L’enfant secret

Jardín de piedra: L’enfant secret (Philippe Garrel, 1982)

Click here for the English version

En junio de 2001, cuando finalmente pude ver L’enfant secret (1982) como parte de una conferencia sobre Philippe Garrel en Dublín (1)↓, se resolvió un dilema para mí. Había estado enamorado del trabajo de este director desde el único -y, en mi caso, trascendental- pase de Les baisers de secours (1989) en Melbourne, en 1994. Un año después, tras haber visto J’entends plus la guitare (1991) y El nacimiento del amor (La naissance de l’amour, 1993), no sabía cuál nominar como mi filme favorito, si este último o Les baisers de secours.

Desde ese momento me las he arreglado para ver la mayoría de la producción de Garrel, empezando por las últimas obras y llegando a las primeras fases de su trabajo durante los sesenta y setenta. Todos los filmes son fascinantes y muchos de ellos, incluyendo Liberté, la nuit (1983), Le lit de la vierge (1969) y Rue Fontaine (1984), son formidables, con J’entends plus la guitare creciendo en mi memoria con el paso del tiempo. Siempre había tenido muchas ganas de ver L’enfant secret -el filme que, como todos los leales “garrelianos” saben, marca el principio de su periodo narrativo y la reanudación de su proyecto autobiográfico abandonado después de su primer corto, Les enfants désaccordées (1964)-, pero no imaginaba que el visionado de este filme se convertiría en una experiencia tan extraordinaria y abrumadora. L’enfant secret es, en todos los sentidos, el filme central de la carrera de Garrel. Desde mi punto de vista también es, indiscutiblemente, el mejor de todos ellos.

Una cualidad del cine que valoro casi en grado supremo es la intensidad. L’enfant secret es un filme incomparable e implacablemente intenso, con un nivel de emoción extraordinariamente sostenido, oceánico. De todos los trabajos autobiográficos realizados por Garrel desde 1982, este es el que se acerca más directamente a los episodios de su vida. Mientras en sus últimos filmes la figura que funciona como su álter ego se transmuta de director de teatro en escritor, pintor y arquitecto, aquí Jean-Baptiste (Henri de Maublanc) es un director de cine. Quizás solo en la elección de Anne Wiazemsky como Elli (el personaje que remite a Nico) -Garrel dijo de ella que “era una princesa francesa interpretando a una trabajadora alemana”- vemos el primer signo de su creativa y polifacética exploración del casting (tal y como ha sugerido Fabien Boully, el cine de Garrel es un auténtico arte del casting), así como su noción de las posibilidades ficticias del autorretrato novelado. El propio título del filme -derivado, sin duda, de la vida misma, pero también de una canción de Juliette Greco- alimenta esta atmósfera de lo novelesco.

El filme traza una sucesión de eventos que comienza con el primer encuentro de Jean-Baptiste y Elli en una casa comunal y prosigue con un periodo de amor idílico, hasta que la separación sume a Jean-Baptiste en una psicosis inducida por las drogas. Esto precipita su posterior ingreso en un hospital donde es sometido a una terapia de electroshock. Después, los amantes se reúnen de nuevo, pero la muerte de la madre de Elli la sumerge en una espiral depresiva que la acaba conduciendo a la adicción a la heroína. El niño secreto del título es el hijo de Elli; Garrel explica -aludiendo al hijo de Nico y Alain Delon- que “ella tuvo un niño con un conocido actor que no lo reconocería como tal” (2)↓. Nótese que Garrel selecciona y da un énfasis distinto a cada fragmento de su novela autobiográfica: durante mucho tiempo, por ejemplo, conservó sus recuerdos de la experiencia de mayo del 68 para la magistral Les amants réguliers (2005).

Encarnado por el modelo “bressoniano” de Maublanc, Jean-Baptiste es, de todos los dobles del director, el más sorprendentemente moroso, hundido y corpulento, mientras el personaje de Elli es extremadamente complejo, enigmático y conmovedor. En el cine de Garrel el trauma de una persona que crece y tiene que enfrentarse finalmente al orden simbólico de la edad adulta (y a la paternidad/maternidad), después de sufrir la muerte de uno de sus amados progenitores, tiende a ser, normalmente, una historia masculina. Pienso sobre todo en El corazón fantasma (Le coeur fantôme, 1996), aunque solo sea porque los problemas masculinos son aquellos con los que Garrel está más familiarizado, a pesar de que él, cada vez más durante la última década, ha declarado estar orgulloso de ceder el control a las mujeres en escenas que han sido escritas y guionizadas por ellas (3)↓. L’enfant secret es la asombrosa excepción a esta regla. La pena de Elli tras la muerte repentina de su madre y el efecto catastrófico que esta tiene en su futuro desarrollo es algo que se siente de una manera muy poderosa en este filme. El salmo de Wiazemsky repitiendo “mamá”, que tiene lugar en una de esas escenas de tren omnipresentes en el cine de Garrel, es tan lacerante como el del hijo que grita incesantemente “papá” en El nacimiento del amor. Curiosamente este aspecto de la historia de Nico (asumiendo que de verdad esté basado en su vida real) es ignorado en J’entends plus la guitare que es, quizás no en forma pero sí en contenido, el filme de Garrel más cercano a L’enfant secret.

Pese a que nunca deberíamos negar la realidad material y física de los personajes de Garrel, ni tampoco la aguda observación -que el director integra en la narración- de su psicología y de su comportamiento, al hablar de los personajes en esos términos corremos el riesgo de borrar la cualidad especial de L’enfant secret. En muchos aspectos se trata de una película icónica, construida solo a partir de momentos álgidos muy vívidos y comprimidos -la clase de filme que muchos sueñan con hacer pero que pocos pueden llevar a la práctica con éxito-. Los personajes no reciben un tratamiento psicológico convencional ni tampoco son los emblemas graves, internados en la geometría de sus soledades cruzadas, que encontramos en Le vent de la nuit (1999). En L’enfant secret, lo que le importa a Garrel son los flashes puros de los estados intersubjetivos: la unión y la separación, el desespero y la enajenación, el éxtasis de la pérdida del yo y el encierro inmóvil, infernal. Aunque, esencialmente, estamos ante un filme lineal, la única lógica esencial que lo rige es la de la contradicción cruda entre una escena y la siguiente: nada ni nadie permanece estático o unificado por mucho tiempo. Las escenas de cama, un motivo central del cine de Garrel, son ya usadas aquí para conjurar este caleidoscopio lleno de situaciones, tensiones, sensaciones.

Cuando he sugerido anteriormente que L’enfant secret es, en todos los sentidos, el filme central de la carrera de Garrel, me refería principalmente al sentido cronológico y al descriptivo. El filme se sitúa en la cúspide de las dos mitades que, por el momento, forman su obra. Si bien esta película inaugura el periodo narrativo de Garrel, en sí misma no es narrativa más que de una manera tímida y tenue -lleva a los dos protagonistas del punto A al B y eso es todo-. Podríamos decir que es, simultáneamente, un filme de ficción y un filme-retrato, la joya de la corona de una serie de trabajos hechos en los setenta (incluyendo la notable Les hautes solitudes, 1974) (4)↓. Un trabajo sobre la duración atenuada -o, en palabras más precisas de Alain Philippon, sobre “la alternancia de aceleraciones y deceleraciones, de rupturas y de tramos despejados” (5)↓ -que marcará, a partir de aquí, todo su trabajo en los filmes-retrato y que viene a concentrarse, en L’enfant secret, en miradas intersubjetivas, abrazos y momentos de tensión congelados (a veces inescrutables).

En Les hautes solitudes esa intersubjetividad existe, pero va del sujeto situado ante la cámara hasta Garrel, el operador que está tras ella. En L’enfant secret, cuando salen a la luz los daños de una desgarradora escena de amor, Elli acusa a Jean-Baptiste de tener “una cámara en el lugar del corazón”. Ahora también podemos ver, examinando el trabajo de los setenta, cómo algunos motivos clave e imágenes hipercargadas de Garrel -por ejemplo: esas en las que vemos a personas durmiendo, caminando o a una mujer apoyada en la ventana- pasan directamente del filme-retrato (donde estas se generan como una evidencia primaria, espontánea, documental) a las ficciones.

En la vertiginosa cumbre de este arte del retrato, no hay en el cine de Garrel un pasaje más divino o desgarrador en su eterna quietud y en su repetición interna que ese de L’enfant secret -emplazado cerca del minuto 15- en el que Jean-Baptiste y Elli, en la calle, son congelados en un abrazo nocturno y, pese a que parecen incapaces de decirse adiós, están forzados a separarse. Todo el tira y afloja de la intensidad del filme se concentra en esa preciosa combinación de imágenes, gestos y música.

Al mismo tiempo L’enfant secret vuelve al trabajo de los sesenta de Garrel, pero de un modo fantasmal, recogiendo sus ecos distantes. Mientras la fase de los setenta inaugura un “arte povera”, su trabajo de los sesenta -el periodo de Zanzíbar- es, por lo menos en el contexto del experimental, rico, lujurioso, expansivo, un momento de esteticismo dandy. Un periodo que vibra con el sentimiento contracultural del mito atemporal, ritual y mágico (que se extiende a los filmes dirigidos por su colaborador Pierre Clémenti) centrado, normalmente, en el imaginario de la Santa Familia. En L’enfant secret el trío formado por la madre, el padre y el hijo ha caído a la Tierra y está, internamente, incluso más tenso y dividido que en Le révélateur (1968). Las huellas de la visión de los sesenta (6)↓ las encontramos, esencialmente, en los intertítulos que, no sin misterio, dividen al filme en partes: “La operación cesárea”, “El círculo Ofidio”, “El último de los guerreros”, “Los bosques desencantados”. La riqueza de L’enfant secret deriva de una tensión entre la elevada poesía evocada por esos títulos -imágenes basadas en la naturaleza: el nacimiento, el peligro, el idilio, los ciclos nocturnos y diurnos, el clima, el reino animal; quizás también un reflejo de las letras de las canciones de Nico- y las pequeñas, incluso miserables, vidas y sucesos referidos.

Raymond Bellour tuvo la astucia de poner en relación L’enfant secret con la reciente Sombre (Philippe Grandrieux, 1998): “Desde L’enfant secret de Philippe Garrel no había visto en el cine francés una película tan nueva y moderna dirigida por alguien tan joven” (7)↓. Hay mucho más que conecta a ambos filmes: el punto de vista de unas emociones y una experiencia que están claramente marcadas por un entendimiento de los impulsos humanos muy influenciado por el psicoanálisis (en ambos filmes hay una escena verdaderamente fundamental: la de un niño que ve una película como si fuera la primera vez), una sutil pero crucial referencia al reino de los cuentos de hadas (más fuerte en el filme de Grandrieux que en el de Garrel) y una exploración asombrosamente intrincada de toda una serie de técnicas prohibidas dentro del cine convencional. Estas técnicas incluyen: luz y oscuridad extremas (a partir de la sobreexposición y la subexposición), la preferencia -asociada al cine mudo- por el silencio, la música y el ruido sobre el diálogo; un tipo de imagen borrosa producida por el desenfoque (sería necesario que alguien escribiese una historia fílmica del desenfoque, por lo menos para redimirlo de la moda actual que usa esta técnica en anuncios y vídeos de rock).

En mi opinión L’enfant secret va incluso más lejos que Sombre. La inventiva formal del filme de Garrel es prodigiosa: destellos, planos que se repiten, planos en negro, refilmación a partir de imágenes de la moviola, filmación a través de varios tipos de superficies de cristal, un asombroso trabajo composicional de descentralización del cuadro (uno de los planos más hermosos del filme nos deja ver unos ojos diminutos sin rostro a través de las abundantes hojas de un árbol). Algunas escenas empiezan repentinamente, de manera impactante, con el filme levantando el vuelo en una estratosfera que, hasta entonces, no nos era familiar: cuando Jean-Baptiste rompe con violencia un cristal, o cuando Elli intenta saltar por una ventana; el momento en que dos hombres arrastran por la fuerza a Jean-Baptiste hasta el hospital mientras en la banda de sonido escuchamos su voz sin cuerpo profiriendo una sola palabra: “Resiste”. De todos los trabajos de Garrel este es el que se encuentra, de modo más extremo, en pleno proceso de disipación y desintegración.

El efecto de todo esto es asombroso, a veces desconcertante, ofreciéndonos un flujo hipercargado al que, finalmente, debemos rendirnos -pocos filmes suspenden, como este, la noción del tiempo real-. Uno aprecia mejor las odiseas poéticas de Liberté, la nuit –especialmente su dualidad “godardiana” entre el lirismo tierno y la violenta brusquedad- habiendo visto el filme que lo precede y prepara el camino hacia él; pero Liberté, la nuit, por todas sus cualidades, ya es un paso hacia ese estilo más limpio de un cine de arte y ensayo que Garrel adoptará por entero en Le vent de la nuit, -y solo temporalmente, tal como han demostrado Salvaje inocencia (Sauvage innocence, 2001) y La frontera del alba (La frontière de l’aube, 2008)-.

En contraste, L’enfant secret nos lleva muy cerca de una imagen-sueño que, durante mucho tiempo, ha estimulado cierta discusión sobre el cine, especialmente en los campos del experimental, el underground, el súper 8 y la animación: la idea de que algunos trabajos, algunas formas, pueden llevarnos cerca del propio “inconsciente del filme”, un lugar inclemente, elemental y barroco donde el lenguaje (de cualquier tipo) está todavía estructurándose en la vorágine de la presignificación, donde todos los impulsos se superponen en su impersonal intensidad, y la propia materialidad del medio está expuesta a sus terminaciones nerviosas más sensibles. El radical trabajo de Garrel con el efecto flicker y con la exposición inflama este sueño, al igual que lo hace la presencia del ruido de la cámara que es una parte integral de la textura del filme -verdaderamente uno siente que está asistiendo, como una comadrona, al nacimiento del cine-.

En otro nivel de heterogeneidad, está la deslumbrante música de Faton Cahen y Didier Lockwood. Siempre me ha impresionado el uso que hace Garrel de la música como gesto. El modo en que, al aislarla o retrasar su entrada, enfatiza su emplazamiento preciso. Pero L’enfant secret nos coloca ante el más atrevido de esos gestos. Los primeros diez minutos del filme son completamente mudos, hasta que esa increíble música invade la escena y se eleva, apoderándose de largos fragmentos del filme. En un juego que volverá a hacerse presente, de un modo más suave y lírico, en Les baisiers de secours, llega un momento en el que la música y el diálogo, entrelazados, compiten por el dominio auditivo, apareciendo y despareciendo uno dentro del otro, mientras los personajes pasean.

El shock que experimenté viendo L’enfant secret me ayudó a apreciar la importancia de cierta, inextricable, experiencia de la Otredad o de la alteridad en el cine de Garrel. Esta cruda presencia del otro toma muchas formas en su trabajo; su maestría en esos niveles de ambigüedad y extrañeza es uno de los aspectos que suele pasar desapercibido entre sus dotes como cineasta. Está el shock de aquellos, particularmente niños, a quienes los personajes encuentran, como el primer momento en que vemos al hijo secreto de Marianne en J’entends plus la guitare. Hay, en la misma película, la forma fascinante de un rostro desfigurado, filmado de forma clara, directa. Hay misteriosos acontecimientos que se despliegan mágicamente ante nosotros (este es el lado Dreyer de Garrel), como el instante de unión de una pareja nueva en El nacimiento del amor, el hombre que espera a que llegue su propia muerte en Le vent de la nuit, o la significativa complicidad entre Duval y Deneuve en el mismo filme (tenemos la sensación de que se han conocido antes -el encuentro embrujado, fantasmal: un tema de Blanchot muy querido por Garrel-). Hay historias secundarias (normalmente acompañadas por una sorprendente voz over) que aparecen como una ráfaga y rápidamente desaparecen: Mathieu encontrando el pendiente en Les baisiers de secours, Marcus espiando a su mujer en El nacimiento del amor. Están las notas escritas (que escuchamos en la banda de sonido, leídas espectralmente) o las llamadas de teléfono (no menos espectrales en su intrincada figuración de presencia y ausencia) que, en el cine de Garrel, son casi siempre presagios de muerte, pérdida o desastre (como en Rue Fontaine, 1984). Están sus maravillosos, poéticos títulos (corazón fantasma, niño secreto, besos de emergencia, nacimiento, viento, noche), una mezcla entre Breton y Poe, tan rica y extraña…

Hay distintas apariciones en el cine de Garrel. Psicosis: Jean-Baptiste sentado en una cama con un traje militar. Algunas visiones son francas y orgánicas (Marianne orinando, Alcaïs menstruando) y otras son obscenas, como las jeringuillas hipodérmicas que aparecen en el baño en L’enfant secret, las que vemos esparcidas por el suelo en J’entends plus la guitare y, especialmente, la encontrada junto a la niña en El corazón fantasma (un momento perturbador que Dowd, con acierto, señala como central en el trabajo de Garrel). También hay, en esta familia de apariciones, los insertos extraños y exclamativos de Garrel, como los signos o palabras inscritos en señales gráficas que presiden algunas escenas y determinan, con mucha obviedad, su lectura (el signo de “alarma” final en el andén del metro en Les baisiers de secours y el anuncio de Durex que aparece cuando Duvall entra en una farmacia y las puertas se cierran en Le vent de la nuit, mientras Deneuve observa la escena y sonríe). Finalmente hay material que va más lejos de lo meramente críptico para alcanzar lo rotundamente inasimilable o inconmensurable (ya que, fundamentalmente y en última instancia, el otro debe existir siempre en términos filosóficos).

En el cine de Garrel es fácil olvidar o censurar los momentos que vienen de ninguna parte y no reciben más explicación que el hecho de haber sido elegidos por él, atendiendo a razones secretas, para ponerlos ahí (como el dibujo con el que se inicia Liberté la nuit). Frecuentemente los filmes de Garrel empiezan con un prolegómeno (como en Le vent de la nuit) o con un viraje brusco (el retrato de la prostituta al inicio de El corazón fantasma). Les baisiers de secours, en contraste, es excepcional ya que nos sumerge en la ficción en su primer gesto, en su primera línea, cuando Sy pregunta: “¿Por qué no estoy yo en el filme?”. El inicio de L’enfant secret es extremo porque parece situarnos en el comienzo de otro filme, una película muda de amor adolescente; es difícil no especular con que esas figuras representan, simbólicamente, a los personajes principales en una encarnación más joven y mística. Esa mirada sobre otra pareja que no será el tema del resto del filme es parte de la referencia autobiográfica de Garrel a sus años en Positano (donde cohabitaron dos parejas), algo que vuelve como material en J’entends plus la guitare y, más recientemente, en Un étè brûlant (2011), dedicada a la memoria de Frédéric Pardo, pintor e íntimo amigo suyo -pero también es un emblema de la forma esencial de su trabajo, imponente y desconcertante, hermoso y escalofriante en igual medida, como un bosque desencantado o un jardín de piedra-.

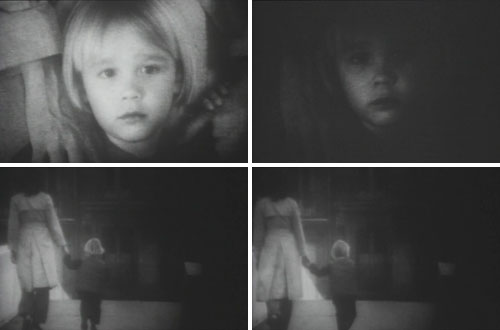

En L’enfant secret hay un recurso recurrente que es particularmente cautivador -las imágenes refilmadas del hijo de Elli, deteniéndose, poniéndose en marcha, congelándose, destellando-. Es difícil describir el poder evocador e inquietante de esas imágenes. En parte es una cuestión de tema: más brutalmente que en cualquier otro filme de Garrel este niño encarna, simultáneamente, al problemático otro que conduce a los amantes adultos a la separación (como en esa escena, casi cómica, donde no pueden dormir juntos en presencia del pequeño), y al niño perdido que es, inevitablemente y sin esperanza, abandonado por sus guardianes biológicos en el más cruel de los mundos (aquí es donde Garrel se encuentra con el Cassavetes de Love Streams, 1984]). En otro nivel, las imágenes refilmadas del niño proporcionan una puerta de entrada al más profundo nivel del inconsciente fílmico. Utilizando un truco que, a finales de los setenta quizás ya se estaba convirtiendo en un recurso común y estereotipado, Garrel pone en marcha un filme dentro del filme dirigido por Jean-Baptiste y protagonizado, según parece, por Elli y su hijo; en un momento dado él habla de un proyecto (llamado “Los bosques desencantados”) que, en realidad, era una idea que propio Garrel planeó llevar a cabo y terminó abandonando.

Pero, como de costumbre, Garrel solo nos da los elementos básicos de esta premisa ficcional. Lo que importa es que este filme dentro del filme provoca una confusión radical, contagiosa, que nos hace dudar del estatuto de todas las imágenes de L’enfant secret. En una secuencia vertiginosamente surrealista, el trío central va a un cine a ver una comedia muda; Garrel pasa de un plano de ellos en sus asientos a otro de la entrada sumergida en la oscuridad y atravesada por un extraño juego de luces. Mientras tanto, la conversación continúa y comienza a sonar la típica música de piano desentonado. Pronto veremos imágenes de los tres, acompañadas por la misma música, como si los propios personajes fueran la imagen que se está proyectando en la pantalla. Y, a partir de ahí, todo está permitido: una imagen que se repite (separada por planos en negro) de Wiazemsky en una ventana. ¿Este material pertenece al filme de Garrel o al de Jean-Baptiste? Esto no significa que L’enfant secret sea un puzle con solución, como suele suceder con los filmes de esta categoría; más bien se abre, forzosamente, al dominio del cine como reino de las imágenes mentales indecibles, que no son enteramente subjetivas ni objetivas. En este filme, que está militantemente preocupado por los estados mentales -de la depresión a la alucinación-, no podemos fijar una línea divisoria entre los planos reales, los planos fabricados y las imágenes interiores. Ni tampoco podemos separar el filme como pieza acabada (pese a que seguramente es lo que estamos viendo) de las muchas capas experimentales de su crudo, intenso y agitado proceso inconcluso.

Estas cualidades afectan a la propia constitución de la historia y a su supuesta “verosimilitud” (una palabra patéticamente inadecuada en el contexto de este filme): esas manchas pictóricas de sangre en el baño y la cama de Jean-Baptiste ¿son una evidencia de intentos de suicidio reales o algo muchísimo más conceptual? El “género” (otra palabra débil en este contexto) también se vuelve imposible de fijar: por un momento, en las escenas de electroshock, que son a la vez serenas y terroríficas, L’enfant secret se convierte en la producción más misteriosa de Val Lewton jamás realizada.

De todo lo que leí, a lo largo de los años, sobre L’enfant secret, había dos citas particulares de las que guardaba un recuerdo especial. En el curso de unas páginas magistrales sobre Garrel en La imagen-tiempo, Gilles Deleuze describe el momento del filme en el que “vemos la ventana de un café, dentro el hombre de espaldas y, reflejada en el cristal, la imagen de la mujer también de espaldas yendo a encontrarse con su camello” (8)↓. Cuando el filme se estrenó por primera vez en París, Alain Philippon (un crítico extremadamente dotado que murió en 1998) concluyó su crítica así: “Conozco pocos filmes, hoy en día, en los que el simple plano de la mano de un hombre en el cabello de una mujer pueda llevar consigo una carga emocional de tal intensidad” (9)↓. ¡Durante años he imaginado esos dos momentos cinematográficos! ¡He soñado con ellos! Pero lo que no pude adivinar es que, en realidad, ambos pertenecen al mismo plano-secuencia y ese plano es, de hecho, el final del filme.

Garrel comenta, de manera respetuosa pero sin ambages, el análisis del plano en cuestión llevado a cabo por Deleuze: “Naturalmente esta forma de doblar a Eli en dos imágenes, la real y la virtual, puede ser interpretada, pero, objetivamente, la razón para esto era la falta de recursos: tenía que filmar a través de una ventana para evitar que se escuchase más ruido de cámara…”. En el contexto de todo el filme, los desplazamientos de foco utilizados en esta escena en relación a esa superficie reflectante pueden calificarse de virtuosos. Garrel añade: “Siempre, cuando filmo, lo único que me preocupa son los problemas técnicos” (10)↓.

Garrel es demasiado modesto, porque este es uno de los finales más demoledores que he visto nunca en pantalla, con un sentido magistral del potencial dramático de la duración y la acumulación. El filme termina abandonando la historia en un momento de completa irresolución: Jean-Baptiste sabe ahora de la adicción de Elli y ella sabe que él lo sabe, así que simplemente han alcanzado un momento que es a la vez de impasse y de cansancio mutuo. Ella se lanza sobre su mano, la besa dulce pero desesperadamente (un poco como Catherine Deneuve, que también cubrirá de besos las manos de su amante en Le vent de la nuit), él acaricia su cabello en medio de un silencio brutal, ella repite, una y otra vez: “No me sermonees…”. Y entonces las luces se encienden; no hay créditos ni al principio ni al final del filme (más allá del título y los intertítulos); no hay siquiera una pantalla negra. Este es un filme de Garrel en el que su álter ego no alcanza esa frágil isla donde le espera una fugaz redención intersubjetiva; no hay ángel salvador, no hay renacimiento del amor con otra mujer. Thierry Jousse la ve como una película atravesada “por una suerte de fatiga, en el sentido en que Blanchot habla de la fatiga como un elemento constitutivo de cierto tipo de literatura moderna, o Deleuze describe a Antonioni como el cineasta que inscribió la fatiga en los cuerpos” (11)↓. Hay un cansancio existencial en el filme, sí, pero también un increíble sentido de la inventiva y de la innovación artística; y un testimonio solemne y, en última instancia, sublime de la experiencia interior.

Me gustaría mucho saber cuántas copias de L’enfant secret existen en el mundo y en qué estado se encuentra el negativo. Garrel, que fue el productor de su propio proyecto, todavía tiene que dar un permiso especial para sus escasas proyecciones; y un DVD japonés que estuvo disponible es ahora una verdadera rareza. Nunca en mi vida he estado tan embargado durante la proyección de un filme por un deseo tal de protegerlo y preservarlo. Me conmovió el sentimiento íntimo de fragilidad del propio celuloide, porque incluso los dolores de su parto arrastran esta misma aura: según Garrel se completó en 1979 y permaneció encerrado en el laboratorio hasta que pudo permitirse sacarlo de ahí. L’enfant secret es un filme que debería pertenecer a todas las filmotecas del mundo porque, simplemente, me parece que es uno de los más extraordinarios y monumentales trabajos de la historia del cine.

Traducción del inglés: Cristina Álvarez López (con la colaboración del autor)

(1)↑ Este ensayo está dedicado a Fergus Daly, que organizó el memorable e inaugural evento Garrel éternel en el Irish Film Centre.

(2)↑ Philippe Garrel y Thomas Lescure, Une caméra à la place du coeur (Provence: Admiranda/Insititut de l’image, 1992), pág. 83.

(3)↑ Ver, por ejemplo, la maravillosa entrevista realizada por Stéphane Delorme y Nicolas Azalbert, Cahiers du cinéma 671 (octubre, 2011), pág. 73.

(4)↑ Para una excelente introducción al trabajo de los setenta, ver el artículo de Stéphane Delorme “Désacord majeur. (Quatre films de Philippe Garrel)”, en Nicole Brenez y Christian Lebrat (eds), Jeune, dure et pure! Une histoire du cinéma d’avant garde et expérimental en France (Paris: Mazzota/Cinémathèque Française, 2001), págs. 311-4.

(5)↑ Alain Philippon, “L’amour en fuite”, Cahiers du cinéma 472 (octubre, 1993), pág. 31.

(6)↑ Tal y como David Ehrenstein apunta, “cada uno [de estos títulos] serviría para un filme anterior de Garrel”. Film – The Front Line 1984 (Denver: Arden, 1984), pág. 80.

(7)↑ Raymond Bellour, “Pour Sombre”, Trafic 28 (Hiver, 1998), pág. 8.

(8)↑ Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), pág. 200.

(9)↑ Alain Philippon, “L’enfant-cinema”, Cahiers du cinéma 344 (February 1983), pág. 31.

(10)↑ Une camera à la place du coeur, pág. 95.

(11)↑ Thierry Jousse, “Garrel: là où la parole devient geste”, en Jacques Aumont (ed.), L’image et la parole (Paris: Cinémathèque Française, 1999), pág. 199.

Garden of Stone: L’enfant secret (Philippe Garrel, 1982)

Click aquí para la versión en español

Finally getting to see L’Enfant secret (1982) as part of the Philippe Garrel conference in Dublin in June 2001 (1)↓ resolved a dilemma for me. I had been in love with this director’s work since the single – and, for me, momentous – Melbourne screening of Les Baisers de secours (1989) in 1994. A year later, after seeing J’entends plus la guitare (1991) and La Naissance de l’amour (1993), I was uncertain as to which to nominate as my favourite of his films: Baisers or Naissance.

Since that time, I have managed to see most of of Garrel’s entire output, working backwards to the earlier phases of his work in the ‘60s and ‘70s. All of the films are fascinating and many (including Liberté, la nuit [1983], Le Lit de vierge [1969] and Rue Fontaine [1984]) are tremendous, with J’entends plus la guitare rising in my estimation over time. I had always been keen to see L’Enfant secret – the film that, as every loyal Garrelian knows, marks the beginning of his narrative period, and the recommencement of the autobiographical project left behind after his first short, Les Enfants désaccordés (1964) – but I had no idea how overwhelming or extraordinary the experience would turn out to be. L’Enfant secret is in every sense the central film of Garrel’s career. It is also, in my view, incontestably his best.

Intensity is a quality I value in cinema, almost supremely. L’Enfant secret is a relentlessly and incomparably intense film, with a remarkably sustained, oceanic level of emotion. Of all Garrel’s autobiographical works since 1982, it is the one that seems to hold closest and most directly to the outline of events in his life. Where his alter ego figure in later films will transmute from theatre director to writer to painter to architect, here Jean-Baptiste (Henri de Maublanc) is a filmmaker. Only, perhaps, in the casting of Anne Wiazemsky as Elli (the Nico figure) – Garrel called her a “French princess playing a German worker” – do we see the first sign of the director’s creative, multi-faceted exploration of casting (as Fabien Boully has suggested, Garrel’s cinema is truly an art of casting), and his sense of the fictive possibilities of the auto-portrait roman (‘novel’) form . (Stoking this atmosphere of the Romanesque is the very title, derived no doubt from life, but also from a Juliette Greco song.)

The film traces a line of events from the first meeting of Jean-Baptiste and Elli in a communal household and an idyllic period of love, through to a separation that precipitates a period of drug-induced psychosis for Jean-Baptiste and then incarceration in a hospital where he undergoes electro-shock treatment. The lovers are subsequently reunited, but the death of Elli’s mother sends her into a depressive spiral that leads to heroin addiction. The secret child of the title is Elli’s; alluding to Nico’s son by Alain Delon, Garrel explains that “she had a child with a celebrated actor who would not recognise him” (2)↓. (Note the different selections and emphases Garrel makes for each discontinuous slice of his autobiographical roman: he largely conserved his memories of the May ’68 experience, for instance, for the magisterial Les amants réguliers [2005].)

Where Jean-Baptiste, as incarnated by the Bressonian model de Maublanc, is the most strikingly sunken, heavy-set and morose of the director’s stand-ins, Elli is an extremely complex, enigmatic and moving figure. In Garrel’s cinema the trauma of a grown-up person having to finally confront the symbolic order of adulthood (and parenthood) after suffering the death of a beloved parent tends to be mainly a male story (I think, principally, of Le Cœur fantôme [1996]) – if only because masculine problems are the ones with which Garrel is most familiar (despite his proud boast, increasingly over the past decade, that he ‘turns his control over’ for scenes written and scripted by women (3)↓). L’Enfant secret is the striking exception to this rule. The part of the story devoted to Elli’s grief over the sudden death of her mother, and the cataclysmic effect this has on her future development, is powerfully felt. Wiazemsky’s chanting of “maman”, in one of Garrel’s ubiquitous train scenes, is lacerating, like the son who cries “papa” in La Naissance de l’amour. Intriguingly, this aspect of the Nico story (assuming it is indeed based on real life) is filtered out of J’entends plus la guitare which, in content if not form, is the film closest to L’Enfant secret in Garrel’s career.

Talking of the characters in this way – and one should never deny the flesh-and-blood reality of the people in Garrel’s work, nor the acute psychological and behavioural observation he brings to his storytelling – runs the risk of erasing the special quality of L’Enfant secret. It is in many ways an iconic movie, made up solely of compressed, vivid high points – the kind of film that many dream of making but so few succeed in shaping. The characters are not given a conventionally psychological treatment, yet nor are they the grave emblems, set within the geometry of their intersecting solitudes, that we find in Le vent de la nuit (1999). What matters to Garrel in L’Enfant secret are the pure flashes of intersubjective states – union and separation, despair and derangement, ecstatic loss of self and hellish, immobile confinement. Although the film is essentially linear, its only essential driving logic is one of stark contradiction between one scene and the next: nothing and no one remains static or unified for very long. Bed scenes, which are a central motif of Garrel’s cinema, are here already used to conjure this entire kaleidoscope of situations, tensions and sensations.

When I suggested above that L’Enfant secret is in every sense the central film of Garrel’s career, I mean that firstly in its chronological and descriptive senses. The film stands at the cusp between what is, at present, the two halves of his oeuvre. It inaugurates the narrative period, but is itself only minimally and tenuously a narrative – it takes two main characters through from point A to B, but that’s about all. One could rightly say that it is simultaneously a fiction and a portrait film, the jewel in the crown of the series of works done in the ‘70s (including the remarkable Les Hautes solitudes [1974]) (4) ↓. The work on attenuated duration – or, in Alain Philippon’s more precise words, “the alternation of accelerations and decelerations, ruptures and open stretches” (5)↓ that marks all of his work from the portrait-films on – comes to be focused, in L’Enfant secret, on intersubjective looks, embraces, frozen (sometimes inscrutable) moments of tension. (In Les Hautes solitudes, that intersubjectivity exists, but its line runs from the subject in front of the camera to Garrel, the hand-holding operator, behind it. In L’Enfant secret, Elli will accuse Jean-Baptiste, in the aftermath of a painful love scene, of having “a camera where your heart should be”). One also sees now, looking back at the ‘70s work, how certain key Garrelian motifs and hyper-charged images – such as sleeping, walking, or a woman leaning against a window – pass directly from the portrait-films (where they are generated as spontaneous, documentary, primary evidence) to the fictions.

At the giddy height of this portraiture, there is no passage in Garrel’s cinema more divine or heartbreaking in its eternal stillness and internal repetition than the one about fifteen minutes into L’Enfant secret, where Jean-Baptiste and Elli are locked in a nocturnal embrace in the street, seemingly unable to say goodbye, but somehow forced to separate. The entire push-and-pull intensity of the film is concentrated in that precious combination of images, gestures and music.

At the same time, L’Enfant secret returns to Garrel’s work of the ‘60s – but in a ghostly way, picking up its distant echoes. Where the director’s ‘70s phase inaugurates an arte povera, his ‘60s work – the Zanzibar period – is (at least in an avant-garde context) rich, luxurious, expansive, a time of dandy aestheticism. It throbs with a counter-cultural sense of timeless myth, ritual and magic (extended in the films directed by Garrel’s collaborator, Pierre Clémenti), often centred around Holy Family imagery. In L’Enfant secret, the trio of mother, father and child has fallen to earth, and is more internally fraught and split than in even Le Révélateur (1968). It is essentially the intertitles that divide the film (not without mystery) into its parts – “The Caesarean Section”, “The Ophidian [i.e. snake] Circle”, “Last of the Warriors”, “The Disenchanted Forests” – which bring back traces of the ‘60s vision (6)↓. The richness of L’Enfant secret derives from a tension between the heightened poetry that these titles (perhaps also reflecting Nico’s song lyrics) massage – nature-based imagery of birth, danger, idyll, night/day cycles, weather, the animal kingdom – and the small, even tawdry lives and events related.

Raymond Bellour was astute to yoke the memory of L’Enfant secret to the currency of Philippe Grandrieux’s Sombre (1998): “… not since Philippe Garrel’s L’Enfant Secret has one seen, from a still young director, such a new and cutting-edge film in French cinema” (7)↓. There is much that links the films – from a view of emotions and experience that is clearly marked by a psychoanalytically-influenced understanding of the essential human drives (in both films, the scene of a small child viewing a movie, as if the first time, is truly primal) and a subtle but crucial reference to the realm of the fairy tale (stronger in Grandrieux’s film than Garrel’s) to an astonishingly intricate exploration of a range of conventionally forbidden techniques. These techniques include: extreme light and darkness (via photographic over- and under-exposure); an early-cinema preference for silence, music and noise over dialogue; and out-of-focus blurring (there needs to be a filmic history of blur written, at the very least to redeem it from the current modish use of the device in ads and rock video).

L’Enfant Secret seems to me to go even further than Sombre. The formal inventiveness of Garrel’s film is prodigious: image-flares, repeated shots, black frames, refilming off a moviola, shooting through various kinds of glass surfaces, startling compositional decentring (one of its most beautiful shots gives us a peek of tiny eyes without a face through the abundant leaves on a tree). Some scenes begin suddenly, shockingly, with the film taking flight into a hitherto unfamiliar stratosphere: the moments where Jean-Baptiste violently smashes a window, or Elli attempts to hurl herself out a window; or two men dragging Jean-Baptiste by force into the clinic, as his disembodied voice is heard on the soundtrack uttering a single word: “Resist”. This is the most extremely dissipative and disintegrative of Garrel’s works.

The effect of all this is startling, sometimes bewildering, offering a hyper-charged flow to which one ultimately must simply surrender – few films suspend the apprehension of real time like this one. One appreciates better the poetic oddities of Liberté, la nuit – especially its Godardian duality of tender lyricism and violent abruptness – having seen the film that precedes and prepares the way for it; but Liberté, for all its qualities, is already a step towards the cleaner arthouse style that Garrel will adopt fully only in Le Vent de la nuit – and temporarily, as it turned out, in the light of Sauvage Innocence (2001) and La frontière de l’aube (2008).

L’Enfant secret, by contrast, brings us very close to a dream-image that has long animated a certain discussion of cinema, especially experimental, animated, underground and Super 8 cinema: the idea that certain works, certain forms, can take us close to the ‘unconscious of film’ itself, a severe, primal, baroque place where language (of whatever kind) is still piecing itself together in the maelstrom of pre-signification, all the drives are superimposed in their impersonal intensity, and the very materiality of the cinematic medium is exposed at its rawest nerve-ends. Garrel’s radical work on flicker-effects and exposure ignites this dream, as does the presence of camera noise, which is such an integral part of the film’s texture – one really feels that one is attending, like a midwife, the birth of cinema.

On another level of heterogeneity, there is the dazzling music by Faton Cahen and Didier Lockwood. I have always been impressed by Garrel’s use of music as gesture, the way he emphasises the act of its precise placement by isolating it or delaying its entrance. But L’Enfant secret offers his boldest gesture of this kind. The first ten minutes or so of the film are completely silent, until that amazing music floods in, soaring for long passages. In a game that will reappear in a softer and more lyrical mode in Les Baisers de secours, music and dialogue at one point compete for aural dominance, weaving and fading in and out of each other as the characters walk.

Experiencing the shock of L’Enfant secret, I came to appreciate the significance of a certain, intractable experience of Otherness or alterity in his cinema. This stark presence of the other takes many forms in Garrel’s work; his mastery of these levels of ambiguity and strangeness is an overlooked aspect of his gifts as a director. There is the shock of people whom his characters encounter, particularly children, like the first view of Marianne’s secret child in J’entends plus la guitare. There is the matter-of-fact but fascinatingly deformed shape of a face in the same film. There are mysterious events that unfold, magically, before us (this is the Dreyer side of Garrel), like the instant togetherness of a new couple in La Naissance de l’amour, or a man waiting for his own death to arrive in Le vent de la nuit, or the pregnant complicity between Duval and Deneuve in the same film (there is a sense that they have met before – the haunted or shadowed encounter, a Blanchot theme dear to Garrel). There are the sidebar stories (usually accompanied by a surprising voice-over) which enter in a flurry and exit just as quickly: Mathieu finding the earring in Baisers, Marcus spying on his wife in Naissance. There are the written notes (voiced on the soundtrack in a spectral reading) or the phone calls (no less spectral in their intricate figuration of presence and absence), almost always harbingers of death, loss or disaster in Garrel (as in Rue Fontaine [1984]). There are his marvellous, poetic titles (phantom heart, secret child, emergency kisses, birth, wind, night), a mélange of Breton and Poe, so rich and strange…

There are otherly apparitions in Garrel. Psychosis: Jean-Baptiste sitting up in bed in a military outfit. Some visions are frank and base – Marianne pissing, Alcaïs menstruating – and others are obscene, like the hypodermic syringes that appear in the bathroom in L’Enfant secret, discarded on the floor in J’entends plus and especially the one found beside the young child in Le Cœur fantôme (a disturbing moment that Dowd rightly sees as central to Garrel’s work). There are also, in this family of apparitions, Garrel’s own odd, exclamatory insertions, such as the graphic signs whose words point over-obviously to the scenes they frame in Baisers (the final ‘alarm’ sign on the métro platform) and Le Vent de la nuit (the Durex ad that closes over Duval in the chemist as Deneuve watches and smiles). Finally, there is material that goes beyond the merely cryptic into the outrightly unassimilable or incommensurable (as the other must always, primally and ultimately, be in philosophic terms).

It is easy to forget or censor the moments in Garrel that come from nowhere, and receive no explanation other than the fact that he has chosen, for secret reasons, to put them there, like the drawing that begins Liberté, la nuit. Garrel’s films sometimes start with either a prolegomena (as in Le Vent de la nuit) or a swerve (as in the portrait study of the prostitute at the start of Le cœur fantôme) – Baisers is exceptional, by contrast, by plunging us into the fiction in its first gesture and line, Sy’s “Why am I not in the film?”. The opening of L’Enfant secret is extreme in seeming to start in another film altogether, a silent film of teenage love (it is hard to avoid the speculation that these figures are, symbolically, the main characters in a mystical, younger incarnation). This gaze upon another couple who will not be the subject of the rest of the film is part of the autobiographical reference to Garrel’s years in Positano (where two couples co-habited) – it returns as material in both J’entends plus and most recently Un été brûlant (2011), which is dedicated to the memory of his painter and close friend Frédéric Pardo – but it is also an emblem of the essential form of his work, breathtaking and disconcerting, beautiful and chilling in equal measure, like a disenchanted forest or a garden of stone.

One device recurring throughout L’Enfant secret is particularly captivating – the refilmed imagery of Elli’s child, stopping, starting, freezing, flickering. The haunting power of these images is impossible to describe. Partly this is a matter of theme: more brutally than in any other Garrel film, this child simultaneously incarnates the troublesome other who drives adult lovers apart (as in the almost comic scene where they cannot sleep together in the kid’s presence), and the lost boy who is inevitably and hopelessly abandoned by his biological guardians in this cruellest of worlds (this is where Garrel meets the Cassavetes of Love Streams [1984]). On another level, the refilmed imagery of the child provides a gateway into the deepest level of the filmic unconscious. Using a trick that may have already been becoming clichéd and hackneyed in the late ‘70s, Garrel sets in train a film within the film – directed by Jean-Baptiste and starring (it seems) Elli and her child; at one point he describes a project (called “The Disenchanted Forests”) which was one that, in reality, Garrel planned but abandoned.

But, as usual, Garrel gives us only the barest bones of this fictional conceit. What matters is the radical, contagious confusion in status this film-within causes to every single image in L’Enfant secret. In a giddily surreal sequence, the central trio go to a movie theatre to see a silent comedy; Garrel passes from a shot of them in their seats to the hall plunged into darkness and traversed by an odd light-play, as talk continues and rinky-tink screen music begins. Soon, we will see images of the threesome, accompanied by the same music, as if they were themselves the image on that screen. And from that point, literally anything goes: a repeated shot (separated by black frames) of Wiazemsky at a window – is that Garrel’s rushes, or Jean-Baptiste’s? This is not meant to be a solvable puzzle (as films-within-films so often are); rather, it opens forcibly the domain of cinema as a realm of indecidable mental images, neither entirely subjective nor objective. In this film which is so militantly concerned with states of mind – from depression to hallucination – we can no longer draw the dividing line between real shots, fabricated shots, and inner picturings. Nor can we easily draw a line between the film in its finished state (although that is surely what we are watching) and the many in-process, experimental layers of its ragged, driven, swirling incompletion.

These qualities come to effect the very constitution of the story and its nominal verisimilitude (a pathetically inadequate word in the context of this film): are those painterly smears of blood in Jean-Baptiste’s bath and bed evidence of actual suicide attempts, or something altogether more conceptual? Genre (another weak word in the context) also becomes impossible to fix: for a while, in the electro-shock scenes that are both serene and terrifying, L’Enfant secret becomes the most mysterious Val Lewton production ever made.

Reading about L’Enfant secret all these years, I had preserved a special memory of two particular citations. In The Time-Image, Gilles Deleuze describes (in the course of a magisterial few pages on Garrel) the moment in the film where “we see the café window, the man with his back turned, and, in the window, the image of the woman also from the back crossing the street and going to meet the dealer” (8)↓. At the time of the film’s first release in Paris, Alain Philippon (an extremely gifted critic who died in 1998) concluded his review thus: “I know few films, today, in which the simple shot of a man’s hand in a woman’s hair could carry an emotional charge of such intensity” (9)↓. I spent years imagining, dreaming these two screen moments! There was no way for me to know that both are, in fact, part of the same sequence-shot – and that this shot is in fact the ending of the film.

Garrel comments respectfully but matter-of-factly on Deleuze’s analysis of the shot in question: “One can naturally interpret this way of doubling Elli into two images, real and virtual, but objectively the reason for this was the poverty of resources: I had to film through a window to avoid yet more camera noise…” (the scene uses focal shifts in relation to this reflective surface that, in the context of the whole film, register as virtuosic). Garrel adds: “Always, when I shoot, I’m solely preoccupied with technical problems” (10)↓.

Garrel is too modest, because this is one of the most shattering endings to a movie I have ever seen, with a masterly sense of dramatically accumulating duration. It leaves the story at a completely unresolved moment: Jean-Baptiste now knows of Elli’s addiction and she knows he knows, so they have merely reached a moment that is both impasse and mutual exhaustion. She collapses onto his hand, kissing it sweetly but desperately (a little as Catherine Deneuve will smother her lover’s hands with kisses in Le Vent de la nuit), he strokes her hair in brutal silence, she says over and over, “don’t lecture me…”. And then the lights go up; there are no credits (neither at the start nor the end, beyond the title and intertitles), not even a black screen. This is one Garrel film in which his alter ego does not get that fragile island of fleeting, intersubjective redemption; there is no saving angel, no rebirth of love with another woman. Thierry Jousse sees it as a film “traversed by a sort of fatigue, in the sense that Blanchot speaks of fatigue as a constitutive element of a certain type of modern literature, or Deleuze describes Antonioni as the filmmaker who inscribed fatigue in bodies” (11)↓. There is existential weariness in the film, yes, but also an incredible sense of artistic renewal and inventiveness; and a solemn, ultimately sublime bearing witness to interior experience.

I am keen to find out how many prints of L’Enfant secret exist in the world, and what state the negative is in. Garrel, who was his own producer on the project, still needs to give special permission for its rare screenings; and a briefly available Japanese DVD release is now a true rarity. Never in my life have I been so seized, during the projection of a film, by a desire to protect and preserve it. I was struck by an intimate sense of the fragility of the celluloid itself, as even its birth pains carried this same aura: according to Garrel, it was completed in 1979 and remained locked up in the lab until he could afford to get it out. L’Enfant secret is a film that should belong to every Cinémathèque of the world, because – quite simply – it seems to me one of the greatest and most monumental works in cinema history.

(1)↑ This essay is dedicated to Fergus Daly, who organised the memorable and groundbreaking Garrel éternel event at the Irish Film Centre.

(2)↑ Philippe Garrel and Thomas Lescure, Une caméra à la place du cœur (Provence: Admiranda/Institut de l’image, 1992), p. 83.

(3)↑ See, for example, the splendid interview by Stéphane Delorme and Nicolas Azalbert, Cahiers du cinéma 671 (October 2011), p. 73.

(4)↑ For an excellent account of the ‘70s work, see Stéphane Delorme, “Désaccord majeur. (Quatre films de Philippe Garrel)”, in Nicole Brenez and Christian Lebrat (eds), Jeune, dure et pure! Une histoire du cinéma d’avant garde et expérimental en France (Paris: Mazzotta/Cinémathèque Française, 2001), pp. 311-4.

(5)↑ Alain Philippon, “L’amour en fuite”, Cahiers du cinéma 472 (October 1993), p. 31.

(6)↑ As David Ehrenstein notes, “Any one of [these titles] would serve for an earlier Garrel film”. Film – The Front Line 1984 (Denver: Arden, 1984), p. 80.

(7)↑ Raymond Bellour, “Pour Sombre”, Trafic 28 (Hiver 1998), p. 8.

(8)↑ Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), p. 200.

(9)↑ Alain Philippon, “L’Enfant-cinéma”, Cahiers du cinéma 344 (February 1983), p. 31.

(10)↑ Une caméra à la place du cœur, p. 95.

(11)↑ Thierry Jousse, “Garrel: là où la parole devient geste”, in Jacques Aumont (ed.), L’image et la parole (Paris: Cinémathèque Française, 1999), p. 199.

Original text © Adrian Martin July 2001/November 2011. Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López Diciembre 2011