Philippe Garrel: Retratos

Retratos

Click here for the English version

I. Eye to Eye

¿Dónde reside el misterio de esas imágenes que te golpean la primera vez que las ves y cuya huella te persigue toda la vida? Hay una escena en El nacimiento del amor (La naissance de l’amour, Philippe Garrel, 1993) cuyo fulgor inflamó de una manera salvaje algo que no tenía, todavía, nombre o explicación. Más que una escena, es un fragmento de tiempo sostenido: un plano/contraplano, de casi un minuto de duración, donde un hombre y una mujer se reencuentran, tras haber estado separados durante largo tiempo, y se miran a los ojos. Está emplazada casi al final del filme, cuando Paul (Lou Castel) y Marcus (Jean-Pierre Léaud), los dos amigos protagonistas, viajan desde París hasta Roma en busca de la esposa del segundo, Hélène (Dominique Reymond), que le abandonó por otro hombre. Una vez allí, él la llama por teléfono y ella, quizás inesperadamente, le dice: “Ven”.

Se trata de un momento que se había extendido en mi recuerdo ganándose un espacio mayor al que realmente ocupa en el metraje del filme. Esto se debe, sin duda, a que en esos dos primeros planos de los rostros de la pareja podemos sentir cómo se concentra algo. Son planos cargados, graves y, al mismo tiempo, intensos. Pero esa carga, esa gravedad, esa intensidad… ¿De dónde vienen? ¿Cómo pueden dos imágenes crear tal afecto e instalarse en un rincón secreto de la memoria para regresar intermitentemente a lo largo de los años, insistentes y sobreexpuestas, como los fantasmas en los filmes de Garrel?

Hay, en el modo de abordar esta escena, algo muy minimalista y, a la vez, extraordinariamente poderoso. Un primer plano, blanco y luminoso, de Dominique Reymond: 8 segundos de silencio total dedicados a romper una barrera, a filmar el nacimiento de la sonrisa que, con dificultad, se va esbozando en su rostro. Y después el contraplano, fuertemente contrastado, de Jean-Pierre Léaud, sostenido –casi dolorosamente- durante 50 segundos. Es el trabajo con la duración y el primer plano -una de las grandes potencias del cine de Garrel- lo que dota a esta escena de su gravedad. Es la tensión que sacude al arte del retrato cuando este se enfrenta al latido del tiempo -y de los rostros de los actores emanan todas las corrientes subterráneas que se esconden bajo el más leve gesto, bajo el peso de una mirada-.

Hay, en el modo de abordar esta escena, algo muy minimalista y, a la vez, extraordinariamente poderoso. Un primer plano, blanco y luminoso, de Dominique Reymond: 8 segundos de silencio total dedicados a romper una barrera, a filmar el nacimiento de la sonrisa que, con dificultad, se va esbozando en su rostro. Y después el contraplano, fuertemente contrastado, de Jean-Pierre Léaud, sostenido –casi dolorosamente- durante 50 segundos. Es el trabajo con la duración y el primer plano -una de las grandes potencias del cine de Garrel- lo que dota a esta escena de su gravedad. Es la tensión que sacude al arte del retrato cuando este se enfrenta al latido del tiempo -y de los rostros de los actores emanan todas las corrientes subterráneas que se esconden bajo el más leve gesto, bajo el peso de una mirada-.

Hay un detalle muy hermoso, la entrada de la música, que está situado justamente en el corte. Es significativo que sea en este momento, tras filmar esa sonrisa de Hélène que es como una invitación, y no antes, cuando comienza a sonar “Eye to Eye”, una de las 23 piezas para piano que conforman la banda sonora del filme compuesta por John Cale. Toda la emoción de la escena explota en ese instante -con la primera nota musical, con la transición al plano de Jean-Pierre Léaud- y, a partir de ahí, se desborda de un modo asombroso. Proyectada en el rostro del actor, esta pieza de Cale inscribe, en la superficie del filme, el misterio de unas emociones y unos pensamientos que no pueden expresarse en palabras. La complicidad es tal que, durante los 50 segundos de ese plano fijo en el que Marcus mira a Hélène, se diría que los párpados cansados del actor descienden intermitentemente por el efecto de los graves del piano.

Y finalmente está, por supuesto, el filme mismo: todo lo que precede y sucede a este momento. “Lo que hará que sea una obra maestra serán los años que apilaré encima”, dice Marcus a Paul en una escena anterior. El nacimiento del amor se debate entre dos fuerzas opuestas que se encarnan nítidamente en el conflicto al que se enfrenta Paul. Por un lado está la energía que impulsa al personaje hacia sus jóvenes amantes, la de los encuentros furtivos y las primeras confesiones, la de los cuerpos como horizonte donde se conjugan todas las posibilidades. Y, por el otro, está el peso de un presente que se ha ido construyendo día a día: promesas, recuerdos y sacrificios acumulados a lo largo de años de convivencia; el matrimonio, la familia, los hijos.

En términos de significación quizás la escena que nos ocupa esté más cerca de la segunda de estas fuerzas. Es ese pasado compartido lo que hace que el plano/contraplano de Marcus y Hélène sea grave. Pero lo más hermoso es que, en términos de intensidad -en el modo en que el cineasta captura un momento precioso que deja su trazo en la zona más sensible de la película-, esta escena es el equivalente, en justicia poética, a esos encuentros que Garrel filma como ningún otro cineasta y en los que, de una mirada o de un gesto, brota el deseo: el nacimiento del amor. Es, en definitiva, la escena de reconciliación matrimonial que Garrel no puede incluir en la historia de Paul, quizás porque se siente demasiado identificado con la energía que impulsa a este personaje.

Pero el desenlace del filme contiene una declaración importante. Paul se despide de su joven amante (Aurélia Alcaïs) en la boca del metro. Ella le pide que le demuestre que la ama, a lo que él responde: “Si quieres, te hago un hijo”. Es un final sobrecogedor, lleno de esperanza. Una nueva oportunidad donde la aventura del amor y la apuesta por un amor que se extienda en el tiempo se dan la mano. Ese es, quizás, el deseo de Garrel. Porque “lo que hará que sea una obra maestra serán los años que apilaré encima”.

II. Amantes exigentes

El difunto Raúl Ruiz propuso una vez esta elegante fórmula: Garrel = Straub-Huillet + Cassavetes. Y, a continuación, ofreció una inmortal descripción de Garrel como artista, narrador y persona: la de un hombre “triste y orgulloso de ello”.

1969: Agnès Varda está viviendo en los Estados Unidos. Allí realiza, además de otros proyectos, Lion’s Love, una docuficción sobre la contracultura donde, entre otros agitadores de la escena artística del momento, aparecen Viva -la superestrella de Warhol- y los creadores del musical Hair. En 1993, en Australia, Varda recordaba despreocupadamente el estilo de vida de esa época: “Vivíamos todos juntos, en comunidad. Cada noche cambiábamos de compañero. Te excitabas y no sabías con quién te ibas a la cama ni de quién era la cama. Te dabas cuenta a la mañana siguiente, cuando te despertabas y bueno… Tu novio o novia se estaba levantando también en la cama de otro. Estaba bien, así es como funcionaba en aquella época…”.

69: una señal con este número abre la sección post-1968 de Les amants réguliers (2005), 87’30’’ en el DVD. Economía, claridad, casi un elemento naïf en la narración de este fragmento expositivo-informativo: algunas de las marcas de estilo características de Garrel. A esto podemos añadir un gusto, muy cultivado y elaborado, por la discontinuidad, la elipsis, la sorpresa, la sacudida, la revelación repentina de un detalle significante que había permanecido enterrado o suprimido hasta ese momento: aparentemente los signos de una improvisación que no da importancia alguna al guión, a la puesta en escena, al rodaje o al montaje.

Pero nada más lejos de la verdad. Cuanto más estudiamos los filmes de Garrel, más nos damos cuenta de su precisión, de su exigencia: la decisión que debe ser tomada, la única decisión posible sobre el plano, sobre su duración, sobre el lugar que ocupa dentro del filme y sobre el momento en que empieza y termina. Y también sobre el sonido, el silencio o la música que debe acompañarlo.

Triste y orgulloso de ello: esto indica una lucidez que (todavía) no ha sido invadida por una excesiva melancolía o sentimentalismo. Cuando, en Les amants réguliers, Garrel describe algunos de los fenómenos sociales y personales que Varda trató en Lion’s Love –me refiero, sobre todo, al “amor libre” o, si usamos ese terrible término moralista, a la promiscuidad-, él adopta la misma actitud, la misma responsabilidad ética, articulada en J’entends plus la guitare (1991) en relación al consumo de drogas: aquí están, os las doy como modelo o ejemplo (y esto es algo que los filmes no pueden dejar de hacer); así que, si es lo que queréis, elegidlo, imitadlo, disfrutadlo por lo que es y por lo que puede ofreceros. Pero sabed también que es inevitable que sufráis a causa de ello. Sabed que mantenerlo a largo plazo –el amor, la rebelión, el subidón, la ambigüedad sexual, un gesto inconformista radical cualquiera, sea cual sea- va a ser un trabajo duro que, probablemente, hará que algún día os desmoronéis y os conducirá a una posible desilusión, al desespero, a una depresión profunda o al suicidio.

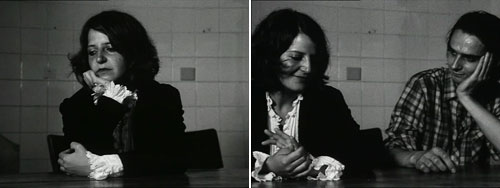

En el minuto 91 de Les amants réguliers se produce una repentina parada, una suspensión: el rostro de una mujer, Shad, interpretada por Raïssa Mariotti. Es uno de esos retratos que estuvieron presentes en el cine de Garrel durante muchos años y a los que ahora vuelve, periódicamente, dentro del marco de la ficción. Introducido en el flujo de la historia, este plano parece mucho más largo y rompedor de lo que es, objetivamente, en realidad. El crítico de The Guardian se quejaba de que estuviese “sostenido durante tanto tiempo”, ¡pero lo cierto es que dura solo 25 segundos! Y el plano inmediatamente posterior, el diálogo entre Shad y Jean-Christophe (Éric Ruillat), dura casi el doble. Pero sabemos por qué este retrato deja una huella profunda en el espectador: es fijo y es mudo -Garrel elimina el sonido ambiente para reintroducirlo tras el corte a la siguiente imagen-. Tal y como sucede con toda una serie de variados mecanismos –la inclusión de planos en negro, por ejemplo-, la aparición de este rostro actúa perforando el filme, haciendo un agujero en su progresión.

Las lágrimas en un rostro: una mujer que llora, al estilo de Picasso. Garrel las ha filmado con frecuencia y volverá a hacerlo, sin duda. In media res: no hay preparación dramática para esta aparición, incluso el momento del lloro ha pasado ya; lo que vemos es la cara húmeda, la mirada abatida, el mentón apoyado pesadamente sobre la palma de la mano. Un rostro meditabundo inmerso en pensamientos que nunca conoceremos, que nunca descifraremos: para Garrel, indudablemente, algo del secreto fundamental del cine está aquí, en esta visión que combina recuerdos o evocaciones del cine mudo con ecos de las prácticas experimentales (Chelsea Girls, de Andy Warhol, un filme que Garrel amaba allá por el 69). Y hay un detalle extraordinario que se vuelve muy intenso cuando uno lo reconoce adecuadamente: el único elemento del plano que indica que no nos encontramos ante un fotograma fijo (tal y como imaginó el crítico de The Guardian durante sus 25 segundos de interminable tortura) es la manga florida de la blusa de Shad, que ondea suavemente. Pero… ¿de qué brisa interior es producto este ondeo? De hecho, lo que provoca el delicado movimiento de la prenda es un pequeño gesto corporal: la respiración agitada de Shad. Nadie filma los diminutos trastornos sísmicos del cuerpo psicosomático como lo hace Garrel.

No tardamos en relacionar el significado narrativo de este momento con su fuerza dramática: el novio de Shad, Antoine (Julien Lucas), está durmiendo esta noche con otra chica llamada Camille (Marie Girardin). Y pronto también Shad buscará –o encontrará- consuelo en los brazos de Jean-Cristophe. Les amants réguliers se desvía de aquellos que han sido designados como héroes: François (Louis Garrel), visto por última vez enfurruñado en un sofá mientras sus compañeros bailan alegremente al ritmo de los Kinks, y Lilie (Clotilde Hesme). Por un momento, el filme vira bruscamente para posar su mirada sobre el drama de Shad. Pero después se aleja de él con la misma rapidez.

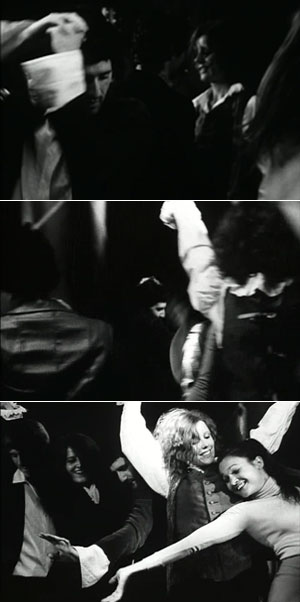

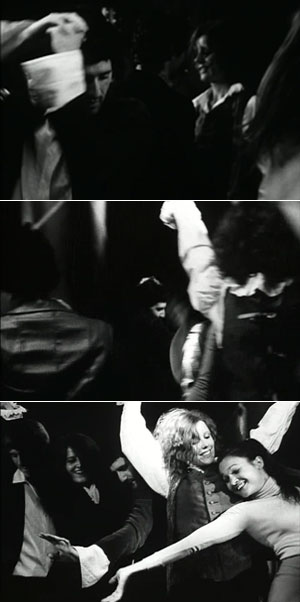

¿De dónde viene esta escena en Les amants réguliers? En parte, de ningún lugar: ese es su poder y eso es algo muy frecuente en el cine de Garrel. Como Rivette, Garrel es un maestro de la forma de “una sola cosa cada vez”, de la escena como bloque autónomo, como isla. En la magnífica y lírica secuencia del baile podemos observar -pese a que Garrel lo desenfatiza con destreza- la disgregación de todas las parejas en una coreografía muy fluida –es muy fácil confundir a varios grupos de personajes en un examen superficial-, centrada alrededor de la figura, exuberantemente queer, del “trickster” Gauthier (Nicolas Maury); y, por supuesto, la apertura a ese futuro (inmediato) subrayado por la maravillosa elección del tema de los Kinks: “This time tomorrow… what will we be?”.

¿De dónde viene esta escena en Les amants réguliers? En parte, de ningún lugar: ese es su poder y eso es algo muy frecuente en el cine de Garrel. Como Rivette, Garrel es un maestro de la forma de “una sola cosa cada vez”, de la escena como bloque autónomo, como isla. En la magnífica y lírica secuencia del baile podemos observar -pese a que Garrel lo desenfatiza con destreza- la disgregación de todas las parejas en una coreografía muy fluida –es muy fácil confundir a varios grupos de personajes en un examen superficial-, centrada alrededor de la figura, exuberantemente queer, del “trickster” Gauthier (Nicolas Maury); y, por supuesto, la apertura a ese futuro (inmediato) subrayado por la maravillosa elección del tema de los Kinks: “This time tomorrow… what will we be?”.

Hay una confusión sutil y contagiosa en la difusa relación de causa-efecto entre los dos eventos, entre el primer contacto de Antoine con Camille (con el que concluye la escena del baile) y las lágrimas de Shad: ¿ha llegado esta a ver a la otra chica? ¿En qué momento se ha dado cuenta de su pérdida? Garrel emborrona todo esto con la seguridad del pintor que difumina una línea del lienzo que, hasta entonces, había permanecido clara. Esa es la gravedad y la exigencia de Garrel.

Portraits

Click aquí para la versión en español

I. Eye to Eye

Where lies the mystery of those images that strike you the first time you see them, and whose trace haunts you for the rest of your life? There is a scene in The Birth of Love (La naissance de l’amour, Philippe Garrel, 1993) whose flash wildly inflamed something that still cannot be named or explained. More than a scene, it is a fragment of sustained time: a shot/counter-shot, almost a minute long, in which a man and a woman reunite, after a long separation, and gaze into each other’s eyes. It happens right near the film’s end, when Paul (Lou Castel) and Marcus (Jean-Pierre Léaud), the two best-friend-protagonists, travel from Paris to Rome in search of the latter’s wife, Hélène (Dominique Reymond), who has left him for another man. Once there, Marcus calls Hélène by telephone and she, perhaps surprisingly, says to him: “Come”.

I am dealing with a moment that has extended itself in my memory, coming to claim a greater space than what it actually occupies in the film’s running time. This must doubtless be because, in these two close-ups of the couple’s faces, we sense something concentrated. The shots are loaded, grave and, at the same time, intense. But this loading, this graveness, this intensity … where do they come from? How can two images create such an affect, installing themselves in a secret corner of our memory in order to intermittently return down the course of the years, insistent and overexposed, like the ghosts in Garrel’s films?

There is, in the way this scene is approached, something extremely minimalist and, at the same time, extraordinarily powerful. A first shot, white and luminous, of Reymond: 8 seconds of total silence dedicated to lifting a barrier, filming the birth of the smile that, with some difficulty, comes to be traced on her face. And then the counter-shot, strongly contrasting, of Léaud, which is sharp – almost painfully so – for 50 seconds. It is the work on duration and the close-up – one of the great powers in Garrel’s cinema – that gives the scene its gravity. This is the tension that shakes the art of portraiture when it meets time’s pulse – releasing, on the actors’ faces, every subterranean current that hides beneath the slightest gesture or the deepest gaze.

There is, in the way this scene is approached, something extremely minimalist and, at the same time, extraordinarily powerful. A first shot, white and luminous, of Reymond: 8 seconds of total silence dedicated to lifting a barrier, filming the birth of the smile that, with some difficulty, comes to be traced on her face. And then the counter-shot, strongly contrasting, of Léaud, which is sharp – almost painfully so – for 50 seconds. It is the work on duration and the close-up – one of the great powers in Garrel’s cinema – that gives the scene its gravity. This is the tension that shakes the art of portraiture when it meets time’s pulse – releasing, on the actors’ faces, every subterranean current that hides beneath the slightest gesture or the deepest gaze.

A very beautiful detail – the entrance of the music – is located exactly at the cut. It is significant that this – the beginning of “Eye to Eye”, one of the 23 pieces that comprise the soundtrack composed by John Cale – happens right here (after the shot of Hélène’s smile, which is like an invitation), and not beforehand. For the entire emotion of the scene explodes at this moment – on the first musical note, on the transition to the shot of Léaud – and, from there, it flows forth in an astonishing fashion. Projected into the actor’s face, this piece by Cale inscribes, on the surface of the film, the mystery of emotions and thoughts that cannot be expressed in words. The complicity is such that, during the 50 seconds of this fixed shot in which Marcus watches Hélène, it might be imagined that the actor’s heavy eyelids intermittently blink in time with certain falling piano notes.

And finally it is, of course, the whole film; it includes everything that comes before and after this moment. “What will make a masterpiece are the years I’ll put into it”, says Marcus to Paul in a previous scene. The Birth of Love negotiates between two opposing forces that are clearly incarnated in the conflict Paul faces. On the one hand, there is the energy that impels the character towards his young lovers, the furtive encounters and first confessions, these bodies as a horizon where all possibilities can be imagined. And, on the other hand, there is the weight of a present that has been constructed from day to day; promises, memories and sacrifices accumulated down the years of cohabitation – marriage, family, kids.

In terms of its meaning, the scene that concerns us is perhaps closer to the latter of these two forces. It is that shared past which makes the shot/counter-shot of Marcus and Hélène so heavy. But the most beautiful thing is that, in terms of intensity – the manner in which the filmmaker captures a precious moment that leaves its trace on the uppermost layer of the celluloid – this scene is the equivalent, in its poetic justice, to those encounters that Garrel films as no other director can, the encounter that, with a look or a gesture, brings forth desire: the birth of love. It is, ultimately, the scene of marital reconciliation that Garrel cannot include in Paul’s story – perhaps because he overly identifies with the energy that drives this character.

But the film’s ending contains an important declaration. Paul takes leave of his young lover (Aurélia Alcaïs) at the entrance to the métro. She asks him to demonstrate his love for her, and he responds: “If you want, I’ll give you a child”. It is a moving conclusion, bursting with hope. A new opportunity wherein love’s adventure, this bet on a love that can extend through time, offers its hand. And this is, perhaps, Garrel’s own desire. Because “what will make a masterpiece are the years I’ll put into it”.

II. Exigent Lovers

The late Raúl Ruiz once elegantly proposed the following formula: Garrel = Straub-Huillet + Cassavetes. And, in the same breath, he went on to offer an immortal description of Philippe Garrel as an artist, a storyteller and an individual: he is sad and proud of it.

1969: Agnès Varda lives in the USA, making (among other projects) Lion’s Love, a doco-fiction on the counterculture with (among other scene-makers) Warhol’s superstar Viva and the co-devisers of the musical Hair. In 1993, in Australia, Varda whimsically recalled her lifestyle of that period: “Everybody lived together communally. You swapped your bed partner every night. You got high and you didn’t know who you went to bed with, or whose bed it was. Next morning, you woke up and found out, oh well … And your boyfriend or your girlfriend was waking up in someone else’s bed too … It was OK, that’s how it went, back then …”

69: the street sign bearing this number opens up the post-1968 section of Les amants réguliers (2005), 87 and a half minutes into the DVD. Economy, matter-of-factness, almost an element of naïveté in the narration of this bit of exposition-information: some hallmarks of Garrel’s style. To which we can add a highly cultivated and elaborated taste for discontinuity, ellipsis, surprise, a jolt, the sudden revelation of significant but hitherto buried or suppressed detail: seemingly the signs of an off-hand, couldn’t-care-less scripting, staging, shooting and editing manner.

But nothing could be further from the truth. The more we study Garrel’s films, the more aware we become of their precision, their exigency: the one decision that has to be made, the only decision that can be made as to the shot, its length, its opening and closing, and its placement. And the sound, or silence, or music that should best accompany it.

Sad and proud of it: that indicates a lucidity not (yet) overrun by excessive melancholia or sentimentality. When Garrel depicts in Les amants réguliers some of the same personal-social phenomena that Varda treated in Lion’s Love – ‘free love’ being the central item for my purposes here, or (to give it that awful, moralistic term) promiscuity – he adopts the same attitude, the same ethical responsibility, that he articulated in relation to the depiction of drug use in J’entends plus la guitare (1991): here it is, I give it to you as a model or example (films cannot help but do this), so if you want to, choose it, emulate it, enjoy it for what it is and what it can do for you – but also know that you will suffer, inevitably, because of it. Know that maintaining it across time – love, revolt, getting high, gender fluidity, whatever radical, nonconformist gesture it is – is going to be hard work, and is probably going to someday fall apart, leading to a potential disillusionment, despair, deep depression or suicide.

At the 91 minute mark of Les amants réguliers, a sudden full-stop or suspension: the face of a woman, Shad played by Raïssa Mariotti. It is a portrait of the kind that Garrel’s cinema once spent so many years with, and periodically returns to within the framework of fiction. Coming like this within the flow of a story, it seems to run for far longer, to be far more disruptive, than it actually, objectively is: this shot that The Guardian complains is “held for such a long time” is scarcely 25 seconds in length! And the shot that immediately follows it – the dialogue between Shad and Jean-Christophe (Éric Rulliat) – is almost twice as long. But we know why the close-up portrait makes its mark on the viewer in this way: because it is both still, and silent – Garrel removing all sound for the entire shot, and only re-introducing ‘room tone’ on the cut to the next image. The appearance of the face punches a contemplative hole in the film’s progression – as do a barrage of other devices throughout, such as the black frames.

A face in tears – a Picasso-esque Weeping Woman. Garrel has often filmed them, and no doubt will again. In medias res: no dramatic preparation for this apparition, even the sobbing itself has already passed; what we witness is the wet face, the downcast eyes, the chin held heavily in the palm of the hand. A pensive visage thinking thoughts we will never know, never decipher: for Garrel, something of the most primal secret of cinema is surely here, in this sight. It combines memories or evocations of silent cinema with echoes of experimental film practices (like Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, which Garrel loved around ’69). And there is an extraordinary detail here, so intense once one recognises it for what it is: the only element in the shot that indicates we are not looking at a still (as the Guardian critic imagined during his 25 seconds of interminable hell!) is the fluttering of Shad’s ornate shirt sleeve. But … fluttering, in what indoor breeze? In fact, it is a tiny bodily gesture, Shad’s disturbed breathing through her nose, moving the delicate fabric. No one records the small, seismic disturbances of the psychosomatic body like Garrel.

We put together the narrative meaning and dramatic force of this moment quite quickly: her man, Antoine (Julien Lucas), is sleeping with someone else tonight, namely Camille (Marie Girardin). And Shad, too, will soon seek – or rather, find – solace in another man’s arms, those of Jean-Christophe. Les amants réguliers ‘glances’ into this drama as it swerves away, for a time, from its nominal hero and heroine, François (Louis Garrel) – last seen before this sulking on a couch while his companions joyously dance to The Kinks – and Lilie (Clotilde Hesme). And it glances away just as quickly.

Where does this scene come from in Les amants réguliers? Partly, out of nowhere: that is its power, as so often in Garrel. Like Rivette, Garrel is a master of the ‘one thing at a time’ form, the scene as autonomous block, as island. In the magnificent, lyrical dance scene of the film, we can observe – completely unstressed by Garrel’s craft – the ‘de-aggregation’ of all couples in the fluid choreography (it is very easy to confuse various sets of characters on a casual perusal), centred around the flamboyantly queer ‘trickster’ figure of Gauthier (Nicolas Maury); and of course, the openness to the (immediate) future underlined by the wonderfully chosen Kinks song “This Time Tomorrow … what will we be?”

Where does this scene come from in Les amants réguliers? Partly, out of nowhere: that is its power, as so often in Garrel. Like Rivette, Garrel is a master of the ‘one thing at a time’ form, the scene as autonomous block, as island. In the magnificent, lyrical dance scene of the film, we can observe – completely unstressed by Garrel’s craft – the ‘de-aggregation’ of all couples in the fluid choreography (it is very easy to confuse various sets of characters on a casual perusal), centred around the flamboyantly queer ‘trickster’ figure of Gauthier (Nicolas Maury); and of course, the openness to the (immediate) future underlined by the wonderfully chosen Kinks song “This Time Tomorrow … what will we be?”

There is a subtle, infectious confusion in the blurry cause-and-effect connection of the two events, Antoine’s hook-up with Camille (which concludes the dance scene), and the tears of Shad: did the latter actually see the former, at what point did she become aware of her loss? Garrel confidently smudges all this, as a painter smudges a hitherto clear line on the canvas. This is the gravity and exigency of Garrel.

(*) «Amantes exigentes» ha sido traducido del inglés por Cristina Álvarez López con la colaboración del autor

(*) «Eye to Eye» has been translated from the Spanish by Adrian Martin with assistance from the author

Textos y traducciones © Cristina Álvarez López y Adrian Martin Diciembre 2011 / Texts and translations © Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin December 2011