Mamma Roma / L’automobile / Roma

La bal(l)ade de Anna Magnani

Click here for the English version

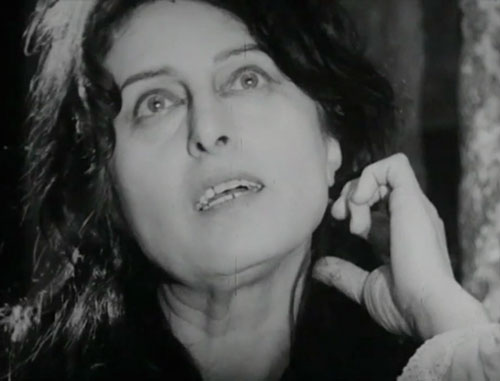

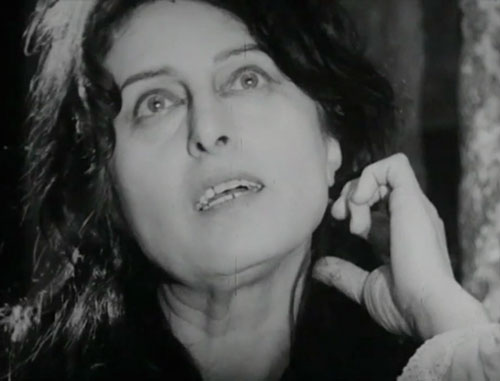

Anna Magnani suele ser descrita como la antidiva del cine italiano (1)↓. Pero ¿qué significa eso exactamente? ¿Una terrenalidad que contrasta con el glamour imposible de algunas de sus contemporáneas de Hollywood (y de Italia)? En su ensayo sobre Bellíssima (Bellissima, Luchino Visconti, 1951), Zadie Smith propone que “al igual que [Bette] Davies y [Joan] Crawford, Magnani es una belleza no convencional. A diferencia de ellas, Magnani es hermosa sin necesidad de cosméticos y, además, sin ningún interés en lo cosmético” (2)↓.

Podemos decir que, tanto en Roma, ciudad abierta (Roma città aperta, Roberto Rossellini, 1945) —con la que obtuvo el reconocimiento internacional— como en la mayoría de sus filmes, Anna Magnani es la mujer en la calle; pero en algunos títulos de su filmografía ella es, también, la mujer de la calle: la prostituta. Su conexión con los paseos urbanos, en todas sus variantes, es pues particularmente poderosa. Magnani, Roma y el acto de andar son convocados, en este ensayo audiovisual, a partir de tres filmes: Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962), L’automobile (Alfredo Giannetti, 1971) y Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972). En los dos primeros, Magnani interpreta a una prostituta; en el tercero, se interpreta a sí misma (en la que sería su última aparición cinematográfica antes de su muerte en septiembre de 1973).

Las películas de Pasolini y Fellini son muy conocidas, en cambio no se ha escrito demasiado sobre L’automobile, un filme para televisión que forma parte de un ambicioso proyecto de Giannetti —quien había ganado un Oscar por el guión que coescribió para Divorcio a la italiana (Divorzio all’italiana, Pietro Germi, 1961)—. Giannetti quería realizar seis filmes ambientados en distintos periodos históricos, todos ellos con Magnani en los papeles de “seis mujeres que lucharon, sufrieron y perdieron” (3)↓. Finalmente, la actriz solo pudo intervenir en cuatro de estas películas, tres de las cuales —La sciantosa (1971), 1943: Un incontro (1971) y L’automobile— terminarían siendo conocidas como la trilogía “Tres Mujeres” (4)↓. L’automobile cuenta la historia de una prostituta de mediana edad, Anna Mastronardi (conocida como La Condesa), que pone todos sus esfuerzos en comprar un coche que le permitirá adquirir una mayor independencia. En el filme de Pasolini, la epónima Mamma Roma se reúne con su descarriado hijo adolescente, Ettore (Ettore Garofalo), y busca también un modo de abandonar la prostitución.

El título y la estructura de mi pieza provienen, en parte, de los escritos de Gilles Deleuze. En La imagen-movimiento: Estudios sobre cine 1, él hace un juego de palabras entre paseo (balade) y balada (ballade), y escribe sobre una nueva forma de paseo urbano en el cine de después de la guerra. El “vagabundeo moderno” tiene lugar, según Deleuze, en “el tejido desdiferenciado de la ciudad, en contraste con la acción que casi siempre se desenvolvía en los espacios-tiempos cualificados del viejo realismo” (5)↓. Deleuze hace referencia a un comentario de John Cassavetes quien, una vez, dijo que “se trata de deshacer el espacio, no menos que la historia, la intriga o la acción” (6)↓. Los tres filmes que he utilizado en mi pieza audiovisual se sitúan en Roma, pero en ellos apenas vemos lugares emblemáticos de la ciudad eterna. El espectador está con Magnani a ras de suelo: una decisión formal ligada a esa terrenalidad tan característica de la actriz.

Frédéric Gros escribe: “A fuerza de apoyarse en la tierra, de sentir su gravedad, de descansar en ella a cada paso, andar es como una inspiración consciente de energía” (7)↓. Hay, sin duda, mucho ánimo y energía en los paseos de Magnani (algo que la diferencia de algunos de los personajes que Deleuze tiene en mente). Lo vemos en el primer encuentro con su hijo en Mamma Roma, así como en el plano secuencia nocturno donde camina las calles por última vez, contando la historia de su vida (esta escena parece ser también un ejemplo perfecto de ese “deshacer el espacio” del que hablaba Cassavetes). En los compases iniciales de L’automobile, el andar de Magnani es igual de enérgico; de nuevo, más que en aquello que rodea al personaje, Giannetti está interesado en la forma en que La Condesa negocia con el paisaje callejero.

Pese a la energía y a la vitalidad de los paseos de Magnani en Mamma Roma y L’automobile, los filmes no tienen un desenlace feliz. Sin embargo, su conmovedora aparición final en Roma captura a la perfección el espíritu indomable de la antidiva italiana:

Fellini: En cierto modo, ella es un símbolo de la ciudad misma.

Magnani: ¿Qué es lo que soy?

Fellini: Roma: loba y virgen vestal, noble y pescadera, sombría y festiva. Y así podría continuar hasta mañana…

Magnani: ¡Vete a casa y duerme un poco, Federico!

Fellini: ¿Puedo preguntarte algo?

Magnani: No, no me fío de ti. ¡Adiós! ¡Buenas noches!

Traducción al español: Cristina Álvarez López

Texto original © Pasquale Iannone, enero 2015 | Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, enero 2015

↑(1) Ver, entre otros, HOCHKOFLER, Matilde: Anna Magnani: Lo spettacolo della vita (Roma: Bulzoni, 2005).

↑(2) SMITH, Zadie: “Notes on Bellissima”, en Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2009), pág. 175.

↑(3) GOVERNI, Giancarlo: Il romanzo di Anna Magnani (Roma: Minimum Fax, 2008), pág. 181.

↑(4) Magnani y Giannetti realizaron, junto a Marcello Mastroianni, un cuarto filme —Correva l’anno di grazia 1870— estrenado a finales de 1971.

↑(5) DELEUZE, Gilles: La imagen-movimiento: Estudios sobre cine 1 (Barcelona: Paidós, 1994), pág. 289.

↑(6) Ibídem, pág. 212.

↑(7) GROS, Frédéric: Andar, una filosofía (Barcelona: Taurus, 2014).

![]()

The Bal(l)ade of Anna Magnani

Click aquí para la versión en español

Anna Magnani is often described as the ‘anti-diva’ of Italian cinema (1)↓. But what exactly does that mean? Her ‘down-to-earthness’ as opposed to the impossible glamour of some of her Hollywood (and Italian) contemporaries? In her essay on Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima (1951), Zadie Smith argues that “like [Bette] Davis and [Joan] Crawford, Magnani is an unconventional beauty. Unlike them, she is beautiful without any cosmetic effort whatsoever, and moreover, without any interest in the cosmetic” (2)↓.

In her international breakthrough Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945), and indeed in the majority of her films, Magnani can be said to be the woman in the street, but in several titles in her filmography she is also the woman of the street – the prostitute. Her connection with urban walking, in all its different forms, is therefore particularly strong. In this audiovisual essay, I bring together Magnani, Rome and the walk by looking at three films: Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962), L’automobile (Alfredo Giannetti, 1971) and Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972). In the first two, Magnani plays the character of a prostitute, while in the third she plays herself in what turned out to be her final screen appearance before her death in September 1973.

The Pasolini and Fellini films are, of course, very familiar; but less has been written about L’automobile, a TV film that was part of an ambitious project by Giannetti, an Oscar winner for his co-written screenplay for Pietro Germi’s Divorce Italian Style (1961). He intended to make six films set in different time periods, all featuring Magnani in the title roles of “six women who had fought, suffered and lost” (3)↓. In the end, Magnani only managed to make four of these, three of which became known as the ‘Three Women’ trilogy: La sciantosa, 1943: Un incontro and L’automobile (4)↓. The last of these tells the story of middle-aged prostitute Anna Mastronardi (aka ‘The Countess’), who sets her heart on buying a car to gain a greater sense of independence. Magnani’s eponymous Mamma Roma is reunited with her wayward teenage son Ettore (Ettore Garofalo) and is also looking for a way out of prostitution.

The title and structure of my piece was informed partly by the writings of Gilles Deleuze who, in Cinema 1, makes a pun out of the French words for stroll (balade) and ballad (ballade) and talks of a new form of urban journey in the cinema of the post-war period. The “modern voyage” according to Deleuze, takes place in the “undifferentiated fabric of the city – in opposition to action which often unfolded in the qualified space-time of the old realism” (5)↓. Deleuze references a remark by John Cassavetes who once said that it is “a question of undoing space, as well as the story, the plot or the action” (6)↓. While all three of the films I feature are set in Rome, we get very few of the Eternal City’s familiar landmarks. The viewer is on ground level with Magnani – a formal choice which ties in to her trademark earthiness.

“Walking, by virtue of having the earth’s support”, says Frédéric Gros, “feeling its gravity, resting on it with every step, is very like a conscious breathing in of energy” (7)↓. There is indeed great energy and spirit in Magnani’s walks here (setting her apart from some of the characters Deleuze has in mind). We see it in her first encounter with her son in Mamma Roma or the single-take nocturnal sequence in the same film where her character walks the streets one final time and recounts the story of her life (this scene also seems to be a perfect example of the ‘undoing of space’ mentioned by Cassavetes). In the opening scenes of L’automobile, Magnani’s walking is just as energetic; again, Giannetti’s interest is less in the surroundings and more on Magnani’s Contessa and the way she negotiates the streetscape.

Despite the energy and zest of Magnani’s walks in Mamma Roma and L’automobile, the films themselves do not end happily. However, her final, poignant appearance in Roma perfectly captures the indomitable spirit of Italy’s ‘anti-diva’:

Fellini: In a way, she’s a symbol of the city itself…

Magnani: What am I?

Fellini: Rome – she-wolf and vestal virgin, noblewoman and fishwife, sombre and festive. I could go on until tomorrow morning…

Magnani: You’d better go home and get some sleep, Federico!

Fellini: Can I ask you a question?

Magnani: No, I don’t trust you. Ciao! Goodnight!

© Pasquale Iannone, January 2015

↑(1) See, amongst others, HOCHKOFLER, Matilde: Anna Magnani: Lo spettacolo della vita (Roma: Bulzoni, 2005).

↑(2) SMITH, Zadie: “Notes on Bellissima”, in Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2009), p. 175.

↑(3) GOVERNI, Giancarlo: Il romanzo di Anna Magnani (Roma: Minimum Fax, 2008), p. 181.

↑(4) A fourth film, Correva l’anno di grazia 1870, was made by Magnani and Giannetti together with Marcello Mastroianni and released in late 1971.

↑(5) DELEUZE, Gilles: Cinema 1: The Movement-Image (London: Continuum, 2005), p. 212.

↑(6) Ibid., p. 212.

↑(7) GROS, Frédéric: A Philosophy of Walking (London: Verso, 2014), p. 105.