Nuit et jour

Pequeñas jugadas (#2)

Click here for the English versión

En un plano secuencia de La cautiva (La captive, 2000), Simon (Stanislas Merhar) se introduce de golpe en un encuadre estático y vacío, camina a lo largo de la fachada de un restaurante y, a través de la ventana frontal, ojea en su interior en busca de Ariane (Sylvie Testud), su novia ausente. Para poner en escena esta acción, Chantal Akerman usa un tipo de movimiento de cámara al que ha dado predilección con frecuencia: un travelling lateral que, durante la mayor parte del tiempo, mantiene al actor en el centro del encuadre mientras este se desplaza. El restaurante, hundido en la oscuridad, está a punto de cerrar. Simon entra —la cámara, en cambio, se detiene y no abandona su lugar en el exterior—, conversa con un camarero —las palabras no son importantes; en la banda de sonido escuchamos el ruido ambiente de los coches de los cuales solo vemos su reflejo en el cristal—, se da la vuelta y sale. Simon vuelve sobre sus pasos y la cámara empieza a desplazarse de nuevo, recorriendo el mismo itinerario que antes. Pero, en el instante preciso en que Simon se da la vuelta, varios elementos de la escena se transforman por completo: el ritmo de su caminar se torna más lento, ahora realiza varias paradas y observa con más nerviosismo el espacio fuera de campo que lo rodea; la música de L’ile des morts de Rachmaninoff, que escuchamos en muchas ocasiones a lo largo del filme, empieza a sonar. Finalmente, en un reflejo perfecto del modo en que comenzaba este plano secuencia, la cámara se detiene por voluntad propia y el personaje sale del encuadre. Este momento cristalino de cine ha llegado a su fin.

En pantalla, dura solo un minuto; un minuto en el que Akerman nos hace sentir la pesadez del tiempo, del estado de ánimo del personaje, de la noche misma y de sus secretos. En la página de un guión, seguramente no equivaldría más que a una línea de texto (“Simon observa el restaurante, entra, sale…”). Y, aunque, en la memoria de los cinéfilos, se suele asociar a la cineasta belga con duraciones y distancias épicas —como las que cubre en muchas secuencias de D’Est (1993)—, los elementos de esta escena de La cautiva son modestos: el espacio cartografiado por la cámara es poco más que el de la fachada de un solo restaurante. Esto nos da una idea de uno de los aspectos esenciales del arte cinematográfico de Akerman (y, a menudo, uno poco reconocido o explorado): ella trabaja con pequeñas jugadas —tanto de los personajes como de la cámara—, con áreas reducidas de un territorio, con gestos mínimos. Algunos de los pasajes más intensos de La folie Almayer (2011) tienen lugar en zonas de vegetación, tierra o barro extremadamente restringidas, donde tanto la cámara como los actores se mueven lateralmente, yendo y viniendo a través de ese acotado pedazo geográfico. Y estas jugadas deben entenderse también en otro sentido, a otro nivel: como gestos realizados por el propio filme, con y sobre sus materiales formales.

Todo análisis apreciativo del trabajo de Akerman debería efectuar también sus pequeñas y minuciosas jugadas. Con este propósito, tomamos aquí un fragmento que tiene lugar, aproximadamente, en el minuto 56 de uno de sus mejores filmes, Nuit et jour (1991). El fragmento elegido dura menos de sesenta segundos y está compuesto por una escena completa, aunque breve (solo cinco planos), más el plano inicial de la escena posterior.

Nuit et jour tiene una premisa simple y encantadora, que podría ser la de una anécdota, una broma o un cuento de hadas: una mujer joven, Julie (Guilaine Londez), mantiene simultáneamente dos aventuras con dos hombres distintos, Jack (Thomas Langmann) y Joseph (François Négret), ambos taxistas. Uno trabaja de noche y el otro, de día. El filme apenas explota el melodrama o el suspense inherente a una trama de estas características; se trata, sobre todo, de un filme ambiental, atmosférico —uno que se deleita con la atmósfera de las emociones, libre (como La felicidad [Le bonheur, 1965] de Agnès Varda) de sentimientos morales de culpa o remordimiento por parte de Julie—.

La escena elegida (montada por Francine Sandberg, colaboradora habitual de Akerman) comienza con un plano fijo exterior. Vemos la puerta del edificio donde viven Jack y Julie y, enseguida, escuchamos el zumbido del sistema de apertura que desbloquea el cierre. Julie aparece primero y, después, un paso por detrás de ella, Jack. Ambos caminan en dirección a la cámara. Ella mira al frente, pero parece absorta en sus pensamientos. Él, en cambio, con la cabeza ladeada y con una expresión relajada pero inquisidora, no deja de observar a Julie que avanza con agilidad y decisión. De pronto, ella detiene el paso y Akerman introduce el siguiente plano, más cercano a la pareja, mediante lo que resulta ser (cuando lo inspeccionamos detalladamente) un sutil faux-raccord. Pero algo nos revela la elipsis, casi imperceptible, que ha acontecido aquí: al final del plano 1, la puerta por la que acababan de cruzar los personajes todavía tenía que recorrer unos centímetros para cerrarse por completo mientras, al inicio del plano 2, ese espacio vacío ya ha desaparecido (de hecho, lo que escuchamos justo después del corte es el click del cierre).

Inicio plano 1 / Final plano 1 / Plano 2

Esta elipsis de apenas un segundo marca la primera jugada de la escena —un gesto firme, una decisión tomada por el propio filme—. En este caso, una jugada oculta, escondida, que debemos desenterrar a partir de la observación de sus rastros visibles: Jack está ahora más cerca de Julie, casi en línea con ella; y, lo que es más importante, algo ha cambiado en la expresión facial de Julie. Cuando vemos la escena por primera vez, podemos sentir ese cambio porque deja una impresión en nosotros, pero no sabemos muy bien de dónde viene o qué lo provoca, y tampoco somos capaces de localizar su lugar exacto. Necesitamos observar atentamente el final del plano 1 y el principio del plano 2 para advertir que, en ese intervalo, el rostro de Julie está más ladeado y su mirada ya no es la misma: ahora ella parece más atenta y concentrada, con la vista fija en un punto concreto, como si hubiese divisado algo o reconociese a alguien. Esta epifanía, sin embargo, es extremadamente fugaz y resbaladiza ya que, en menos de un segundo, Akerman va a ejecutar su segunda jugada, un gesto con el que reorganiza, de nuevo, todo el tablero: Julie gira su cabeza hacia la izquierda y sus ojos se encuentran, frente a frente, con los de Jack.

Llegados a este punto, vale la pena que nos detengamos un momento en la humilde pero hermosa coreografía de los cuerpos dispuesta por Akerman a lo largo de estos dos planos. Sin que apenas nos hayamos dado cuenta, se ha producido aquí un pequeño pero significativo ajuste de distancias entre los personajes. Al principio, cuando ambos salen al exterior, Julie avanza casi por su cuenta, como si Jack no la acompañara —sensación acentuada por el hecho de que él no deja de mirarla, mientras ella, en cambio, solo mira al frente—. “Parecía estar muy lejos, en un mundo al cual él no podía acceder”, nos dice la voz en off en una escena anterior. Sin embargo, durante los ocho segundos que duran estos dos planos, Jack se las ingenia para acercarse cada vez más a Julie. Tras la elipsis, los dos se encuentran perfectamente alineados. Cuando, en el plano 2, ella ladea la cabeza para mirarlo, él gira su cuerpo hacia ella, como si ejecutara un paso de baile que responde con un bello eco al movimiento previo de Julie. De perfil, perfectamente posicionados en el centro del plano, ambos se miran durante dos segundos y Jack sonríe. Nada como esta danza discreta y poco ostentosa para apreciar cuán cuidadosa y receptiva es Akerman con los tiempos y los ritmos, con los pequeños movimientos y expresiones corporales sobre los que construye toda su puesta en escena.

Planos 1 y 2: reajustando las distancias

Estamos ante una directora profundamente musical y este fragmento es una excelente muestra de ello. Fijémonos, por ejemplo, en la sutileza de Akerman a la hora de introducir la pieza que sonará en esta escena, el Preludio de las Bachianas Brasileiras nº. 1 de Heitor Villa-Lobos —una composición que la cineasta volvería a utilizar en Romance en Nueva York (Un divan à New York, 1996)—. Si prestamos atención, nos damos cuenta de que el tema comienza a escucharse durante el plano 1, cuando los personajes salen al exterior; las primeras notas, sin embargo, son enmudecidas por el ruido del motor de un coche. Solo cuando el sonido del vehículo desaparece, percibimos con autonomía y claridad la composición de Villa-Lobos. Akerman evita todos los lugares comunes y malos hábitos a la hora de trabajar con la banda sonora (inundar las escenas con música, utilizarla como burdo subrayado dramático, abusar de ella y emplazarla caprichosamente en cada hueco del filme…). En lugar de eso, la cineasta arregla las cosas de forma que el propio sonido ambiental parece dar a luz la pieza musical y, luego, la pone a interactuar con todos los demás elementos cinematográficos. Como en Gabbeh (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996), esta es una escena donde todo canta, entretejiendo ese paisaje sonoro tan característico de Akerman que es como una especie de musique concrète.

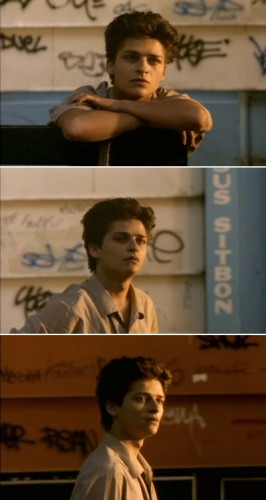

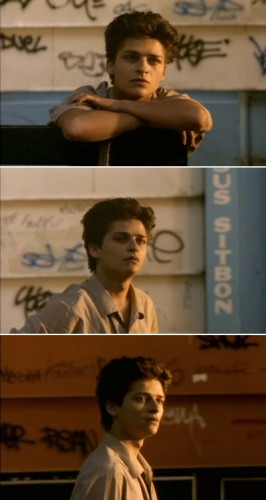

Para comprender el shock que nos provocará la jugada preparada por Akerman en el plano 3, es importante volver atrás y revisar ese trabajo con las repeticiones y las variaciones tan característico de su cine y, en concreto, de este filme. A lo largo de Nuit et jour hemos presenciado ya, en cuatro ocasiones, una escena similar a esta: Jack y Julie saliendo de casa. Unas veces, Akerman comienza mostrándonos a la pareja mientras baja por las escaleras; otras, decide iniciar la escena con el plano exterior de la puerta del edificio. Solo en una ocasión hemos visto a los personajes marcharse juntos, abrazados; pero, por lo general, los dos toman direcciones opuestas —Julie por la izquierda del encuadre, Jack por la derecha—. Sin embargo, aquí Akerman introduce algo totalmente imprevisible, la jugada más inesperada de la escena: un plano medio de Joseph, el amante nocturno de Julie, que está observando a la pareja desde el otro lado de la calle.

Plano 3

Sentado en un banco, con los brazos cruzados sobre el respaldo y la barbilla apoyada sobre estos, Joseph mira a Julie con una mezcla de tristeza e impotencia. Si bien Joseph sabe que ella mantiene otra relación amorosa, esta es la primera vez, desde que comenzaron su aventura, que la ve en compañía de Jack. Este plano es sostenido durante casi cuatro segundos, tiempo en el que podemos observar cómo los músculos del rostro de Joseph se destensan ligeramente, cómo la tirantez de sus labios se afloja mientras respira y traga saliva. Hay un detalle que es importante conocer para sopesar la magnitud de lo que estamos presenciando en estos pequeños gestos: la noche anterior Julie faltó, por primera vez, a su cita con Joseph. Por lo tanto, en este plano, el personaje masculino pasa de los nervios, la excitación y la incertidumbre de la espera a una devastación repentina provocada por la gravedad de esa visión inesperada.

La acción se detiene por completo, queda congelada por unos segundos en la quietud y el silencio. Ahora pasamos al plano 4, un close-up de Julie que constituye la jugada más intensa y grave de la escena. Se trata de un tipo de plano más típico de Scorsese que de Akerman: la cámara encuadra a Julie (con su característica y enigmática expresión de Mona Lisa) y, entonces, da un empujón hacia delante, acercándose un poco más a ella desde abajo. Un verdadero subrayado de la cámara-stylo de Akerman, un gesto estilístico que marca su propia identificación con (y deseo por) su protagonista femenina. Todavía congelada, Julie parpadea (un parpadeo maravillosamente dramático, perfectamente cronometrado) y, después, sonríe ligeramente, se gira de manera abrupta y se marcha sobre el sonido de sus tacones. Sentimos que se trata de un gesto decisivo. Pero, en esta historia, nosotros raramente sabemos qué ha decidido Julie, por qué o cuándo; ni siquiera en el magnífico plano secuencia final.

Plano 4

Algo verdaderamente extraño e inusual sucede en esta escena: tras el plano 2, Jack desaparece tanto literal como figuralmente. Suponemos que el personaje permanece fuera de campo, junto a Julie, hasta que ella se da la vuelta y se marcha. Sin embargo, no hay nada —ni una imagen, ni un sonido— que nos permita determinar con exactitud cuándo sucede esto o si realmente sucede: es como si la mirada de Joseph hubiese bloqueado a Jack y, por lo tanto, esto bastase para borrarlo del plano y de la escena. Si bien es cierto que Akerman casi nunca recurre al plano/contraplano convencional, aquí disfruta evocando algo que parece su simulacro. Los planos consecutivos de Joseph (plano 3) y Julie (plano 4) comparten una escala y un tono lumínico similares (la luz del atardecer usada prodigiosamente por el filme). Además, el segundo de ellos está tomado desde un ángulo contrapicado que se corresponde con la posición de Joseph. Akerman crea una continuidad imaginaria tan perfecta entre estos planos que, por un instante, todo lo que rodea a los personajes se desvanece. Julie y Joseph se quedan solos, aislados, en lo que parece ser un momento de intimidad compartida. Y nosotros, pese a saber que los personajes no se encuentran en realidad tan cerca el uno del otro, nos sumergimos de lleno en ese dulce espejismo.

Planos 3 y 4: creando un momento de intimidad compartida

La intensidad especial de este fragmento viene dada por la combinación entre los micromovimientos que lo componen y el poso de ambigüedad que deja en nosotros. En Nuit et jour Akerman nos obliga, constantemente, a volver a procesar lo que hemos visto y, con frecuencia, la percepción que teníamos de un plano es modificada o puesta en duda por el plano posterior. Esto es precisamente lo que sucede aquí y lo que otorga a este momento su enigmática y misteriosa aura. Como siempre, la emoción de la escena reside en su construcción por capas, en la mezcla, la suma y la sustracción. Este proceso de aligerar y espesar la escena tiene el efecto, directo y visceral, de hacer que el mundo ficcional parezca sombrío y pesado, o liviano y libre; más radicalmente, el paso de un determinado arreglo de los elementos formales a otro disuelve el mundo, o lo recrea, o nos devuelve bruscamente a él.

Aquí, la música juega un papel fundamental a la hora de provocar este tipo de transiciones dinámicas. Durante el cara a cara de Julie y Jack, la pieza de Villa-Lobos se eleva como el retumbar grave de las nubes que se reúnen antes de la tormenta. Gana intensidad y volumen cuando el sonido de los zapatos de Julie se desvanece en la distancia del fuera de campo. La principal línea melódica del violoncelo se impone en el siguiente plano (5), mientras Joseph se pone en pie y, con los ojos fijos en Julie, efectúa un desplazamiento lateral antes de desaparecer por la derecha del encuadre. Este plano funciona también devolviéndonos a la realidad: redescubriéndonos el papel de voyeur de Joseph y subrayando su distancia respecto a Julie (quien, en realidad, debe de estar ya bastante lejos cuando él comienza a caminar con su mirada clavada en ella: a Akerman, como a Godard, no le preocupa este tipo de irrealidad espacial). Es mediante esta jugada que comprendemos lo que hemos presenciado hace solo un instante: el plano de Julie se revela como una magnificación de ese momento en que Joseph ve, por primera vez, cómo ella le entrega su sonrisa a otro hombre. Aquí, tenemos un plano subjetivo en el sentido más profundo e íntimo del término: la cámara no ocupa el lugar de los ojos de Joseph, sino el lugar de su corazón.

Plano 5

En esta breve escena, Akerman ha transformado un gesto simple y mínimo —Julie y Jack girándose para mirarse, un tercer personaje observando esto— en un momento de intriga, increíble y misterioso, sostenido a lo largo de cinco planos distintos. Después, en un corte hermosísimo, Akerman nos ofrece una vista de Julie: sentada en un café, con el movimiento firme e implacable de sus ojos que se parece al de una cámara, sigue los pasos de Joseph que, fuera de campo, se acerca. Este momento es, en sí mismo, otra repetición/variación de algo que ya habíamos visto: anteriormente, era él quien la esperaba a ella en ese mismo lugar. Julie, simplemente, está sentada en la mesa de un café, pero es como si ella (y nosotros) estuviésemos en el paraíso: la música ha sustituido por completo al sonido ambiente y, pictóricamente, las luces desenfocadas de los coches forman una línea en el cristal que redefine y redibuja la realidad espacial —un llamativo ejemplo de la plasticidad del estilo de Akerman—. Y es como si todas esas cosas juntas (la música, las luces, la zona ingrávida, sus ojos) estuviesen atrayendo dulcemente a Joseph, atrayéndole al interior del encuadre, al interior de ese plano compartido por ambos.

Plano 6

Este paraíso, sin embargo, no puede y no va a durar: el leve bocinazo de un coche marca el retorno del sonido ambiente y da paso al diálogo atormentado y lleno de celos de la pareja. Pero antes del inicio de esta conversación, el filme ha grabado a fuego en nuestra mente el recuerdo especial de la sonrisa de Julie mientras, sentada en ese café, mira a través de la ventana: una sonrisa que es siempre la misma y siempre nueva, porque no espera nada, no anticipa nada, solo el momento presente de absoluta alegría del que participa.

© Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin, Octubre 2015

(*) Este texto fue publicado originalmente, en su traducción al francés, en Chantal Akerman, eds. Dominique Bax y Cyril Béghin (Bobigny: Magic Cinéma, 2014).

![]()

Small Moves (#2)

Clic aquí para la versión en español

In a plan-sèquence of La captive (2000), Simon (Stanislas Merhar) suddenly enters a briefly empty, static frame and walks the length of the façade of a restaurant, searching inside with his gaze, through the front window, for any sign of his absent girlfriend, Ariane (Sylvie Testud). To render this action, Chantal Akerman uses a type of camera movement she often favours: a lateral tracking that more or less keeps the actor in the centre of the frame as he walks. The restaurant has almost completely closed, and is already plunged into darkness. Simon enters (the camera halts, staying in its spot), talks to a waiter – the words are unimportant, the soundtrack stays with the ambient noise of cars passing, unseen except as reflections in the restaurant windows – then he turns and exits. He begins retracing his steps, and the camera moves back along its same previous path. But several elements of the scene have decisively transformed at the precise instant of his turn: Simon’s pace is much slower, with several halts and more agitated scanning of the off-screen space all around him; music (Rachmaninoff’s L’île des morts, often heard during the film) enters the sound mix. Finally, in an exact mirror of how the shot began, the camera stops of its own volition and the character exits the frame. This crystalline moment of cinema is over.

It amounts to just over one minute on screen, in which Akerman makes us feel the heaviness of time, of the character’s mood, of the night itself and its secrets. On the page of a screenplay, it would surely not amount to much more than: ‘Simon scans the restaurant, walks in, walks out’. And – although Akerman is often associated, in the memory of cinephiles, with epic durations and distances, such as those covered during many sequences of D’est (1993) – the elements of this scene in La captive are modest: the space mapped by the camera is little more than the front of a single restaurant. This cues us to an essential aspect of Akerman’s cinematic art, not often recognised or explored: she works with small moves (whether of characters or the camera), tiny patches of territory, minute gestures. Some of the most intensely dramatic passages of La folie Almayer (2011) take place in extremely reduced areas of greenery, sand or mud – with both camera and actors moving laterally back and forth across this pinched geographic wedge. And these moves must also be understood in another sense, on another level: as gestures performed by the film itself, on and with its formal materials.

Any appreciative analysis of Akerman’s work must also make its own, small, fine-grain moves. To this end, we take a very brief but complete scene – a sequence of five shots – plus the opening shot of the following scene, occurring 56 minutes into one of her finest films, Nuit et jour (1991): in total, running less than sixty seconds. The film has a simple, beguiling premise, such as might belong to an anecdote, a joke, or a fairy tale: a young woman, Julie (Guilaine Londez), is having simultaneous affairs with two guys, Jack (Thomas Langmann) and Joseph (François Négret), who both drive taxis: one drives by night, the other by day. The film barely exploits either the melodrama or the suspense inherent in such a plot; it is, above all, an ambient, atmospheric film – luxuriating in the atmosphere of emotions, free (like in Agnès Varda’s Le bonheur, 1965) of any moral guilt or remorse on Julie’s part.

The scene (edited by Francine Sandberg, Akerman’s frequent collaborator) begins with an exterior, static shot. We see the door of the building where Jack and Julie live, and then we hear the buzz of the door opener that will allow them to appear. Julie emerges first, then, a step behind her, Jack. They walk toward the camera. She looks ahead, but seems to be absorbed in her thoughts. He, on the other hand, with a tilted head and a relaxed but inquisitive expression, never stops observing Julie, who moves agilely and decisively. Suddenly she ceases advancing, and Akerman cuts to the second shot, closer in on the couple, in what turns out to be (on detailed inspection) a subtle faux-raccord. However, something explains the almost imperceptible ellipsis that has taken place here: at the end of shot 1, the door that the characters have just exited still has several inches left to close while, at the start of shot 2, this gap has disappeared (in fact, what we hear right after the cut is the click of the lock).

Start shot 1 / End shot 1 / Shot 2

This ellipsis of barely a second marks the first move of the scene – a bold gesture made, a decision taken, by the film itself. In this case, it is a hidden, secret move that we can intuit only from close observation of the visible traces: Jack is now closer to Julie, almost in line with her; and, more importantly, something in Julie’s facial expression has changed. When we watch the scene for the first time, we can feel this change because it has already made an impression on us, but we scarcely know from where it comes or what caused it, or how to pinpoint the effect. We need to pay strict attention to the end of shot 1 and the start of shot 2 to see that, in this interval, Julie’s head is pointed in a different direction, and her gaze is no longer the same: now she seems more attentive, concentrated, her eyes fixed on some specific point – as if she has spotted something or recognised someone. However, this epiphany is extremely fleeting and subtle because, in less than a second, Akerman launches her next move, a gesture that completely rearranges the chess board: Julie turns her head entirely around to face Jack’s eyes.

It is worth pausing here, for a moment, amidst the simple but beautiful choreography of bodies disposed by Akerman across these first two shots. With us hardly being aware of it, a small but significant adjustment of the distance between the characters has been made. At the start, when they hit the street, Julie moves almost as if alone, without Jack accompanying her – a sensation accentuated by that fact that he never takes his eyes off her, whereas she looks only before her. “She seemed far away, in a world he could not access”, says the voice-over (Akerman’s own) in a previous scene. However, in the eight seconds covered by these two shots, Jack does manage to get closer to Julie. After the ellipsis, the two are perfectly lined up with each other: when she turns her head to look at him, he turns his body toward her – as if executing a dance step that responds with a delicate echo of Julie’s prior movement. In profile, now perfectly positioned in the centre of the shot, they look at each other for two seconds, and Jack smiles. There is nothing better than this discreet, unobtrusive dance to show how detailed and responsive Akerman is to timing and rhythm – the small movements and bodily expressions upon which her mise en scène is entirely constructed.

Shots 1 and 2: readjusting the distances

So we are dealing with a profoundly musical director; this fragment offers an excellent demonstration of the fact. Notice, for instance, Akerman’s subtlety in introducing the musical piece that appears under the scene, the Prelude to Bachianas Brasileiras no. 1 by Heitor Villa-Lobos (a piece she would later re-use in A Couch in New York, 1996). If we listen attentively, we realise that this musical theme begins to be heard in shot 1, as the characters exit the door; its first notes are, however, obscured by car engine noises. Only when this car sound disappears can we perceive Villa-Lobos’ composition as a clear and autonomous element. Akerman eschews all the usual clichés when working on her soundtracks; she avoids the bad habits that are so ubiquitous elsewhere (flooding scenes with music, placing it absolutely everywhere, using it to underline dramatic moments…). Instead, she arranges things so that the captured, ambient sound gives rise to the musical piece, which then can interact with all the other cinematographic elements. As in Gabbeh (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996), this is a scene in which everything sings, woven into the type of musique concrète soundscape so characteristic of Akerman.

To grasp the shock that the move prepared by Akerman for shot 3 will cause us, it is crucial to look back over the work with repetition and variation that typifies her cinema (and specifically this film). Throughout Nuit et jour, we have already witnessed, four times over, a scene similar to the one we are analysing: Jack and Julie leaving their home. Sometimes, Akerman begins by showing us the pair descending the stairs; at other times, she opens the scene with the exterior shot of the building’s façade. Only on one occasion do we see the characters walking off together, in an embrace; usually, the two head off in opposite directions – Julie to the left and Jack to the right of frame. However, in this fragment, Akerman introduces something totally unpredictable – the least expected move in the scene: a mid-shot of Joseph, Julie’s nighttime lover, who is watching the couple from the other side of the street.

Shot 3

Sitting on a bench, with his chin resting on his folded arms, Joseph looks at Julie with a mix of sadness and helplessness. Even though he is well aware that Julie is in another relationship, this is the first time, since the beginning of their affair, that he has seen her in Jack’s presence. The shot is held for almost four seconds, in which we can notice how the muscles in Joseph’s face relax slightly, how he releases his tight lips while breathing and gulping saliva. To understand the magnitude of what we are witnessing in these small gestures, it is necessary to know that, the night before, Julie missed – for the first time – her appointment with Joseph. And so, in this shot, the character of Joseph passes from the nervousness, excitement and uncertainty of waiting, to a sudden devastation provoked by the gravity of this unforeseen vision.

The action is completely arrested, frozen for a few seconds, in stillness and silence. We go to a close-up of Julie (shot 4) that constitutes the most intense and weightiest move of the scene. It is an atypical shot for Akerman, more reminiscent of Scorsese: the camera frames Julie – with her characteristic, enigmatic, Mona Lisa expression – and then pushes in slightly closer to her, from below: a true underlining from Akerman’s caméra-stylo, a stylistic gesture that marks her own identification with (and desire for) her female protagonist. Still frozen, Julie blinks – what a stupendously dramatic, perfectly timed blink – and then she smiles slightly, turns sharply, and clack-clacks away. It feels like a decisive gesture – but we hardly ever know what Julie has decided, why or when, in this story, even in its remarkable, final sequence-shot.

Shot 4

Something very strange and unusual happens in this scene: after shot 2, Jack disappears – both literally and figurally. We assume that he is off-frame, next to Julie, until she turns and leaves, and that he then departs on his own, usual course. However, there is absolutely nothing – neither image nor sound – that allows us to accurately determine when (or even if) this happens: it is as if Joseph’s gaze has blocked out Jack, and that therefore this is enough to erase him altogether from the frame and from the scene. While it is the case that Akerman rarely employs conventional shot/reverse shot, here she enjoys evoking something resembling its simulacrum. The consecutive angles on Joseph (shot 3) and Julie (shot 4) share a similar scale and tonal luminosity (the dusk light prodigiously used in the film); as well, the view of Julie is taken from an angle that corresponds with Joseph’s seated position. Akerman creates such a perfect, imaginary continuity between these shots that, for a moment, everything else around them fades away. Julie and Joseph are alone, isolated, in what appears to be a moment of shared intimacy. And we – despite well knowing that these characters are not literally that close to each other – are fully immersed in this sweet mirage.

Shots 3 and 4: creating a moment of shared intimacy

The special intensity of this fragment derives from the combination of the micro-movements that compose it, and the residue of ambiguity it leaves in us. In Nuit et jour Akerman forces us, constantly, to turn back and process what we have just seen; quite frequently, the perception we first had of a shot is modified or placed in doubt by the following shot. This is precisely what happens here, and it is what gives this moment its enigmatic, brooding aura. As always, the emotion of the scene is in the layering, the mixing, the adding and subtracting. This process of thinning and thickening the scene has a direct, visceral effect of making the fictional world seem dull and heavy, or light and free; even more profoundly, the passage from one arrangement of formal elements to another dissolves the world, or recreates it, or returns us to it with a thud.

Here, the music is one of the main elements that effects such dynamic transitions. The piece by Villa-Lobos rises as a low, storm-cloud-gathering rumble under the face-off between Julie and Jack. It gains intensity and volume as the sound of Julie’s shoes disappears, fading out in the off-screen distance. The main melodic line for the cello imposes itself in the next shot (number 5) as Joseph stands up and begins his laterally-tracked walk, his eyes fixed on Julie off-screen, before he exits at the right-hand edge of the frame. This shot also works as a return to reality: rediscovering Joseph’s position as voyeur, and re-marking the distance between him and Julie. (In fact, when Joseph gets up to walk, keeping his eye on Julie all the way, she must already be far off down the street: Akerman, like Godard, is unafraid of such spatial unrealism.) It is through this move that we understand what we have witnessed only an instant ago: the shot of Julie is revealed to be a magnification of that moment in which Joseph sees her, for the first time, offering a smile to another man. Here we have a subjective shot in the most profound and intimate sense of the term: the camera does not take the place of Joseph’s eyes, but his heart.

Shot 5

In this short scene, Akerman has transformed a tiny, simple gesture – Julie and Jack turning to look at each other, a third party nearby – into an incredible and mysterious moment of intrigue, sustained over five separate shots. Then, in a truly beautiful cut, Akerman takes us to the vision of Julie sitting in a cafe, tracking the approach of Joseph, like a camera, with the steady, steely movement of her eyes. This moment is itself a repetition/variation on something we have seen before: earlier, it was him in this same spot, awaiting her. She is merely sitting in a cafe, but it is as if she, and we, are in heaven: music has now replaced all ambient sound and, pictorially, the line of reflected out-of-focus car lights in the window redraws and redefines the spatial reality – a striking example of the plasticity of Akerman’s style. And it is as if all of this taken together – the music, the lights, the gravity-free zone, her eyes – are drawing this guy so sweetly into the frame, into their shared two-shot.

Shot 6

This heaven, however, does not and cannot last: the soft toot of a car horn cues the return of ambient sound, and ushers in the somewhat jealous and tormented dialogue that ensues between this couple. But before that talk begins, the film has burned into our mind’s eye the special memory of Julie’s smile as she sits in this cafe and looks beyond its window: a smile that is always the same and yet always new, because it expects nothing, anticipates nothing, except the present moment of absolute joy in which it participates.

© Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin, October 2015

(*) This text first appeared, in French translation, in Chantal Akerman, eds. Dominique Bax and Cyril Béghin (Bobigny: Magic Cinéma, 2014).