Momentos teen (I)

Ese sentimiento adolescente…

Click here for the English version

Rebelde sin causa (Rebel Without a Cause, Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Sergi Sánchez

Es un gesto el que nos trae aquí, a aquella última noche, después de habitar una casa abandonada como si fuera un patio de juegos, un parque infantil, un planetario silencioso. La sensación de ser tres y no ser multitud, los tres pensando en ser únicos y especiales, en que no hay nada ni nadie que pueda compararse a ellos, y de repente el trío se rompe, unos disparos inútiles, el destino aplastando nuestras cabezas, James Dean gritando que él tiene las balas, y luego el gesto, esa chaqueta prestada, esa transferencia de destinos, y la delicadeza de Dean abrochándole la cremallera a Sal Mineo hasta el cuello, “siempre tenía frío”. No es solo la protección de los vivos hacia los muertos, o el romanticismo sublime del cine de Nicholas Ray, o el abrazo último de la fatalidad acallado por la ternura, o las palabras dolidas de una figura paterna despidiéndose de su amor platónico, o de su hijo adoptivo. Es la adolescencia en su estado más puro, con su lirismo violento y su intensidad atropellada, encarnados en la expresión de un afecto, el de la soledad acompañada que pronto se convertirá en la mochila llena de piedras que todos nos llevamos hacia la edad adulta, la expulsión de ese paraíso que ha sido infierno, la breve existencia de un ego que no encuentra espejo donde reconocerse.

El final de Rebelde sin causa esencializa el angst adolescente que recorrería todo el cine teenager —desde los drive-ins de los cincuenta hasta las comunas hippies de finales de los sesenta, para desembocar en el cine gamberro que John Hughes, y ahora la compañía itinerante de Judd Apatow, se han tomado más en serio—. En todas ellas hay algo que Éric Rohmer detectó en su bella crítica del filme de Ray (“Ajax ou le Cid?”, Cahiers du Cinéma, nº59): la circularidad de las emociones de la adolescencia, como la aguja de un tocadiscos que se niega a apartarse del mismo surco, siempre la misma canción, siempre la misma marea que nos devuelve la misma arena. La pureza equivocada de los sentimientos: el amor puro, el odio puro, la furia pura. Y luego la melancolía del rito de paso, que aquí se fragua en muerte de quien difícilmente podría haber superado su orfandad adolescente. Sal Mineo es, en cierto modo, como el Edmund de Alemania, año cero (Germania anno zero, Roberto Rossellini, 1948): después de pasearse por las ruinas de la América del bienestar, es incapaz de sostener la mirada del mundo adulto. Y es entonces cuando en el gesto triste de James Dean se manifiesta la creación de un género de películas que entendió la adolescencia como una enfermedad del alma que tenía remedio, que deseaba mirar hacia el futuro. Solo teníamos que saber abrigar al chico que fuimos.

© Sergi Sánchez, enero 2013

Aquel excitante curso (Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Amy Heckerling, 1982)

Girish Shambu

Las mejores teen movies dramatizan cierto flujo —la búsqueda y la lucha por una identidad— que está en el corazón de la experiencia adolescente. Pero para encontrar o formar la propia identidad en esta etapa, fluida y volátil, de la vida humana, uno debe tomar riesgos, aventurarse a nuevas experiencias. Las nuevas experiencias nos traen conocimiento: sobre nosotros mismos, sobre los otros, y sobre la cultura. Por lo tanto, la vida adolescente se construye, con frecuencia, sobre la adquisición ansiosa de conocimiento a través de la experiencia.

Para mí, esta doble cualidad que deja su marca en la adolescencia —la ansiedad y el aprendizaje, en realidad: la ansiedad por aprender— es cristalizada en un gran momento de Aquel excitante curso: cuando Stacy (Jennifer Jason Leigh) pierde su virginidad.

Stacy está impaciente por entrar en el mundo de la experiencia sexual, pero su impaciencia no brota de un deseo por experimentar placer. En lugar de eso, lo que ella quiere es aliviar la ansiedad que sufre pues cree que está llegando tarde a la adquisición de ese importante aprendizaje sexual que su amiga ya posee. En la cafetería, Stacy le dice a su mejor amiga (Phoebe Cates) que le preocupa que todas esa chicas con look a lo Pat Benatar (¡hay tres en su instituto!) despierten una atracción sexual de la que ella carece. Cuando confiesa su inocencia en temas sexuales, Linda le pregunta incrédulamente: “¿Nunca has dado una mamada? ¿Nunca? Stace, es fácil. No tiene nada de complicado.” Linda y Stacy se convierten en profesora y alumna por un momento y empiezan una demostración práctica usando dos zanahorias del mismo tamaño, lo cual mantiene entretenidos a un grupo de chicos que las observa desde una mesa vecina.

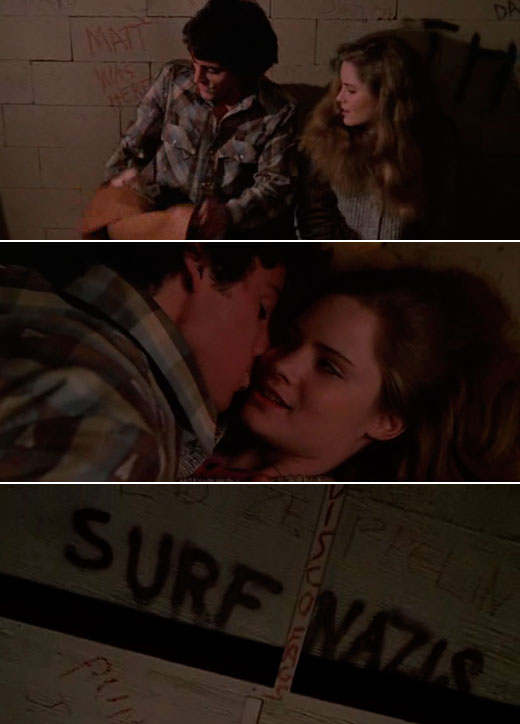

Stacy tiene solo 15 años, pero en su cita con un chico de 26 que se dedica a la venta de aparatos de música, miente y le deja creer que tiene 19. Él la recoge y la lleva a “The Point”, el dugout de un campo de béisbol, uno de esos lugares usados por las parejas para sobarse. Sin perder tiempo, él la besa y ambos se tumban en el incómodo y estrecho banco. En dos ocasiones vemos planos que corresponden a puntos de vista; pero la cámara apenas está interesada en el chico y, durante esta escena, se concentra sobre todo en el personaje de Stacy y en lo que ella ve: el techo mugriento, pintarrajeado con garabatos —grafitis que rezan cosas como “Disco Sucks” o “Surf Nazis”— e iluminado por una única luz de aspecto industrial. El chico se corre enseguida. Los ojos de Stacy permanecen abiertos casi todo el tiempo y hay en ellos una mirada de concentración y confusión (¡como si estuviese leyendo un libro muy complejo!). En la banda sonora escuchamos Somebody’s Baby de Jackson Browne, una canción sobre el anhelo adolescente usada de forma irónica.

Cuando esta escena abrupta y llena de brío concluye, lo que nos queda es la sensación de la brecha abierta en la mente de Stacy: entre la imagen del sexo que debe haber retenido en su cabeza durante largo tiempo (construida por las películas, la televisión, los amigos, en resumen: la cultura), y su experiencia concreta y real de esto en un espacio (banal) y en un tiempo (abreviado). Es mérito de la película el no entretenerse nunca, el no subrayar ni sentimentalizar jamás esta brecha en la que reside el conocimiento. Se trata, simplemente, del lugar para otra lección más de la vida adolescente; el filme pasará rápidamente a la siguiente.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

© Girish Shambu, enero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

L’âge atomique (Hélena Klotz, 2012)

Daniel de Partearroyo

La noche tiene su propia experiencia de temporalidad; sobre todo si eres joven. Si, además, a tu adolescencia le ha tocado en suerte la periferia de una gran ciudad para desarrollarse, los trayectos nocturnos de ida y vuelta a la almendra de sueños, discotecas y alcohol en busca de diversión terminan por formar un cúmulo de puntos muertos que acabas asumiendo tan inherente al devenir noctámbulo como la garganta cascada del día siguiente. La semana discurre entre clases absurdas y bancos de parque aburridos; el viernes, la ciudad abre sus calles, sus labios de neón, y ofrece el néctar de la Fiesta. Quedar con los amigos para coger el tren, bromear, mandar SMSes de última hora o repasar el maquillaje, beber en el vagón (las copas en los garitos son prohibitivas), hablar sobre los Stone Roses, trazar juntos los planes, expectativas e ilusiones de la noche. Un puñado de (demasiadas) horas más tarde, el camino se hará a la inversa: las ilusiones habrán sido reemplazadas por cansancio, las expectativas por decepciones, los planes por propósitos y la bebida por el último cigarrillo del paquete, ese que desearías compartir con una chica misteriosa de labios carnosos y nombre remoto, de declinación latina.

En L’âge atomique, Héléna Klotz dedica la mayor parte de su película a los trayectos que comparten Victor (Eliott Paquet) y Rainer (Dominik Wojcik); pequeños barcos que se hunden en el mar inmenso de una ciudad claustrofóbica, dice el último. Los dos tránsitos de la película quedan privilegiados como el tiempo de afianzamiento de la amistad: el de ida enmarca el regalo del pañuelo, en el de vuelta uno decide acompañar al otro en vez de iniciar su propia historia de amour fou. A fin de cuentas, si la adolescencia es la Gran Etapa de Tránsito por definición, tiene sentido que algo importante cristalice en esos momentos aparentemente perdidos, donde el tiempo fluye de otra manera y, a la vuelta, la borrachera muta en confesionario compartido. Aparte de los beatíficos rostros de héroes y deidades grecolatinas que tiene todo aquel que sale en su película, lo que retrata Héléna Klotz es el vagabundeo de esos cuerpos que cada noche salen para acariciar la vida durante unas horas. Pero también sabe que, lejos de la épica de la pista de baile, la tribuna de la barra de bar o el ring de las colas de entrada al club de moda, la epopeya de las adolescencias de extrarradio en realidad se gesta esperando la llegada del último metro o haciendo tiempo hasta que sale el primer autobús de la mañana.

© Daniel de Partearroyo, enero 2013

El club de los cinco (The Breakfast Club, John Hughes, 1985)

Cristina Álvarez López

Pocos filmes se construyen, en la medida en que lo hace El club de los cinco, sobre un combate tan intenso de energías positivas y negativas. En él, cada palabra, cada gesto, trae consigo una respuesta encendida, una reacción de ira o de identificación, de compasión o de rechazo. Los personajes se arrastran por la cuerda floja de los afectos y se debaten constantemente entre estrategias de ataque y de defensa, entre la necesidad imperiosa de abrirse a los demás y la de refugiarse en su soledad. Esto es precisamente lo que está en juego cuando Allison (Ally Sheedy), tras vaciar su bolso frente a Andrew (Emilio Estevez) y Brian (Anthony Michael Hall), confiesa que si lleva tantas cosas encima es porque quizás algún día tenga que fugarse de casa.

Sin embargo, cuando Andrew trata de averiguar cúal es su problema, ella reacciona de forma violenta, volviendo la pregunta en contra de él. Su negativa a hablar hace que la escena sea habitada por el fantasma de lo que permanece oculto y se llene de una tensión malsana que se propaga con cada corte de montaje. Andrew insiste: “¿Es algo malo? ¿Realmente malo? ¿Son tus padres?”. Ella asiente. Durante su conversación el volumen de la banda sonora —más propia de un thriller o de un filme de ciencia ficción, que de una teen movie— crece, se expande; los planos y contraplanos se vuelven cada vez más cerrados, hasta concentrarse solo en los rostros de los actores. Cuando, finalmente, Andrew formula la gran pregunta —“¿Qué te hacen?”—, nosotros ya estamos preparados para escuchar algo terrible (¿abusos? ¿malos tratos?: apenas sabemos nada de este personaje, todo lo que vemos es el reflejo de un trauma cuyo origen no ha sido todavía localizado). La respuesta de Allison, sus tres únicas palabras, son las siguientes: “Ellos me ignoran”.

Por supuesto, esto es algo que ha estado ahí desde el principio, solo que no lo habíamos visto. En la primera escena del filme —la que nos muestra la llegada de los cinco protagonistas al instituto—, Alison baja del asiento trasero del automóvil y da un paso adelante para decir adiós a sus padres, pero el coche arranca a toda velocidad antes de que ella tenga tiempo de esbozar siquiera un gesto de despedida. El filme está lleno de detalles como este, que solo advertimos en un segundo visionado —lo cual no es extraño si tenemos en cuenta que una de las preocupaciones esenciales de El club de los cinco radica en devolver a la imagen todo lo que le ha sido sustraído tras haber sido reducida a una etiqueta, a una tipología, a un estereotipo—.

El genio de John Hughes está inextricablemente unido a su profunda comprensión de los problemas de la adolescencia. O, más exactamente, al modo en que ha sabido traducir estos problemas en cuestiones de medida, de peso, de proporciones. En su manera de filmar la confesión de Allison, en ese alargar y sembrar la escena de pausas, de tensión, de expectativas, hay algo de la dificultad que supone para su personaje el expresar un sentimiento tan simple y, a la vez, tan complejo. “Ellos me ignoran”: dar forma a estas tres palabras que contienen el núcleo de su constitución como sujeto y, después, empujarlas al exterior. Hughes se acerca con extrema delicadeza a este momento, calibra con enorme cuidado este secreto que, una vez dicho, puede parecer insignificante y, sin embargo, para Allison lo es todo.

© Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

Loca aventura (Happy Campers, Daniel Waters, 2001)

Toni Junyent

“You know, one day, they’ll find a cure for AIDS… but they’ll never find one for sex”

Siempre resulta tentador imaginar nuestra propia biografía como una serie de puntos de inflexión o escenas complicadas en las que pudimos obrar de otra manera. A Donald (Justin Long), el monitor nerd de Loca aventura, una chica le propuso una vez un paseo en barca. Él, sin saber muy bien por qué, dijo que no. Y aún le duele. Cuando uno de los niños a los que cuida en el campamento le cuenta que una chica le ha hecho una proposición similar y no sabe qué hacer, Donald le insta a que no actúe como él y acuda a la cita.

Hacia el final de la película, Donald tiene otra breve conversación con el mismo chico, que le da las gracias por haber pasado el mejor verano de su vida. Cuando el monitor se dispone a agradecerle el cumplido, el chico empieza a reírse, le señala y dice: “Oh, man, I just got you”. Era una broma, se lo tragó, igual que quienes distribuyeron Loca aventura en España se tragaron —o decidieron obviar— que el título original de la película era irónico, y por eso la titularon de una forma tan aleatoria. Daniel Waters debutaba tras la cámara el mismo año que David Wain, y ambos ajusticiaron con saña el cine de campamentos: mientras Wain, en Wet Hot American Summer (2001), lo hacía desde el humor absurdo, Waters entonaba un réquiem por la inocencia perdida que contenía algunas de las líneas de diálogo más amargas que se pueden escuchar en una comedia juvenil reciente. El director de Loca aventura no debería necesitar presentación: es el guionista de películas de culto como Escuela de jóvenes asesinos (Heathers, 1988).

En este 2012 que apenas acabamos de dejar, otro boy scout llamado Wes Anderson cerraría el círculo de los campamentos con Moonrise Kingdom, en la que Bruce Willis volvía a salvar el mundo. Esta vez salvaba el pequeño mundo de dos adolescentes que se aman y están dispuestos a morir por ello —igual que la Wendy (Dominique Swain) de la película de Daniel Waters pretende inmolarse bobamente ante Wichita (Brad Renfro: este está muerto de verdad, en paz descanse), su amor fracasado—. Ambos acaban empapados por una avalancha de condones de agua. Una secuencia, la de los condones, que es puro cine político.

También yo, una vez, le dije que no a una chica, una estudiante de publicidad que, de hecho, me gustaba. No era exactamente el mismo caso que el del chaval de la película, pero admitiré que esa fue la primera y la última vez que pude haber entrado en su mundo, y a veces sigo pensando que, de haberle hecho caso en aquel instante concreto, algo podría haber cambiado, ni que fuera ligeramente, en mi vida. Ella se hizo diseñadora y, antes de eso, me dijeron que salió en un anuncio televisivo de condones, aunque nunca llegué a comprobar si el dato era cierto.

© Toni Junyent, enero 2013

Nunca me han besado (Never Been Kissed, Raja Gosnell, 1999)

Adrian Martin

En Nunca me han besado tardamos solo noventa segundos en ir y volver al Infierno Teen. En películas protagonizadas por adultos que revisitan sus años adolescentes —construidas a partir de premisas narrativas relacionadas con personajes infiltrados o con recuerdos presentados en forma de flashback— unas pocas escenas cruciales tienden a condensar todo el género teen, desde su iconografía a sus usuales situaciones argumentales. Nunca me han besado acelera todavía más ese proceso.

Josie (Drew Barrymore) toca fondo cuando vuelve al instituto e intenta desesperadamente encajar en él. Tras una serie de experiencias particularmente terribles, se encierra en la cabina del baño y se deja caer en el suelo, su espalda contra la puerta. Al principio de estos noventa segundos, la cámara desciende en un plano grúa y gira en espiral hasta encuadrar a Josie en esta posición desoladora, mientras algunos elementos, inteligentemente reeditados, de la canción de Madonna Like a Prayer —un acorde sostenido por el coro y el órgano— cuelgan suspendidos en el aire. ¡Después comprobaremos que la letra de este tema también ha sido reordenada de manera muy expresiva!

Una hermosa fusión de imagen y música: durante un primer plano de Josie —y la sobreimpresión, al principio misteriosa, de un llamativo y ondulado tejido rosa— el tambor repica cuatro veces, entonces la canción llega con toda su fuerza, igual que la joven ‘Josie Grossie’. Ella va a ir al baile de graduación con Billy (Denny Kirkwood), un compañero de instituto, el chico con el que siempre ha fantaseado, y se abandona a una excitada ensoñación llena de sonrisas, bailes y piruetas. El director Raja Gosnell filma casi todo esto en un único plano maestro: Barrymore en modo geek-superfeliz, sin cortarse un pelo, totalmente entregada —de sus gestos danzarines y sus expresiones hiperfemeninas (“¡Salgo en un plis!”) a su elaborada ortodoncia—.

Sin embargo, al otro lado de la puerta, le espera el mayor de los traumas (el recuerdo del cual ha sido desencadenado por el dolor del día presente): los movimientos de Billy —cuyo cuerpo asoma por el techo descapotable de una limusina que se acerca a la cámara a velocidad constante— se intercalan con el plano de una Josie feliz que aguarda en el porche; esto crea una tensión instantánea que no presagia nada bueno. La cita secreta de Billy asciende del coche, se pone en pie junto a él —una pesadilla que se cierne sobre la visión de Josie—, y entonces, desde el punto de vista de la protagonista, vemos como unos huevos son arrojados en su dirección. Cuando el primer huevo alcanza su cabeza, la canción de Madonna se corta, justo en la reverberación de la palabra “sueño”; cuando el segundo huevo se desparrama por su vestido, ella comienza a sollozar en medio de un crudo silencio que dobla su aflicción. En su economía emocional, esto es puro Lubitsch: en mitad de una comedia como esta, los diez segundos de Barrymore en esa posición encorvada se sienten como una eternidad del más oscuro desespero.

Volvemos a escuchar el “hum” del coro antepuesto a la repetición de la frase “es como un sueño”. Después el tambor da comienzo al puente instrumental de la canción (en el que destaca un bajo, grave y pesado) y, en ese mismo instante, la imagen nos lleva, mediante un corte de montaje, a las piernas de Josie corriendo —pero este es un impresionante salto hacia adelante, hacia la Josie adulta con su disfraz de infiltrada—. Se suceden tres planos más de ella, en los que la vemos corriendo por el abarrotado pasillo de la escuela —otra aprehensión pesadillesca del espacio—; después Josie se golpea contra una puerta que se abre y cae inconsciente. De repente, estamos ante un momento de slapstick patoso que da lugar a un nuevo movimiento de la trama.

¡En estos noventa segundos tenemos infinitesimales giros y modulaciones del ánimo! Tontas, dulces, tensas, tristes, animadas, agudas, terroríficas, reflexivas y, finalmente, de vuelta a la ligereza: todo ello representado en acciones y estados físicos. ¡Qué cine tan glorioso nos ha dado el género teen!

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

© Adrian Martin, enero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

Ariane (Love in the Afternoon, Billy Wilder, 1957)

Albert Elduque

¿Qué puede contener el archivador de un padre? La mayoría de veces, documentos banales y papelotes sin interés. En el caso del detective privado Claude Chavasse (Maurice Chevalier), ese archivador esconde historias apasionadas, arrebatos amorosos, adulterios suicidas, todas aquellas sospechas de maridos y esposas que él ha tratado de verificar. Su hija, Ariane (Audrey Hepburn), pulcra estudiante de conservatorio, buena hija de su padre, y buena aprendiz, espía entre estos papeles, recortes de periódico y fotografías furtivas, aprendiéndose al dedillo todas sus truculencias, soñando en que algún día pueda protagonizarlas. Y, al mismo tiempo, escucha tras la puerta, soñando amoríos mientras el detective atiende a sus clientes. Lo que está al otro lado es fundamental, aprendió Wilder de Lubitsch. En este caso, las barreras de puertas y cajones demarcan la sordidez de la vida adulta, la que el detective ha escondido a Ariane durante toda su vida. Sin embargo, ella ve en estos umbrales los pasajes a locas historias de amor, y flirtea con ellos para vivir un romántico cuento de hadas con el playboy Frank Flannagan (Gary Cooper), al que conoce en un hotel, salvándolo de un disparo en medio de la noche.

Tras el primer encuentro, una memorable secuencia. La puerta divisoria delimitará ahora el refugio de la joven enamorada, y las historias del archivador pasarán a su atril para pisar las partituras de la Sinfonía 88 de Haydn, que toca en el violonchelo. No sabemos la edad exacta de Ariane, pero vemos aquí los secretos propios de la adolescencia: tras este biombo musical se acomodarán las fotografías y noticias sobre la disipada vida de Flannagan, que observa fascinada. Así, construye fantasías románticas con el rostro, mientras la ejecución musical la envuelve de una pátina de niña aplicada a los oídos de su padre, en el cuarto de al lado. Sin embargo, la mirada curiosa sobre las imágenes del playboy acabará dando al traste con su ensayo musical, y en la pieza clásica se colarán errores varios, los de una tímida rebelde llevada por la pasión: un temblar cosquilleante al ver a Flannagan rodeado de geishas, una nota torpe ante su rostro de hombre del año, y un frotar monótono y pasmado cuando descubre el intento de suicidio de una de sus amantes. Los papeles confidenciales se han convertido, ahora, en una nueva partitura, que dialoga eróticamente con su rostro y enciende desde dentro las notas de Haydn. Por mucho que Ariane esconda sus historias tras la puerta, el atril o sus coletas infantiles, los pentagramas amorosos saldrán a la superficie y la música terminará delatándola. En ese Haydn desajustado la chica interpreta su primera aventura amorosa.

© Albert Elduque, enero 2013

Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff, 2001)

Stephanie Van Schilt

Tras años creciendo juntas, Enid (Thora Birch) y su mejor amiga Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) están tratando se sobreponerse a la resaca del instituto y empiezan a alejarse la una de la otra. Recién graduadas, sus caminos han comenzado a divergir y seguimos a Enid mientras deambula por la América suburbana, ahogada por su malestar social.

Una incómoda encarnación de contradicciones defensivas. Enid, aunque llena de angustia, es sensible; es mordaz pero introspectiva, escéptica pero inconsciente. La mayor parte del tiempo, este personaje es monótono y parece carecer de emociones; hay una distancia entre ella y el mundo que cubierta con una incredulidad burlona y un anhelo triste y contenido. No es hasta más tarde cuando, tras una breve y fastidiosa guerra verbal con Rebecca, el filme nos muestra a Enid expresando una emoción de forma directa. Se lanza sobre la cama y llora entre los desperdicios de su vida. Esta efusión momentánea de aflicción nos demuestra su verdadera fragilidad y, si escuchamos con atención, podemos oír como algunas notas del tema principal de Ghost World, compuesto por David Kitay, se elevan ligeramente en la banda sonora. Esos acordes, sutilmente dolientes, permanecen colgados en el aire, en segundo plano, ofreciendo a Enid un abrazo dulce y empático.

La composición de Kitay surte un embrujo perfecto en Ghost World, puntuando el filme tanto en momentos muy personales de desespero y melancolía, como en otros de travesura y descubrimiento. Mientras deambula con Rebecca y Seymour (Steve Buscemi), o durante un paseo dedicado a la contemplación solitaria, el tema principal de Ghost World acompaña a Enid, desencadenando un sentimiento de emoción que no deja de martillear en mi corazón con cada nuevo visionado.

El concepto de alienación y las teen movies van de la mano; representar ese extraño sentimiento de desplazamiento, confuso y aislado, que uno siente durante esos tumultuosos años adolescentes es inevitable y necesario. La alienación forma y da forma al universo de Ghost World —todo lo que Enid experimenta orbita alrededor de este sentimiento, pero, al mismo tiempo, esto es expresado de manera sutil por la película—.

Mientras Enid se mueve por su mundo, dejando atrás los rostros de gente corriente iluminados por los neones de las tiendas o al hombre solitario que espera en una difunta parada de autobús, el tema de Kitay acompaña sus pasos sin objetivo; sus pesadas botas marchan al ritmo del delicado latido que colma de sentimiento a la secuencia. El uso de esta pieza resuena suavemente revelando la emoción, dando voz —implícitamente— al sentimiento de desplazamiento interno y externo de Enid, y conjurando su tristeza egocéntrica que viene de cometer errores y, aún así, no encontrar un lugar en el mundo.

Al final del filme escucharemos el tema en su totalidad, que llega al crescendo en el momento en que ella se sube a un autobús en dirección desconocida. En ese instante, mientras el tema crece en una paz y unas pausas perfectas, el aire se llena de temor y de esperanza, de sabiduría y de misterio: el sonido de Kitay se eleva para acentuar el modo en que ese terco aislamiento, con frecuencia autoinfligido, se mezcla con un potente (y paradójico) sentimiento de necesidad y de deseo insatisfecho que, para alguien como Enid, es demasiado difícil articular. Cómo, con nuestra actitud frustrada y los dientes apretados, nos balanceamos en el límite de la razón hasta que, con el tiempo, por fin comprendemos que no somos los únicos en sentirnos así, pero a veces necesitamos estar solos.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

© Stephanie Van Schilt, enero 2013. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2013

Polo de limón (Eskimo Limon, Boaz Davidson, 1978) / El último americano virgen (The Last American Virgin, Boaz Davidson, 1982)

Pablo Vázquez

No existen apenas diferencias de peso entre el original Polo de limón y el remake El último americano virgen, salvo el previsible cambio de reparto y escenario, la banda sonora y la introducción —en la segunda— de la cocaína. Ambas fueron dirigidas por Boaz Davidson: la primera fue un éxito en Israel y llegó a representar a su país en el Festival de Berlín; la segunda, poco más que un título a engrosar la catarata de filmes juveniles que facturaba Estados Unidos por entonces, si bien en su vertiente más realista, con cierto aura de sexploitation que la acercaba más a títulos de bajo presupuesto como La pornopalla (The Cheerleaders, Paul Glicker, 1973) o H.O.T.S. (Gerald Seth Sindell, 1979) que a los más recordados éxitos de John Landis, Ivan Reitman o Bob Clark. Toda esta introducción viene a cuento porque “mi momento teen” realmente son dos, repetidos y superpuestos. Un par de desenlaces fotocopiados en los que no cabe atisbo de redención o esperanza: la tristeza de Gary (Lawrence Monoson), traspasando la pantalla y sobrevolando un ejército de rechazos reconocibles, y la decepción final de Benji (Yftach Katzur) —en la original—, reflejo de carencias e incomodidades propias.

Son estas películas sobre el dolor parejo a las primeras veces, aproximaciones a unos claroscuros que la mayoría de los realizadores de cine juvenil, quizás por demasiado familiares, prefieren obviar o dulcificar. Ese tipo de historias en las que uno, al revisitarlas, no pierde la esperanza de que acaben de forma diferente, y de que sus protagonistas corran mejor suerte, como si las narraciones no quedaran grabadas en alguna parte y renacieran con cada nuevo acercamiento. Porque en ambos casos, cuando se descubre el pastel —que aquí no desvelaremos— y el protagonista se viene abajo, cuando vemos que la película acaba (suena la música, corre el rodillo) y que las cosas no habrá Dios ni guionista que las arregle, nos damos cuenta de que todo lo anterior —las promesas de sexo festivo, la amistad, el poder del amor: temas claves de la teen comedy— no era más que la sombra de un engaño multimedia, una patraña llamada a aligerar la contundencia del mazazo. Benji / Gary se desploma y acepta su condición de loser atrapado en una parodia pagafántica de educación sentimental: su gesto le guiña un ojo a Fitzgerald (Al otro lado del Paraíso), a Salinger (El guardián entre el centeno) y a Musil (Las tribulaciones del estudiante Törless) y, por descontado, también a Truffaut y a Malle, anticipando, de paso, las futuras aproximaciones de autores tan diferentes como Harmony Korine, Richard Linklater, Gregg Araki, Wes Anderson o David Trueba, autores afines a un sentimiento trágico de lo adolescente, que no excluye el coqueteo con el masoquismo, la misantropía o la frustración sexual. No se me ocurre una mayor bofetada contra el espectador convencional de comedias juveniles presuntamente sexuales que concluir una odisea sobre el desvirgamiento con la idea de que el sexo es, la mayoría de las veces, el mayor y más cruel de los demonios.

© Pablo Vázquez, enero 2013

That teenage feeling …

Click aquí para la versión en español

Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Sergi Sánchez

It is a gesture that brings us here, to this final night, after inhabiting an empty house (as if it were a play pen), a kids’ park, and a silent planetarium. There is a feeling of being a threesome – not a multitude – all three believing they are unique and special, because nothing or no one can truly compare to them … When suddenly, the trio is broken, one of them dies uselessly, destiny crashes down on their heads, James Dean screams that was he who had the bullets – and then the gesture, this red jacket that was loaned, destinies switched, and the delicacy of Dean fixing Sal Mineo’s zipper all the way to the neck, because “He was always cold”. This is not only the living’s care for the dead; or the sublime romanticism of Nicholas Ray’s cinema; or the last kiss of fate smoothed by an act of tenderness; or the grieving words of a father-figure in his parting gesture for his Platonic lover or adopted son. Rather, it is adolescence in its purest state, with its violent lyricism and its propelled intensity, embodied in the expression of an affect, and of the accompanying loneliness that is quickly converted into that sack of heavy rocks which all of us must drag into adulthood – the explusion from that Heaven which has been Hell, the brief existence of an ego that is unable to find the mirror in which to recognise itself.

The final scene of Rebel Without a Cause essentialises the adolescent angst that informs all teen cinema – from the drive-ins of the 1950s and the hippie communes of the late ‘60s, to the light-hearted movies of John Hughes and the contemporary travelling players of Judd Apatow, who take this material more seriously. In all these, there is something that Éric Rohmer once detected, in his beautiful 1956 review of Ray’s film (‘Ajax or the Cid?’, in Jim Hillier (ed.), Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 111-117): the circularity of adolescent emotions, like the gramophone needle that refuses to get out of the one groove – always the same old song, always the same surge that deposits us back in the same ring. The equivocating purity of the emotions: pure love, pure hate, pure rage. And then the melancholia of the rite of passage, forged here in the death of the person who faced the utmost difficulty in surpassing his teenage orphan-status. Mineo is, in a certain way, like the Edmund of Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero (1948): after wandering among the ruins of a well-off America, he is incapable of sustaining the gaze of the adult world. And when Dean’s sad gesture inaugurates a film genre that grasps adolescence as a soul sickness, it is then that a remedy appears, a desire to look to the future. We only have to know how to shelter the boy whom we once were.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Sergi Sánchez January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (Amy Heckerling, 1982)

Girish Shambu

The best teen films dramatise a certain flux – a search and struggle for an identity – that is at the heart of adolescent experience. But in order to ‘find’ or form one’s identity at this fluid and volatile stage of human life, one must take risks, venture into new experiences. New experiences bring us knowledge: about oneself, about others, and about culture. Thus, teenage life is frequently about the anxious acquisition of knowledge through experience.

For me, this double quality that marks adolescence – anxiety and learning, in fact, an anxiety about learning – is crystallised in a great moment from Fast Times at Ridgemont High: when Stacy (Jennifer Jason Leigh) loses her virginity.

Stacy is eager to enter the world of sexual experience, but her eagerness doesn’t spring from a desire to experience pleasure. Instead, she wants to unburden herself of the anxiety she suffers because she thinks she is late in acquiring the important sexual knowledge that her friends possess. In the cafeteria, she worries to her best friend Linda (Phoebe Cates) about all the Pat Benatar look-alikes in her school (there are three of them!) being more sexually appealing than she is. When she confesses her sexual innocence, Linda asks incredulously: “You’ve never given a blow job? Never? Stace, it’s easy. There’s nothing to it.” Linda and Stacy become teacher and student for a moment, going through a practical demonstration using matching carrots, much to the amusement of a table of boys in the vicinity.

Stacy is just 15 years old, but she lies to her date, a 26-year-old stereo salesman, giving him the impression she is 19. He picks her up and they drive to “The Point,” a makeout spot in a baseball dugout. Wasting no time, he kisses her and they uncomfortably stretch out on the narrow bench. Twice we see POV shots; but the camera is scarcely interested in the guy – it primarily looks at and with Stacy during this scene. She sees the grimy ceiling, defaced with graffiti scrawls (“Disco Sucks”; “Surf Nazis”) illuminated by a single industrial-looking light. The guy comes – hurriedly. Stacy’s eyes remain open nearly all the while, and there is a look of concentration and puzzlement in them – as if she were reading a challenging book! On the soundtrack is Jackson Browne’s ironically used song of teenage yearning, “Somebody’s Baby”.

What remains after this brisk scene has passed is our sense of the gap in Stacy’s mind: between the image of sex she must have long held in her head (constructed by movies, TV, friends – in short, culture) and her concrete, real experience of it in (banal) space and (abbreviated) time. It is to the film’s credit that this gap – in which lies knowledge – is never lingered upon, never italicised or sentimentalised. It is simply the site of one more lesson of teenage life; the film quickly moves on to the next.

© Girish Shambu January 2013

L’âge atomique (Hélena Klotz, 2012)

Daniel de Partearroyo

The night holds its own, particular experience of temporality – especially if you’re young. And if, as well, it was your particular fortune to have your adolescence unfold on the periphery of a large city, then the nightly, round-trip journeys to the well of dreams, discos and booze, in search of good times, will end up forming a cluster of dead moments – which you must assume as inherent to this business of being a night owl, just like the shocking sore throat you will nurse the next day. The weekdays alternate between ridiculous classes and boredom on park benches; but on Friday, the city opens its streets, its lips of neon, to offer the Feast’s nectar. Get together with your friends to catch the train, joke, send last-minute SMS messages or check your make-up; drink in the car (the cost of a glass in these joints is so expensive), chat about the Stone Roses, make plans together, share the night’s hopes and dreams. A bunch of (too many) hours later, and the path is reversed: dreams have been replaced by fatigue, hope by disappointment, plans by consequences, and alcohol by the last cigarette in the pack – which you would like to be sharing with a girl who has full lips and an obscure name of Latin origin.

In L’âge atomique, Héléna Klotz devotes most of the film to the journeys shared by Victor (Eliott Paquet) and Rainer (Dominik Wojcik) – small boats sinking in the vast sea of a claustrophobic city, as the latter says. The two trips shown by the film are privileged as a time of the consolidation of friendship: the ‘going’ marked by the gift of a handkerchief; and the returning, when one decides to stay with the other rather than pursuing his own tale of amour fou. At the end of the day, if the teen age is (by definition) the Great Transitional Stage, it makes perfect sense that something significant crystallises in these seemingly oblivious moments, in which time flows differently, and – on the return trip – drunkenness morphs into an intimate confession. Beyond the angelic faces (like mythic heroes or Greco-Latin gods) on everybody who parades in this film, what Klotz really portrays here is the vagabond nature of these bodies that, each night, come to cherish life for a few, precious hours. But she also knows that – away from the drama of the dance floor, the tribunal at the bar or the gauntlet of queuing for entrance to a trendy club – this saga of suburban teens is, in reality, the gesture of waiting for last train to arrive, or killing time before the first bus of the morning.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Daniel de Partearroyo January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

The Breakfast Club (John Hughes, 1985)

Cristina Álvarez López

Few films are constructed on such an intense struggle of positive and negative energies as is The Breakfast Club. Every word, every gesture in it solicits a fiery response: a reaction of rage or identification, compassion or rejection. The characters run the gauntlet of emotions, constantly torn between strategies of attack or defence, between the urgent need to open up to others or take refuge in solitude. This is precisely what is at stake when Allison (Ally Sheedy), after emptying her bag in front of Andrew (Emilio Estevez) and Brian (Anthony Michael Hall), confesses that the reason she carries so many things is that, maybe someday, she will have to leave home in a hurry.

However, when Andrew approaches Allison to find out what her problem is, she reacts violently, turning the question against him. Her refusal to answer fills the scene with the aura of what remains hidden, and instils a malignant tension that grows with each cut in the découpage. Andrew insists: ‘Is it something bad? Really bad? Your parents?’ She nods assent. During their dialogue, the volume level of the soundtrack – more akin to a thriller or science fiction film than a teen movie – keeps growing, filling out; the shots and reverse-shots close in so as to concentrate solely on the actors’ faces.

By the time Andrew finally asks the Big Question – ‘What do they do to you?’ – we are ready to hear something terrible (abuse? maltreatment? – since we really know nothing about this character, all we can discern are the signs of some trauma whose origin is untraceable). Allison’s reply, her three little words, run as follows: ‘They ignore me’.

Of course, this is something that has been there from the start; we just did not see it. In the film’s opening scene – showing the five principal characters arriving at school – Allison emerges from the back of a car and steps forward to say goodbye to her parents. But the vehicle takes off full throttle before she has time to even begin her farewell gesture. The film is full of details just like this, which we only catch on a second viewing: not so strange, when we consider that one of the essential concerns of The Breakfast Club involves giving back to an image everything that has been subtracted from it once it has been reduced to a label, a typology, a stereotype …

The genius of John Hughes is inextricably tied to his profound understanding of the problems of adolescence. Or, more precisely, the way he is able to translate these problems into issues of measure, weight and proportion. In the way he films Allison’s confession, the way he stretches out and laces the scene with pauses, tension, expectations: in this, there is something of the difficulty experienced by the character in expressing a feeling that is at once so simple and so complex: ‘They ignore me’. To give form to these three words which crystallise her constitution as a subject – and then, to get beyond them.

Hughes approaches this moment with extreme delicacy; with enormous care, he calibrates this secret that, once said, may seem insignificant – but which, for Allison, is everything.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Cristina Álvarez López January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

Happy Campers (Daniel Waters, 2001)

Toni Junyent

“You know, one day, they’ll find a cure for AIDS … but they’ll never find one for sex.”

It’s always tempting to imagine our own life story as a series of turning points or complicated scenes which could not possibly have happened any other way. A girl once proposed a boat trip to Donald (Justin Long), the nerdy monitor in Happy Campers. Without really knowing why, he says no. And it still hurts. When one of the kids he is minding at camp tells him that a girl has made a similar proposition to him and that he doesn’t know what to do, Donald urges the boy to not do what he did, but to go through with the rendezvous.

Towards the end of the movie, Donald has another, brief conversation with the same boy, who thanks him for the experiencing the best summer of his life. When the monitor begins to thank him for the compliment, the kid starts laughing, points at him and exclaims: ‘Oh man, I just got you!’ It was just a joke, and Donald swallowed it – just like the Spanish distributors who were the victims (or the wilful ignorers) of the irony contained in the original title Happy Campers, translating it aribitrarily as ‘crazy adventure’ (Loca aventura).

Daniel Waters debuted behind the camera the same year as David Wain, and both will viciously execute the cinema of campers: while Wain did it with a sense of the absurd in Wet Hot American Summer (2001), Waters fashions a requiem for lost innocence, devising some of the bitterest lines of dialogue to be heard in recent youth comedy. The director of Happy Campers needs no introduction: he is the writer of cult films including Heathers (1988).

In this past year of 2012 which is barely over, we have another boy scout, Wes Anderson, to close the camping circle with Moonrise Kingdom – in which Bruce Willis returns to save the world. This time, he saves the tiny world of the two adolescents who are in love, and willing to die for it – just as Wendy (Dominique Swain) in Waters’ movie foolishly intends to sacrifice herself for Wichita (Brad Renfro – who is really dead, RIP), her failed love. Both of them end up drenched in an avalanche of water-filled condoms. And this condom scene is pure political cinema.

And me, too: I once said no to a girl – an advertising student who, indeed, I was fond of. It wasn’t quite the same as for the kid in the film, but I will admit that it was the first and last time I could have entered such a world. I stilll sometimes think that, if I had made this decision at this precise moment, something might have changed – even if only slightly – in my life. She became a designer and, before that, or so I heard, her career stepping-stone was a TV commercial for condoms. But I’ve never been able to verify the truth of that rumour.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Toni Junyent January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

Never Been Kissed (Raja Gosnell, 1999)

Adrian Martin

It takes ninety seconds to go to Teen Hell and to come back in Never Been Kissed. In films where adult characters revisit their adolescent years – through undercover narrative premises or flashback memories – a few crucial scenes tend to condense the entire teen genre, its iconography and familiar plot situations. Never Been Kissed speeds up this process even more.

Josie (Drew Barrymore) hits rock bottom in her hopeless attempt to fit back into High School; after a round of especially awful experiences, she shuts herself into a toilet cubicle and sits, despondent on the floor, her back against the door. At the beginning of this ninety seconds, a crane shot spirals down to frame Josie in this sad position, as cleverly re-edited elements from Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” (held organ chord and choir) – with expressively reshuffled lyrics! – hang suspended in the air.

A beautiful fusion of image and music: during a close-up of Josie – and the at-first mysterious superimposition of swirling, garish, pink fabric – the snare drum in the song hits four times, the song gets into full swing, and so does the young ‘Josie Grossie’. She’s got a date for the Prom with her dream boy from school, Billy (Denny Kirkwood), and she is lost in an excited smiling-dancing-twirling reverie, caught mainly in a master shot by director Raja Gosnell: Barrymore in full-out blissful-geek mode, from her bopping gestures and girly patter (“I’ll be out in a jiffer!”) to her elaborate dental work.

Just outside the front door, however, lies the greater trauma, the memory of which has been triggered by the modern-day grief: the intercut movements of Billy, standing, approaching the panning camera at cruise-speed in a limo, and a track into happy Josie on the porch, create an instantly ominous tension. Billy’s secret date ascends from the car alongside Billy – a nightmare in Josie’s vision – and eggs are hurled right into her POV spot. As the first egg hits her face, the soundtrack cuts Madonna on the reverb of the word “dream”; as the second hits her dress, she sobs in stark silence, bent over in distress. It’s sheer Lubitsch in its emotional economy: ten seconds in this hunched position, in the middle of a comedy like this, feels like an eternity of the darkest despair.

The choir-hum returns, with a reprise of “It’s like a dream”, then the snare drum, this time kicking off the ‘heavy bass’ instrumental bridge of the song, cut exactly to Josie’s running legs – but this is a breathtaking leap forward, to the adult-Josie-in-disguise. Three more shots of her running down the crowded school corridor – another nightmarish apprehension of space – then Josie is knocked unconscious by an opening door. Suddenly it’s a goofy slapstick moment, and a new plot move begins.

So many split-second switches and modulations of mood in this ninety seconds! Silly, sweet, tense, sad, rousing, sharp, horrific, reflective, and finally back to lightweight: all played out in physical actions and states. What glorious cinema the teen genre has given us!

© Adrian Martin November 2012

Love in the Afternoon (Billy Wilder, 1957)

Albert Elduque

What might a parent’s filing cabinet contain? Mainly just banal documents, papers of no interest whatsoever. But in the case of Private Detective Claude Chavasse (Maurice Chevalier), this cabinet conceals impassioned tales, lovers’ quarrels, suicides resulting from infidelities – everything suspected of certain husbands and wives whom he has been hired to investigate. His daughter, Ariane (Audrey Hepburn) – diligent music student at the Conservatory, obedient child and fine apprentice –ferrets around in her father’s papers, news clippings and spy photos. She figures out all the juicy stuff they hint at – and hopes, one day, to be a star player in such drama. Meanwhile, she also listens behind her father’s door: imagining all these love affairs, while the Private Detective attends to his customers. As Wilder learnt from Lubitsch: whatever is on the other side of a door is the most essential thing. In this instance, the barriers constituted by doors and drawers mark off the sordidness of the adult world – exactly what the Detective has hidden from Ariane her whole life. She, however, sees in these ‘openings’ the pathway to lands of amour fou, and entertains the notion of living out a romantic fairy tale with playboy Frank Flannagan (Gary Cooper), whom she meets in a hotel room – saving him from getting shot in the middle of the night.

There is a memorable scene after their first encounter. The dividing door now marks out a refuge for the amorous young girl, and those stories in the filing cabinet pass to her music stand, dotting the score of Haydn’s 88th Symphony, which she plays on the cello. We don’t know Ariane’s precise age, but here we witness those secrets befitting adolescence: this musical prop holds photos and news stories concerning Flannagan’s life of dissipation, that she follows with fascination. This is how she builds her romantic fantasies, with images of his face, while her musical accompaniment swathes him in a childlike aura – reaching her father’s ears in the adjacent room. However, this absorbed gaze upon the playboy’s images ends up interfering with her music rehearsal, resulting in several, distracted mistakes, made by a shy rebel inflamed by passion: a ticklish tremolo upon seeing Flannagan surrounded by geishas; a flubbed note as she views his face on Confidential magazine cover as ‘Man of the Year’; a stunned, monotonous, held string when she discovers that one of his mistresses attempted suicide. These confidential files have now become a new musical score, in erotic dialogue with her face, illuminated from within by Haydn’s music. No matter how much Ariane tries to hide these items behind the door, the lectern, or her childish pigtails, those amorous staves will nonetheless rise to the surface, and the music will betray it. In this wonky Haydn, the girl performs her first adventure in love.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Albert Elduque January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013

Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff, 2001)

Stephanie Van Schilt

After years of growing up together, best friends Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) are wading through their high school hangovers and starting to grow apart. Fresh from graduation, their paths begin to diverge and we follow Enid as she meanders through suburban American, weighed down by her societal malaise.

An uneasy embodiment of defensive contradiction, Enid is angst-ridden yet sensitive, snarky yet introspective, skeptical yet unaware. For the most part, Enid is monotone and seemingly emotionless; there is a distance between her and the world that is filled with derisive disbelief and understated, forlorn longing. It’s not until late in the film, after a brief and stubborn war of words with Rebecca, that Enid is shown directly expressing emotion. Collapsing on her bed, she sobs amongst the detritus of her life. It is a short outpouring of grief that demonstrates her true fragility, and if you listen closely, you can hear a few notes from David Kitay’s ‘Ghost World Main Theme’ hover lightly on the air. Subtly aching in the background, the notes quietly linger, offering Enid a gentle, empathetic embrace.

Kitay’s composition perfectly haunts Ghost World, punctuating the film at such points of personal despair and melancholy, as well as moments of mischief and discovery. Whether wandering with Rebecca or Seymour (Steve Bucemi), or during a solitary walk of lonely contemplation, ‘Ghost World Main Theme’ accompanies Enid, attributing a sense of emotion that hammers through my heart upon each viewing

The concept of alienation and teen films go hand-in-hand; depicting the awkward sense of confused and isolated displacement one feels during those tumultuous adolescent years is inevitable and necessary. Alienation blatantly forms and informs Ghost World’s universe – everything that Enid experiences orbits around this feeling – but, similarly, it is also conveyed with subtlety.

As Enid moves through her world, past the neon glow of average shop faces or the solitary man waiting at a defunct bus stop, Kitay’s theme accompanies her detached steps; her plodding boots march in time to the delicate beat that fills the sequence with feeling. The use of this piece resonates delicately to reveal the emotionality, implicitly giving voice to Enid’s internal and external sense of displacement, conjuring the self-involved sadness that comes from making mistakes and not yet belonging.

At the end of the film, the piece is played at length, coming to a crescendo as she hops on a bus toward an unknown destination. In that moment, as the theme builds with perfect pauses and pace, the air is filled with dread and hope, wisdom and mystery: Kitay’s sound stands to accentuate how stubborn isolation, often self-inflicted, mixes with a potent (and paradoxical) sense of neediness and longing that is too difficult for someone like Enid to articulate. How, with a frustrated stance and clenched jaw, we teeter on the edge of reason until you come to realise, with time, that you’re not alone in feeling that way, but sometimes you need to be on your own.

© Stephanie Van Schilt January 2013

Lemon Popsicle (Eskimo Limon, Boaz Davidson, 1978) / The Last American Virgin (Boaz Davidson, 1982)

Pablo Vázquez

There is no significant difference between the original Lemon Popsicle and its remake, The Last American Virgin – apart from the obvious changes in cast and script and soundtrack, and the introduction (in the latter) of cocaine. Both were directed by Boaz Davidson. The former was a huge popular success in Israel and represented the nation at the Berlin Film Festival; while the latter was merely one more title to swell the tidal wave of youth-oriented fims that had flooded the United States by then, although with a more realistic side to it – and certainly with a sexploitation aura that aligns it more with such low-budget flicks as The Cheerleaders (Paul Glicker, 1973) and H.O.T.S. (Seth Gerald Sindell, 1979) than with better-remembered hits by John Landis, Ian Reitman or Bob Clark. This entire introduction is to set up the fact that my teen moment is really two, repeated and superimposed: a pair of endings, one a photocopy of the other, that give no glimpse of hope or redemption – the misery of Gary (Lawrence Monoson in Last American Virgin), overflowing the screen and illuminating a legion of familiar rejections; and the ultimate disappointment of Benji (Yftach Katzur in Lemon Popsicle), a reflection of my own limitations and discomforts.

These are movies about the pain associated with the ‘first times’, approximations of those shades of chiaroscuro that – perhaps because they are all too familiar – most filmmakers of youth prefer to ignore, or sweeten. The kind of stories that, when we revisit them, we still cannot but hope that they will end up differently, that the characters will have better luck this time – as if they were not actually already stored somewhere, and could be reborn at each go-around. Since, in both cases, ‘when the pie is opened’ (no spoilers here) and the hero falls down, when we realise that it is truly the end (music plays, credits roll) – and that there is neither God nor screenwriter to rearrange events – it is then that we grasp that all which has gone before (the promises of pleasurable sex, friendship, love’s power: in other words, all the key teen movie themes) amounts to nothing more than the trace of a multimedia hoax … a tall tale to ameliorate the force of the blow. Benji/Gary collapses and accepts his status as loser, stuck inside the nice-guy-comes-last parody of a sentimental education: his gesture is a nod to F. Scott Fitzgerald (This Side of Paradise), J.D. Salinger (Catcher in the Rye) and Robert Musil (The Confusions of Young Törless), as well as, of course, François Truffaut and Louis Malle – also anticipating, by the way, future approximations by auteurs as diverse as Harmony Korine, Richard Linklater, Gregg Araki, Wes Anderson and David Trueba … all of them artists connected to a tragic sense of adolescence, which does not exclude flirtation with masochism, misanthropy and sexual frustration. I cannot think of a finer slap to the face of the ‘normal’ viewer of youth films – presumed to be sex comedies – than this conclusion to a journey of loss-of-virginity: the revelation that sex is, most of the time, the greatest and cruelest of all demons.

Translated by Adrian Martin

© Pablo Vázquez January 2013. English translation © Adrian Martin January 2013