jamás tuvo por culpa del cine. Más que en la realidad, la juventud de Barrymore tuvo lugar en los terrenos más oscuros de la ficción y Roller girls es la forma (luminosa) que la realizadora parece haber encontrado para recorrer su imaginario camino de Swann.

© Sergio Morera, enero 2013

Snowtown (Justin Kurzel, 2011)

Laura Ellen Joyce

Snowtown es una reconstrucción libre de los asesinatos reales acaecidos en este ciudad, llamados así porque los cuerpos desmembrados de las víctimas fueron encontrados en la cámara acorazada de un banco abandonado en Snowtown, Adelaida. El nombre del lugar tiene una cualidad mítica, de cuento de hadas, que impregna a la película. La luz mantecosa, los largos travellings por las desoladas áreas rurales, la erosión de la cronología y, finalmente, la vívida fantasía de venganza consumada en la escena de la muerte, todo ello trasciende la banalidad del lugar. La película está contada desde el punto de vista fragmentado del protagonista adolescente, Jamie (Lucas Pittaway), un esquizofrénico de dieciséis año de edad, que sufre el abuso sexual de su vecino y de su hermano mayor, Troy (Anthony Groves). John (Daniel Henshall), su figura paterna —el duende malo—, llega justo en el momento en que Jamie es más vulnerable e interrumpe la persistente dinámica abusiva entre este y su hermano —induciendo a Jamie a convertirse en su cómplice en la violación, tortura, asesinato y mutilación de otros miembros vulnerables de la comunidad—.

La escena más sorprendente de la película llega a mitad de metraje: John, Troy y Jamie están juntos, solos, jugando como niños en una cama elástica. La escena comienza silenciosamente, enmarcada por el azul del cielo. Troy salta y su cuerpo entra y sale del encuadre. Hay un cambio repentino del punto de vista —un plano desde la base de la cama— y, en ese mismo momento, el sonido diegético de los resortes de esta rompe el silencio. John observa las piernas desnudas de Troy mientras este salta. Un plano general hace visible el jardín, situado en la parte trasera de la casa de una sola planta y similar a todas las demás. Este jardín está abarrotado de cosas familiares —un depósito metálico, las bicicletas de los niños y un tendedero en forma de carrusel sobre el que cuelgan algunas ropas desperdigadas—. Algunas partes de la hierba, atravesada por un sucio camino de tierra, están quemadas por el calor. El musculoso cuerpo adolescente de Troy es el foco de atención, ocupa el centro del encuadre. Él salta, desciende y rebota, lleno de fuerza y gracia. Nosotros, como John, lo miramos moverse de arriba a abajo. Jamie entra en el plano. Cuando Troy dice «venga, vamos”, reproduce un diálogo que hemos escuchado en una escena anterior, en la de la violación de Jamie. Esta vez la broma se dirige a John y evidencia la velada amenaza inherente a esta escena. En uno de sus saltos Troy desciende hasta quedar fuera del encuadre y entonces hay un cambio de plano repentino: Troy y Jamie están sentados en el sofá, la cámara nos muestra a John saltando, su tejanos azules y su camiseta negra enfatizan su constitución robusta. Mientras bota y se tambalea torpemente en la cama elástica, los dos hermanos comparten un momento de alegría propiciado por su graciosa apariencia. En este momento, Jamie y Troy se convierten en verdaderos hermanos por un instante —unidos en esa diversión adolescente ante las dificultades de un adulto—. Su juventud y su fuerza los transforman en crueles aliados. Intercalado entre la escena de la violación y la del brutal asesinato final de Troy, este es un momento de alivio pero también de conmoción pues representa vívidamente el abismo entre la infancia y la madurez.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

© Laura Ellen Joyce, febrero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, febrero 2013

La mujer del aviador (La femme de l’aviateur, Éric Rohmer, 1981)

Antoni Peris i Grao

Imberbe emocionalmente y sexualmente bisoño. Así fui durante años. Acostumbrado a películas de acción y en trance de descubrir las obras de Federico Fellini, Stanley Kubrick o Andrej Wajda, el primer visionado de la primera entrega de las “Comedias y Proverbios” de Éric Rohmer sacudió no solo mi intelecto, sino toda mi psique posadolescente.

Como en el grueso de su filmografía, y muy especialmente en esta serie, los protagonistas tienen un objetivo sentimental (y sexual) del que se desvían cuando el azar les plantea otra alternativa, para, finalmente, retomar de nuevo al primer objetivo. En La mujer del aviador o es mejor no pensar en nada François (Philippe Marlaud), un joven enamorado es presa de un ataque de celos porque sospecha que su pareja, Anne (Marie Rivière), tiene un romance con un aviador, Christian (Mathieu Carrière). François la sigue por la calle. Durante su pesquisa, que ocupa la mitad del metraje, es abordado por Lucie (Anne-Laure Meury), una adolescente que se percata de su peculiar actitud. En breve ella se unirá a la investigación y ambos seguirán a la joven y al supuesto amante por el Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Rodada en exteriores soleados y gozando de una extrema naturalidad actoral (él, Marlaud, absolutamente torpe y atribulado; ella, Meury, pizpireta, inquisitiva e incluso seductora), en este filme Rohmer consigue capturar el desplazamiento de los afectos del joven —que pasan de estar focalizados en su novia a centrarse en esta adolescente que empieza a despertar en él (y en todos nosotros) un peligroso interés hacia las menores de edad—.

La larga secuencia absorbe la vivacidad del entorno y se desarrolla con magistral serenidad y fina ironía. A través del personaje de la adolescente, Rohmer sacude de su atolondramiento al protagonista a la par que evidencia ante el espectador la fragilidad de las pasiones humanas, las oscilaciones de la brújula sentimental que debería orientarnos y las innumerables posibilidades de descubrir el amor y las relaciones sentimentales. Love is in the air, parece decirnos. Y basta que sepamos dirigirnos hacia el que más nos interesa, hacia el que más nos conviene. Esta suerte de flirteo sutil, esta manera de identificar un erotismo soterrado en la cotidianeidad, determinaron, en buena medida, no ya mi educación cinéfila sino también la sentimental (al mostrarme que el arte de la seducción no tiene límites de edad, sexo ni situación).

No me arregló la vida pero me ayudó a entender las inmensas posibilidades de la obra cinematográfica en particular y del amor en general. Eso sí, hoy sigo siendo un pringado para con las mujeres y enamorándome, en uno u otro momento, de todas las que encuentro. Sin ir más lejos, de todas las fascinantes redactoras de Transit.

© Antoni Peris i Grao, enero 2013

That teenage feeling …

Click aquí para la versión en español

Superbad (Greg Mottola, 2007)

Ricardo Adalia Martín

Why do I want to fuck my friend’s mother? You’ve thought this so many times lying on your bed in your room, while compulsively masturbating … Right? One day, like any other, you went to pick up your mate to go for a drive. His Mum appeared at the door, dressed in denim mini-shorts and a white, striped T-shirt that outlined and implied a pair of enormous, brown nipples. She wasn’t wearing a bra, and you were amazed to see that her boobs were still at their previous height, despite their forty years, and a couple of sons who had sucked them dry. All the same, you want to fuck her, since – with all your ‘sweet sixteen’ inexperience – you find her to be quite an attractive lady. Great! Now you want to bring together, in the same body, Mother and Whore. A woman who, by day, you care for like a child, thus offering you the chance to be a father (and your pal’s stepfather); and at night she fulfills all your sexual fantasies. ‘Continuous coitus’, according to the ungenial philosopher Otto Weininger – subsequently reformulated into material images by the highly genial Jean Eustache.

Guys must live out this particular teen moment (among many others) in order to enter the transition to manhood. Having formed the myth that fuses the past and future of two women, two homes and two life phases, we are then obliged to start building – on the basis of intimate fantasies and glorious sentimental disasters – the defining, initial idea of the kind of woman we really want. Like no other movie, Superbad captures, in its splendid opening scene, this essential journey, this movement between digression and concreteness, that will hold the very secret of adulthood. Seth (Jonah Hill) is driving to school and picking up Evan (Michael Cera) on the way. He cannot wait even a few minutes to tell his friend by phone about the ‘Vagstastic Voyage’. He explains what you will see by subscribing to the website of this name: ‘They find, like, random girls on the street and they invite them into a van, and then they bang them once they’re on the van’. The site is amazeballs because it offers a wide variety of chicks, plus the most extreme fantasies. Seth forever imagines a totes idealised sexuality, informed by nothing but the images he worships. But it all changes once he eventually picks his friend up, and Evans’ Mum comes out of the house to farewell them. She bends over; her weighty, fleshy breasts expose themselves to the view from inside the vehicle. When she goes back in the house, Seth expresses his emotions quite unambiguously to Evan: ‘I am truly jealous you got to suck on those tits when you were a baby’. I ask you: what better lover than an eternal breastfeeder? The rest is history: the road to the first fuck with the girl who incarnates the image of this newly-formed myth – which only then can be destroyed and surpassed. Otherwise … do you want me to go on?

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Ricardo Adalia Martín January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

The Legend of Billie Jean (Matthew Robbins, 1985)

Yusef Sayed

Billie Jean (Helen Slater) has caught the attention of teens across the state. She is on the run from the law, after fleeing the scene of a crime in a state of panic with her brother (Christian Slater) and friends, but she demands justice, proclaiming her innocence. Hiding out in a house in the suburbs at night, she discovers a film version of Joan of Arc showing on the television. Not only does she identify with Joan and adopt a similar appearance; she soon after takes on her status as a televisual image, too. It is at this point of physical self-transformation and the recording of Billie Jean’s image – for use as a message to her pursuers – that she, in turn, becomes an icon. Like a lot of teens, her identity is shaped through the imitation of a rebellious figure, and Billie herself is emulated by her peers.

The recorded and printed image of Billie Jean proliferates, encouraged by the media frenzy whipped up around her; her style is absorbed by her brother, her friends and teenagers far and wide. From threatened young woman to all-powerful, androgynous hero, the potency of the ‘Billie Jean’ persona is apparent through its speedy circulation and its ability to inhere in all media and physiologies. It is the source of many copies and representations, at the photographic and physical level. This is how youth culture spreads, virally.

Billie Jean’s image is reproduced and sold by Mr Pyatt (Richard Bradford), the shop owner who is responsible for Billie’s flight. After Billie’s brother’s motorcycle is vandalised, he agrees to pay for the damages – caused by his son – but only in exchange for sexual favours. He is accidentally shot as Billie’s pals try to rescue her. Equating capitalism with rape, it is his vicious exploitation of Billie Jean’s independence and defiance that leads to a market in Billie Jean merchandise. But these images are ultimately weak, prone to destruction. It is Billie Jean’s good conscience, her ethical conduct, that are significant and which determine her survival – not the symbols of teen rebellion that are sold to the masses.

Billie Jean avoids becoming a martyr like Joan of Arc. She retains her independence from the images of her that have accumulated. Her iconic status is finally manifested as a towering effigy, at the beach. When it is set alight, along with the rest of the Billie Jean ephemera, the realisation among her peers is that these insubstantial images have wrought so much conflict, suspicion and conformity. Their protest banners and fashion sensibility have been commodified. Each teenager needs to find their unique, personal identity.

The fire, then, takes the Joan of Arc iconography to an inspired conclusion, and it ends the cultural obsession with the image of Billie Jean. The youths realise that the statue is a reflection of dead, capitalist branding and they turn on it, throwing their Billie Jean clothing into the flames. Billie Jean and her fellow teens will not suffer the same fate as Joan.

© Yusef Sayed January 2013

El sur (Víctor Erice, 1983)

Carlos Losilla

It’s the moment of the bicycle that goes away and later returns along the same road, identically framed. El sur is a disguised teen movie, just as The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) was a children’s film hiding in the intricate folds of a historical fable. And there, in that ellipsis where the girl (Sonsoles Aranguren) is transformed into an adolescent (Icíar Bolláin) who is coming back, in this passage of time that punches a hole in space, there opens a black hole which is time itself, but also signals its seeming immobility. I will never forget Estrella’s words: ‘I grew up more or less like everybody else – I got used to be being alone, and didn’t think too much about happiness’. But these words, which play over the image just described, become something else when mixed with it. To grow up is to pass through time, to wound it with the instrument of lucidity – and, of course, time’s revenge is unexpected, for it also passes through us, to let us know that this lucidity is consciousness, the consciousness of waiting, alone, for something that never arrives. Only the precise instant of the transformed image, which is at once almost identical to its partner image, can give us some idea of the other side of these words, the side we are never allowed to see – namely, the faraway distance in the shot, which swallows and then regurgitates the same, changed character. And this distant place may not be a happy one, but it indeed drives a certain cinematic energy that has seldom been expressed with such minimalism, without any bombast.

To grow up means accepting loneliness and unhappiness; but to see growth or, better still, not see it – to see it within an ellipsis that hides it from us – this stirs an exaltation related to transformation: the girl into the adolescent, the same road into a different road, the puppy into the dog. In front of our very eyes, in the space of just a few frames, everything becomes something else – thanks to the motion of a girl who rides her bicycle, who sets her wheels upon the ground, who slashes the shot until it vanishes. There can be no greater violence than the violence conveyed by this trip to maturity. No greater rebellion than becoming aware, as we watch and listen, that we can flee to a place which is precisely cinema’s place – which we cannot see, but that changes everything. And so, being alone is a form of insubordination. And not thinking too much about happiness means being able to think about other things, and how to alter them. That is how Estrella, in this gap, is revealed to us as one of the most subversive teens in cinema history. She comes back from an unknown place to revolutionise everything.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Carlos Losilla January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin February 2013.

Wild Boys of the Road (William A. Wellman, 1933)

Óscar Navales

During the adolescent phase lived by every human being, it is easy to encounter certain events, experiences or conflicts that would appear to be preparations for what is regarded as adulthood. Generally, such moments involve, for the individual, the loss of a certain innocence or naïveté, a particular lightness when moving along life’s road. This can be understood as part of the necessary rite of passage toward sadder, more difficult or bitter aspects of life.

In the case of Eddie (Frankie Darro), the adolescent hero of Wild Boys of the Road, the poignant first step to maturity occurs as the result of an unexpected family incident: his father is forced by the devastating effects of the Great Depression to dissolve the cement company he owned – thus leaving his family in a precarious state. Eddie does not hesitate to make a decision that demonstrates his unconditional support of the family unit. With the intention of raising a bit more money for his folks, Eddie sells his beloved car to the owner of used car yard. Although his act reveals an undeniably noble spirit, it also implies certain renunciations on his part, especially in relation to his youthful freedom and comfort – communicated to the spectator in two quite closely related, brief, but quite eloquent moments occurring within the film’s first twenty minutes.

In the first moment, Eddie leaves the house to contemplate, at a certain distance, the closed doors of the garage shed where his car is usually parked. Wellman articulates the situation extremely concisely: beginning with a mid-shot of Eddie, followed by a wide reverse-shot of space he is looking at, and finally returning to the shot of the teenager – who keeps contemplating the garage until he exits the frame. This is how, using a lap-dissolve that takes us to an exterior view of the automobile junk yard, Wellman expresses his character’s determination.

In the second moment – separated from the first by two intervening scenes – Eddie reprises his look at the garage, straight after receiving the affectionate gratitude of his father for his noble action. But the site is now displayed with its doors open, revealing the vacuum inside. Wellman repeats the game of shot/reverse-shot already described, except that that now he also adds to the scene a wider shot that expresses, in a dramatic and intense way, the relationship between the character and the empty space. After looking over at the garage, Eddie starts to walk – not very decisively, feigning indifference whistling ‘We’re in the Money’ – in the opposite direction, toward the street, moving progressively closer to the camera. But a few steps along, this teenager turns his head, gazes once more at the garage and – responding to an irrepressible surge of emotion – runs to close its doors, hiding from view that awful emptiness. The image then fades to black.

Of course, with this gesture, Eddie seems to conclude one phase of his life: shortly afterwards, he and his friend Tommy flee from their homes, with the intention of finding a job and earning enough money to return someday and restore normality to their families. But along the way, unfortunately, they encounter the violence and aggressiveness of the time in which they live.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Óscar Navales January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013.

Stealing Beauty (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1996)

Sarinah Masukor

In the middle of Bernardo Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty, nineteen-year-old Lucy Harmon (Liv Tyler) is alone in her bedroom, dancing. Her limbs rocket around; propelled by some unheard energy. Then the sound trickles onto the soundtrack as if through tinny Walkman speakers, before leaping out of the diegesis and into the cinema. The song is “Olympia/Rock Star”, Hole’s punch in the suburban stomach. Tyler is wearing a floral print dress, her arms and legs are in an irrepressible state of teenage becoming, and her walkman has the same soft foam headphones that pressed into my ears night after night, screaming with Hole, Babes in Toyland, Sex Pistols, Bikini Kill, My Bloody Valentine …

It is summer in Australia’s circular capital Canberra, and I am sixteen. I see Stealing Beauty three times in the old Electric Shadows cinema. Tyler’s giddy dancing expresses perfectly the feeling of that summer. The bright heat of the square outside the mall, the sandalwoody scent of the shop that sold Indian cotton skirts and striped Nepalese shirts, the acrid taste of cigars smoked under the arches at the bus interchange, the heavy lightness of wearing 8 hole docs with cheap cotton shifts, and the somnambulant drift of wandering through an endless haze of warm, late afternoon light. Teenage years are strikingly site-specific, and so Tyler’s cinematic place and my real one have become inextricably linked in my being. Whenever I see her dance, I feel the uneven springs in the worn cinema seats, and the scratch of torn red leather against bare legs.

Stealing Beauty is not a good film. The plot is heavy-handed – a bunch of rich, bored, old people ogle a young girl as she prepares to lose her virginity – and marred by clunky binaries: sex/death; blooming America/dying Europe. But it is filled with Tuscan light and the soundtrack is near perfect. The camera never stops moving. It glides over Tyler’s face, the dusky olive hills, the smooth terracotta sculptures, the sumptuous frescos. I first heard Portishead’s “Glory Box” in the film’s trailer, over an image of Tyler riding an old bike through dappled shade. Mazzy Star, Cocteau Twins, and Liz Phair add to the glow. And of course, there is Hole and Tyler kicking it to Love’s howls. It is a moment that has more in common with an Australian mall than a Tuscan villa. It is the feeling of being sixteen in the summer of 1996.

© Sarinah Masukor January 2013

Back to Stay (Abrir puertas y ventanas, Milagros Mumenthaler, 2011)

Carles Matamoros Balasch

I’d like to think that these three sisters were born in Macondo, not Buenos Aires. Or, at least, instead of being named Marina (María Canale), Sofía (Martina Juncadella) and Violeta (Ailín Salas), they are really Úrsula, Amaranta and Rebeca. Maybe I am allowing too great a leeway to the family bloodlines, roles and solitudes that are mixed up in my memory, and that drag me back to a faraway adolescence of similar fears, jealousies and desires. But isn’t everything a repetition? A re-reading? A futile rebellion? Milagros Mumenthaler inherits, at the very least, a half-shut house from Gabriel García Marquez. In this home, rooms contain secrets, and objects evoke a past that won’t heal. Hardly a surprise, then, when a ghost (like Melquíades) turns up, and that grief weighs everything down like a summertime slumber.

All the grudges, all the suspicious looks and all the separations that have passed between them since their grandmother’s death – all dissolve in the course of a particular scene: where the trio listens to “Back to Stay” (also used for the film’s English title), comfy on the sofa. John Martyn’s song rises like a spell capable of silencing their voices and taking ther minds beyond the shot. Certainly, the song lyrics prattle on (“You know I’m back today / Back to stay in your arms”), but we can see on their faces that they are not here but far away, looking deep inside. The framing of the shot achieves, in turn, an odd equilibrium: allowing us to join them for a few moments, as each displays her own individuality.

Haven’t you had this feeling before? You turn on your record player (or whatever kind of music appliance you have, it doesn’t matter), and suddenly you hear a song that speaks to you. It’s like a cathartic message (at least, as you think you understand the lyrics) which helps you grasp the things happening to you. And surely, while this moment of communion seemed to be born for the very first time in your own room, other teens have felt the exact same thing to the exact same song. Mumenthaler is able to reflect on how such songs (and films and books and …) are directed at us, and everybody else as well. Pop music, in this case, cannot be dissociated from adolescence. A phase in which all seems possible, but that is irremediably determined by the record player’s needle – which takes us, in a breath, to the next song. Which is a pity because, for those three minutes, we can open the doors and windows to escape the hundred years of solitude to which we seem condemned.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Carles Matamoros January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013.

Confessions (Kokuhaku, Tetsuya Nakashima, 2010)

Covadonga G. Lahera

The reverse-shot of a confused teenager could well be a horrified mother; if, generally, each one of us is the focus of our own world because we can hardly focus on anything else, such frontality seems to confront us most at puberty. Confessions took me back to (among other things) the existence of this maternal reverse-shot that is ignored in its direct state during this turbulent phase, in which even our own body looks like a mutant invader.

Eliminating the criminal plot that structures the film, my chosen minute reflects the arbitrary, brusque fluctuation of a teenager between two extremes that drive the movie both thematically and formally: an elusive silence, and an inescapable cry. From mutism to screaming, from calm to frenzy, from being frozen to sudden speed-up: Tetsuya Nakashima knows how to register this deformed experience of time, and in its unfolded ribbon the same teen may be the victim of an emotional tidal wave and also the implacable executioner of weaker egos.

These sixty-three seconds, in two distinct parts, belong to the chapter devoted to the confession of Yuko Shimomura (Yoshino Kimura), mother of Naoki (Kaoru Fushiwara) – named ‘Student B’ in the film, and one of two kids involved in the crime committed upon Manami (Mana Ashida). Transcending this narrative MacGuffin, Nakashima depicts, in the first twenty seconds, a mother confronted with the traumatic prospect of having to say farewell to the person who is no longer ‘her child’, and having to suddenly accept that this unknown youth shares the same house as her, but not the same language. The communication breakdown is mutual; this outburst that begins with a cry will startle her once again with the insurmountable obstacle of a closed door. Naoki stays off-screen, shut up in his bedroom. One possible adolescent portrait: a scream that is suffocating, but faceless.

The transition to the next forty seconds is, again, by an abrupt cut. If the scream appears by surprise, it also eludes being framed. Then there is silence, and an idyllic album of family photos. The mother finds her son among them, bitterly recognising a lost paradise. Naoki suddenly appears and scares her almost to death. Only a single shot in this minute frames both of them together. For the rest of the time, they each seem to combatively address the far side of the frame, the side of the Other.

The boy doesn’t recognise himself in the photos we have just seen his mother holding: ‘Who’s this? Why the hell is he smiling?’ The maternal response is impotent and teary, while the son remains unmoved. A shot of Naoki’s classmates suddenly slips in. They are laughing and shrieking like teens. Why are they laughing? ‘It’s just some minor teenage angst. When you get over it, you’ll see the light’ – this is what the substitute teacher said, some minutes previously. If, one day, I come up against a teenage boy like this at home, I’ll try Confessions out on him – to see if it triggers the reverse-shot.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Covadonga G. Lahera January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin February 2013.

Whip It (Drew Barrymore, 2009)

Sergio Morera

It’s daytime, already almost afternoon. We’re landing back at our parents’ home – having neglected to mention to them the little detail that we were not returning to sleep there the night before. We open the door with some difficulty and, suddenly, see those figures emerging at the end of the hallway. Oh yes, there they are! Time for the crossfire to begin, the classic parent-child battle that always ends with the same, depleted casualty: youth.

This scene is almost as classic in any adolescent’s life as it is in just about any film that tackles the generation gap. So why, as I beheld this moment in Whip It, was I biting the nails of one hand, while clutching a pad with the other? As soon as this thought hit me, I instantly stopped the movie and reviewed the sequence carefully, trying to find the thing – a phrase, a gesture – that, in its materiality, could clarify my feeling. Bliss (Ellen Page) has come home after a night out; her parents scold her attitude derived solely from a carpe diem mentality, they all argue … and the young lady locks herself in her room. Again, I had to conclude that everything here was typical, topical … yet, somehow, it worked.

So I kept on watching – and, just at the end of the film, when Bliss is sitting on top of a huge, shop-rooftop pig overlooking the town, I finally understood everything: it wasn’t Bliss’ perspective registered on screen, nor even Page’s – it was Drew Barrymore’s. In this final scene, what appears, with particular force, are the director’s indications to her actress; what we perceive is the special work required to draw from the character this specific look, somewhere between spaced-out and dreamy. A labour, in short, that reveals this desire shared by almost every director when they film themselves via the face of another.

In Whip It, everything fits. The worn-out teen movie codes work perfectly, because this is not a film about teenagers – rather, it is an exorcism, a kind of personal, Proustian exercise on Barrymore’s part. Whip It conjures the normal adolescence, with its petty conflicts, that she never had – precisely because of her life in movies. In reality, Drew’s youth unfolded in far darker places than we see in this story. So the film offers the (luminous) form that this director appears to have discovered in the process of recounting her own, imagined ‘Swann’s way’.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Sergio Morera January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013.

Snowtown (Justin Kurzel, 2011)

Laura Ellen Joyce

Snowtown is a re-imagining of the true events of the Snowtown murders; so-called due to the dismembered bodies of the victims being found in a disused bank vault in Snowtown, Adelaide. The name of the location has a fairytale, mythic quality which permeates the film – the buttery light, the long tracking shots of desolate outback, the erosion of chronology, and, finally, the vivid revenge fantasy death scene, all transcend the banality of the location. The film is from the fragmented point of view of the teen protagonist, Jamie (Lucas Pittaway), a sixteen year old schizophrenic, who is sexually abused by a neighbour, and by his older brother, Troy (Anthony Groves). John (Daniel Henshall), his bad-fairy father figure, comes in at just the moment when Jamie is most vulnerable, and irrupts the persistently abusive dynamic between Jamie and his brother – inducting Jamie into being his accomplice in the rape, torture, murder and mutilation of vulnerable members of the community.

The most striking scene in the film comes about halfway through – John, Troy and Jamie are alone together, playing, like children on a trampoline. The scene begins silently – framed by blue sky, Troy jumps in and out of shot. There is a sudden shift of POV to the base of the trampoline. At the same moment the diegetic sound of the springs of the trampoline breaks the silence. John watches Troy’s bare legs as he jumps. The shot pans out and the yard, backing on to the one-story tract house, is visible. The yard is cluttered with family ephemera – a metal silo, children’s bikes and a carousel washing line, scattered with a few clothes. The grass is partially heat-scorched and a dirt track runs through it. Troy’s muscular teenaged body is the focal point, at the very centre of the frame. He jumps, dips and bounces with grace and strength. We, like John, watch as he moves up and down. Jamie arrives into the shot. When Troy says “Let’s go, come on” he reproduces dialogue from earlier in the film, from the scene where he raped Jamie. This time, the teasing is aimed at John, and shows the thinly veiled menace inherent in this scene. Troy dips low, there is a sudden shift, and Troy and Jamie are seated on the sofa, the camera cuts to show John bouncing – his blue jeans and black top emphasising his stocky build. As he flails and wobbles, the two brothers join in a moment of delight at his amusing appearance. At this moment, Jamie and Troy become true brothers for an instant – united in teen amusement at the failings of an adult. Their youth, and strength make them cruel allies. Sandwiched between the earlier scene of rape, and the final, brutal, murder of Troy, this scene allows both respite and poignancy – and the chasm between childhood and adulthood is vividly played out.

© Laura Ellen Joyce February 2013

The Aviator’s Wife (La femme de l’aviateur, Éric Rohmer, 1981)

Antoni Peris i Grao

Emotionally immature and sexually inexperienced: that’s how I was for years. Accustomed to action movies, and in the midst of the trance induced by discovering Federico Fellini, Stanley Kubrick and Andrzej Wajda, my first viewing of the inaugural entry in Éric Rohmer’s Comedies and Proverbs series shook not only my intellect, but also my post-adolescent psyche.

As in the bulk of his filmography, and especially the Comedies and Proverbs, Rohmer’s protagonists start with a sentimental (and sexual) goal from which they then deviate when fate leaves them with no alternative – in order, finally, to return once more to their first target. In The Aviator’s Wife, or ‘One Can’t Think of Nothing’, François (Philippe Marlaud), a 20-year-old romantic, is plagued by a fit of jealousy because he suspects that his older girlfriend, Anne (Marie Rivière), is having an affair with an air pilot, Christian (Mathieu Carrière). François follows his rival down the street. During his research, which occupies half the film, he is approached by Lucie (Anne-Laure Mery), a teenager who has fathomed his peculiar mission. She swiftly joins the investigation, and so they follow Christian and his assumed lover through the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Shot in sunny exteriors and benefitting from an extreme naturalness in the acting (Marlaud as François is completely awkward and morose; while Meury as Lucie is doting, inquisitive, even seductive), Rohmer manages to capture here the displacement of young people’s affections – which pass, in François’ case, from being focused on his girlfriend to centring on this teenager who begins to awaken in him (and us) a dangerous interest in under-age minors.

This long sequence absorbs the liveliness of its surroundings, and develops with masterful serenity as well as a delicate irony. Through the teen character, Rohmer shakes the hero out of his befuddlement, and uncovers the evidence for we spectators of the fragility of human passions, the waverings of the emotional compass that should guide us, and the countless possibilities for discovering love and romantic relationships. Love is in the air, the film seems to say. We merely need to head towards the person who most interests us to find the one who best suits us. This kind of subtle flirtation, this manner of identifying an eroticism buried in the everyday: it determined, to a large degree, not only my cinephile education but also my sentimental education – teaching me, for instance, that the art of seduction knows no limits, whether of age, sex or situation.

The film didn’t fix up my life, but it did help me understand the immense possibilities of cinematic art in particular, and of love in general. So yes, these days I’m still a ‘fool for love’, falling (in one moment or other) for every woman I meet – such as, to go no further, all the fascinating lady-writers of Transit!

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Antoni Peris i Grao January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013