Apuntes para una teoría del cine

Secreto e imposible

Click here for the English version

“El objeto sensual persiste (memoria), despliega un estilo único (elocutio), organiza sus notas y sus partes (dispositio y ordo), y contiene un núcleo fundido que se aparta de todo contacto (inventio)»

Tim Morton, “Sublime Objects” (2011)

Todo buen filme tiende a tener dos cosas: algo secreto y algo imposible. Muchas películas tienen solo una de esas cosas (y la mayoría de ellas, ninguna). Los mejores filmes tienen las dos cosas.

En el arte, la idea del secreto no es nada nuevo. En cierto modo, es una concepción habitual de todo análisis –también del psicoanálisis clásico-, de todos los estudios hermenéuticos, heurísticos. La película guarda un secreto que es precisamente aquello que no se dice, aquello que no se declara. Muy preferible a todos esos filmes (muchos filmes-ensayo, por ejemplo) que nos dicen exactamente de qué tratan y, de paso, qué vamos a pensar y a escribir sobre ellos. El secreto –el núcleo secreto del filme- es algo bastante distinto. Es el agujero, el gran vacío en medio de la película, el gran “no dicho” que genera todo lo que realmente se dice, se muestra, se ve, se oye, se imagina. Jean-Pierre Gorin lo expresó bien (y nosotros lo parafraseamos de memoria): en el centro de mi filme hay algo que no puedo decir, que no puedo articular, a lo que no puedo enfrentarme, que no puedo admitir. Si pudiera decirlo, quizás no haría la película.

De algún modo todo el filme sugerirá, se aproximará y aludirá a este núcleo secreto. Nosotros debemos descifrarlo. En una de las primeras secuencias de Inland Empire (2006), David Lynch introduce a un personaje femenino que llora frente a la pantalla de un televisor. Ella no habla, ni siquiera tiene nombre. Es solo una presencia sometida a los mecanismos de proyección e identificación. Un cuerpo desnudo, un rostro surcado por las lágrimas, unos ojos que absorben y exteriorizan emociones. Pero, ¿qué es lo que esta mujer ve en esas imágenes? ¿Qué es lo que recibe de ellas? Eso nunca lo sabremos. El núcleo secreto guía al filme. Lo sentimos, pero no podemos tocarlo. Es el fantasma que lo explica todo, el cómo y el por qué se manifiesta en la superficie del texto, dándole profundidad, volumen, resonancia. Y misterio.

El núcleo secreto no tiene que ser un secreto gótico (aunque a veces lo es). Tampoco tiene que ser un trauma, un algo sucio o una cicatriz interior. En ocasiones, el núcleo secreto de la película es algo operativo, algo que funciona también como generador del filme y después se mantiene enterrado. Viendo Eyes Wide Shut (1999) de Stanley Kubrick nos asaltó el pensamiento de que toda la película es una especie de ilustración desplazada de una canción que no aparece en ella: “The Guests” de Leonard Cohen. El drama de la fiesta, de la desaparición, del viaje, del abandono, «muchos los de corazón roto, pocos los generosos de corazón”. David Lynch admitió una vez que Carretera perdida (Lost Highway, 1997) surgió de su meditación o ensoñación (hay que admitirlo: surrealista) sobre los detalles del caso de asesinato perpetrado por O.J. Simpson que se emitían diariamente en los informativos nocturnos. Raúl Ruiz nos da indicios de que muchos de sus guiones están basados en textos, o incluso en pequeños fragmentos de textos, de los que no compró los derechos de autor, sin embargo es ahí donde se encuentra la génesis de las películas.

Lo imposible es otro tipo de límite, otro tipo de vacío en un filme. Marca una frontera, un reino al que no se puede acceder. Se trata de algo que no puede representarse, que no puede ser figurado. En el filme de José Luis Guerin En la ciudad de Sylvia (2007) un hombre viaja a Estrasburgo, ciudad donde, años atrás, conoció a una mujer llamada Sylvie. Una tarde cree reconocer a esa mujer en la terraza de un café. La visión se produce a través de la ventana del bar, como si se tratase de una proyección pura del deseo del protagonista. Guerin filma esto en una secuencia magistral: el cristal actúa como pantalla sobre la que se impresionan un conglomerado de formas, un amasijo de cuerpos y rostros femeninos. De entre todos ellos emerge la imagen difusa de Pilar López de Ayala, la actriz que interpreta a la protagonista femenina. Pero en la escena siguiente se revela el equívoco y la fantasía es bruscamente interrumpida: ella no es la Sylvie a la que él andaba buscando. En el filme de Guerin todo gira alrededor de esa imagen imposible, de esa imagen que conforme a cierta lógica de lo sagrado no puede ser mostrada porque hacerlo, representar lo irrepresentable, equivaldría a una herejía.

En su libro de relatos Quel bowling sul Tevere, Michelangelo Antonioni escribe lo siguiente: “Detrás de cada imagen revelada hay otra imagen más cercana a la realidad. Y en el fondo de esta imagen hay otra imagen aún más fiel, y otra detrás de esta última, y así sucesivamente… Hasta la verdadera imagen de la realidad absoluta y misteriosa que nadie verá nunca”. Guerin jamás nos mostrará a la mujer que da título a su filme. En Inland Empire nunca llegaremos a conocer los contornos reales de la experiencia que la muchacha proyecta sobre las imágenes que está viendo. Ambas películas velan por esa imagen de una “realidad absoluta y misteriosa”, evocada por Antonioni. Todo lo que nos queda son filmes dentro del filme, sobreimpresiones y palimpsestos, rostros que esconden y esbozan ese rostro que, sin embargo, no veremos nunca.

Cuando falleció el filósofo Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, en enero de 2007, una cita apareció en un homenaje que le dedicaron: para él, escribir fue siempre una cuestión relacionada con lo imposible. Aquello que es imposible decir o representar. Todo arte, toda escritura, toda película, gira en torno a ese imposible: es un intento de delinearlo, de acercarse a él de algún modo. Y, al final del proceso, esa es la única dignidad poética: el haber expresado algo a partir, precisamente, de la admisión de esa imposibilidad.

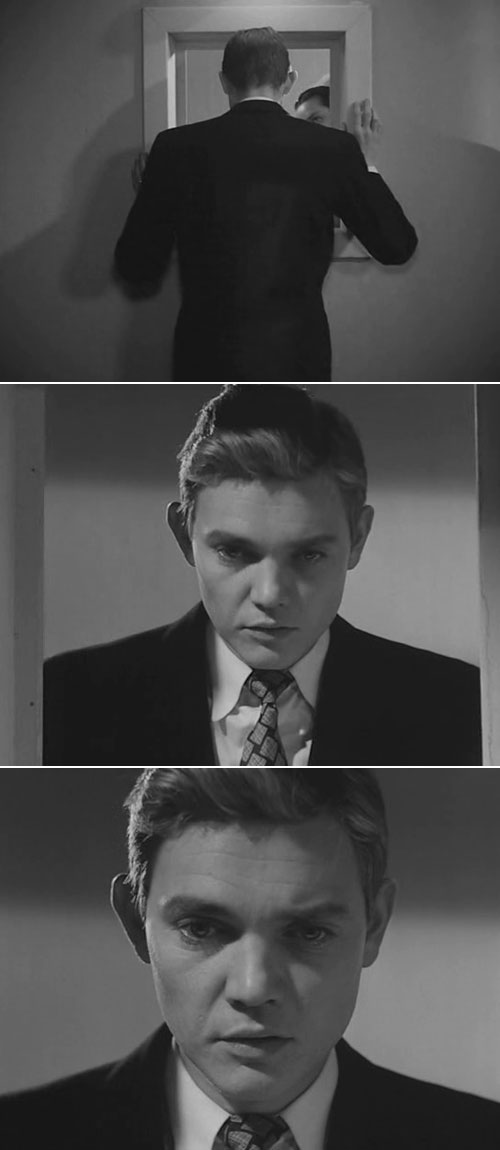

Recordamos una película del gran Ingmar Bergman, que también murió en 2007. Un verano con Mónica (Sommaren med Monika, 1952), un filme que estaba embrujado y marcó a muchísimos directores y críticos. Durante gran parte de la película, el joven héroe adulto es un personaje vacío: solo los ojos que observan a Monika, una presencia informe a la que ella debe incitar, empujar y moldear para que se convierta en su objeto de deseo pasajero. Esto es así hasta que Monika queda embarazada y da a luz. De repente ese hombre de ningún lugar se convierte en el núcleo central del filme. De repente, sus ojos pertenecen a un cuerpo, a un alma, a una pasión resentida –muy central para este director a quien tanto le gustaba abordar pasiones resentidas. Ahora el personaje puede ser un álter ego apropiado para el autor. El hombre va a ver al pequeño (por supuesto, solo después de que Monika se lo pida) y lo único que siente es una envidia instantánea, incluso criminal, por ese niño que viene a poner fin a la pasión sexual de su matrimonio, interponiéndose entre el hombre y la mujer, entre el marido y la esposa. Él mira al pequeño con ese odio abrasador, ¡pero nosotros no vemos al bebé en la cuna! El contraplano es imposible. Tan imposible como cuando, en una escena posterior, él ve a Mónica en la cama con otro hombre que le golpeó y le ridiculizó. Lo que crea la zona de imposibilidad aquí es la humillación. Eso es lo que le da a la película su lado duro, afilado: más allá de esto solo podemos imaginar.

Nosotros debemos buscar el secreto, debemos intuirlo. Y también debemos imaginar lo imposible. Estas dos zonas son las que dan al gran cine su forma y su emoción.

Secret and Impossible

Click aquí para la versión en español

“The sensual object persists (memoria), it displays a unique ‘style’ (elocutio), it organises its notes and parts (dispositio and ordo), and it contains a molten core that withdraws from all contact (inventio)”.

– Tim Morton, “Sublime Objects” (2011)

Any good film tends towards having two things: something secret and something impossible. Many films only have one of these things (and very many others have neither thing). The best films have both things.

The idea of the secret in art is not new. In a way, it is a standard idea of all analysis – classical psychoanalysis, too. All hermeneutic, heuristic analysis. The film holds a secret that is precisely the thing it does not say, does not declare. Far preferable to all those films – so many essay-films, for instance – that tell us exactly what they are about and what we are to think and write about them in turn. The secret – the secret centre – is something quite different. It is the hole, the great blank at the middle of a film, the great unsaid, that generates everything that is actually said, shown, seen, heard, imagined. Jean-Pierre Gorin once said it well (and we paraphrase it from memory): at the centre of my film is something I cannot say, cannot articulate, cannot face, cannot admit. If I could say it, maybe I would not make the film.

The whole film will somehow approach, somehow intimate, somehow allude to this secret centre. We must decipher it. In an early sequence of Inland Empire (2006), David Lynch introduces a female character who appears crying in front of a television screen. She doesn’t speak, doesn’t even have a name. She is merely a presence subjected to the mechanisms of projection and identification. A naked body, a face streaked by tears, two eyes that absorb and externalise emotions. But what is it that the woman sees in these images? What does she get from them? We will never know. The secret centre drives the film. We feel it, even as we cannot put our finger on it. It is the phantasm that explains everything, the how and why it manifests itself on the surface of the text. It gives depth, volume, resonance. And mystery.

The secret centre does not have to be a Gothic secret (although sometimes it is). Doesn’t have to be a trauma, something dirty, an inner scar. Sometimes the secret centre is something operative, a generative tool that is then kept buried. Watching Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), we became inflamed by the thought that the whole film was a kind of displaced illustration of a song that does not appear in it: Leonard Cohen’s “The Guests”. The drama of the party, of the banishment, of the journey, the abandonment, “the broken hearted many, the open hearted few”. David Lynch once admitted that Lost Highway (1997) arose from his (admittedly surreal) meditation or reverie upon the nightly-news details of the O.J. Simpson murder case. Raúl Ruiz hints that many of his scripts are based on a text, or even a tiny fragment of a text, for which he did not buy the rights, but nonetheless generates everything from …

The impossible is another kind of limit, another kind of blank in a film. It marks some point, some realm into which it cannot enter. Something it cannot depict, or figure. In José Luis Guerin’s In Sylvia’s City (2007), a man travels to Strasbourg, the city where, years before, he knew a woman named Sylvia. One afternoon, he thinks he recognises this woman on the terrace of a café. The vision takes place through the bar window, as if it were a pure projection of the protagonist’s desire. Guerin films this in a magisterial sequence: the glass functions as a screen upon which a conglomeration of forms is impressed, a jumble of female bodies and faces. Out of them all emerges the vague image of Pilar López de Ayala, the actress who plays the central woman. But, in the following scene, the ambiguity is cleared up and the fantasy is abruptly terminated: this is not the Sylvia whom he has walked around looking for. In Guerin’s film everything turns around this impossible image, this image that – conforming to a certain logic of the sacred – cannot be shown because to do so, to represent the unrepresentable, would be equivalent to heresy.

In his book of tales That Bowling Alley on the Tiber (Oxford University Press, 1986), Michelangelo Antonioni writes the following: “We know that underneath the revealed image there is another that is more faithful to reality, and beneath this still another, and again another until this last. And on up to that true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that nobody will ever see” (‘Translator’s Preface’, p. ix). Guerin will never show us this woman whom his film is named after. In Inland Empire we will never get to know the real contours of the experience that the girl projects onto the images she is seeing. Both films stand watch over that image of an “absolute, mysterious reality” evoked by Antonioni. All we have left is films within the film, superimpositions and palimpsests, faces that hide and outline this face that, nonetheless, we will never see.

When the philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe died in January 2007, a quotation surfaced in a tribute: writing, for him, was always about the impossible. The thing it is impossible to say or represent. All art, all writing, all film, is this attempt to somehow delineate, somehow cruise around this impossible. And that, at the end of this process, that is the only poetic dignity: to have expressed something precisely via this admission of impossibility.

We remember a film by the great Ingmar Bergman, also dead in 2007. Summer with Monika (1952), a film that was haunted and influenced so many directors and critics. For much of this film, the young adult hero is a blank: just the eyes that see Monika, the blobby presence she must prod and push and mold into her passing object of desire. That is, until she becomes pregnant and gives birth. Suddenly this nowhere-man becomes the burning centre of the film. Suddenly his eyes belong to a body, a soul, a spiteful passion – very central to this filmmaker who so loved to present spiteful passions. Now he can be a fitting alter ego for the auteur. The man goes to look at his little baby child (after Monika tells him to, of course). He feels nothing but instant, even murderous envy for this baby who comes to end the sexual passion of his marriage, to get between man and woman, husband and wife. He gazes at the child with this burning hatred. But we do not see the child in its hospital crib! The counter-shot is impossible. Impossible here, just as it is some scenes later, when he sees Monika in bed with another man, a man who beat and ridiculed him. The humiliation creates the zone of impossibility. It gives the film a hard, sharp edge: beyond here, we must only imagine.

We must look for, must intuit the secret, just as we must imagine the impossible. Both zones give great cinema its form, and its emotion.

Textos y traducciones © Adrian Martin y Cristina Álvarez López, agosto 2007/diciembre 2011. Texts and translations © Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López, August 2007/December 2011