Girls

Sobre la ternura

Click here for the English version

“No conozco nada que despierte en mí una emoción tan profunda”, escribió Jean Epstein en 1928, “como un rostro que, a cámara lenta, da a luz una expresión. Primero, toda una preparación, una fiebre lenta que uno no sabe si comparar a una incubación mórbida, a una maduración gradual o, más toscamente, a un embarazo. Finalmente, todo este esfuerzo se desborda, rompe la rigidez de un músculo. Un contagio del movimiento anima al rostro, el ala de las pestañas y la borla del mentón también empiezan a temblar. Y, cuando los labios por fin se separan para anunciar el grito, nosotros hemos asistido a todo su largo y magnífico albor” (1)↓.

Dos rostros. Una madre y una hija, algunos rasgos de la más mayor se proyectan sobre la más joven. Estamos al final de Tiny Furniture (Lena Dunham, 2010), cuando Aura -interpretada por la propia Dunham-, exhausta tras un perturbador encuentro sexual, se mete en la cama con su madre (Laurie Simmons). Aura confiesa haber leído los diarios que la otra escribía cuando era adolescente. «No me importa,» afirma la madre. «¿Quién era Ed? ¿Quién era Phil?», pregunta Aura. “Si nada de lo otro funciona”, dice la madre, «siempre puedes dedicarte a los masajes terapéuticos. Eres muy intuitiva».

Durante este intercambio, que se prolonga varios minutos, la cámara permanece cerca de ellas, flotando justo por encima del cubrecama, inclinándose en el corte entre los dos rostros. La escena no está filmada a cámara lenta, pero el encuadre fijo y la lentitud de la conversación hacen que nuestra atención se centre en las expresiones. Cada ligero movimiento del rostro queda registrado, construyendo un catálogo de breves espasmos musculares y de gestos que cambian a cada minuto. Vemos las raíces grises que asoman bajo el pelo rojo de Laurie Simmons; vemos su mirada que se desplaza velozmente de un lado a otro y el borde de sus fosas nasales que se hincha ligeramente cuando respira. Hay poca profundidad de campo y los planos están encuadrados de tal manera que la parte superior de las cabezas de ambas sale fuera de este; la energía de las actrices queda atrapada, concentrada, dentro del cuadro, y nuestra mirada es arrastrada hacia sus rostros. Es un momento de pura ternura en una película que, en su mayor parte, ha transcurrido entre bromas incómodas e ingeniosos diálogos a la defensiva. A partir de esta presentación extendida del rostro somos invitados a entrar en su intimidad. Es un gesto potente.

Esta imagen se repite, volteada, al comienzo de Girls, la nueva serie para televisión de Dunham, estrenada en la HBO en abril de 2012. Esta vez, Dunham es Hannah Horvarth, y no es con su madre con quien está acostada, sino con su amiga y compañera de piso Marnie (Allison Williams). La cámara se desliza a lo largo de dos pares de piernas entrelazadas y se detiene en los rostros de las dos chicas. Ambas duermen, vestidas con pijamas infantiles. Marnie lleva retenedores en los dientes. Poco después, veremos la primera imagen de Jessa (Jemima Kirke), también dormida en la parte trasera de un taxi, su cabeza reposando sobre una pila de maletas Vuitton.

A través de estos primeros planos, emerge una imagen de la ternura que distingue a Girls del grueso de la comedia televisiva. Mientras otras series trabajan creando emoción en forma de pathos -pensemos, por ejemplo, en el Gerry de Parks and Recreation-, Girls busca a tientas los éxtasis cinematográficos de Epstein a partir de prolongados primeros planos y de la presentación franca del cuerpo en movimiento. Aquí los rostros mutan, amenazando siempre con echarse a reír o a llorar; vacilan ansiosamente, están al borde de transformarse, bocas temblorosas, cejas inseguras. Los personajes hablan, y hablan, y hablan, como si el lenguaje pudiera, de algún modo, liberarlos de la incómoda sensación de ser un cuerpo.

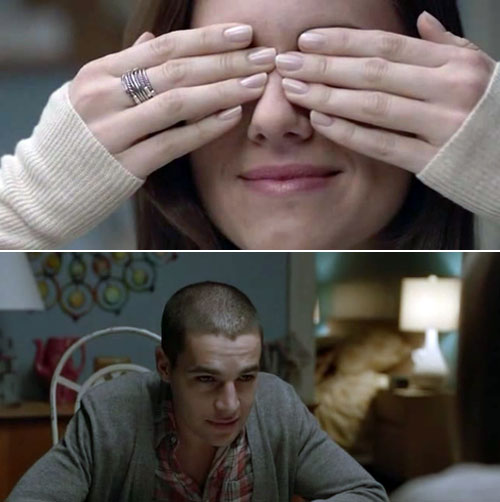

El tercer episodio, titulado “All Adventurous Women Do”, comienza con un primer plano de Marnie. Ella sonríe, sus dedos presionando sus ojos. “Ábrelos”, dice Charlie desde fuera del plano, y Marnie abre los ojos lenta y cautelosamente. La cámara permanece fija en su cara hasta que su sonrisa se desvanece. Apenas necesitamos ver el contraplano de Charlie con su cabeza rapada. La dinámica de su relación queda expresada con claridad en ese sencillo desplazamiento que va de la anticipación a la consternación. Un momento después, Marnie pondrá en palabras la cuestión central de Girls: el vínculo entre la identidad y el cuerpo. «Tócala», dice Charlie inclinando su cabeza afeitada hacia Marnie. «No», responde ella, «siento como si ya no te conociera».

Al principio de la serie, Hannah comunica a sus padres: «Estoy ocupada, tratando de convertirme en quien soy.» Durante el resto de la temporada, este “convertirme” irá enraizándose firmemente en el cuerpo. Durante los siguientes diez episodios, el vientre de Hannah será sacudido por Adam (Adam Driver), sus cejas serán perfiladas exageradamente por una compañera de trabajo, y los pijamas con los que la veremos pasearse están tan desgastados y sin forma que casi podemos oler el sudor en ellos. Como a Marnie, a Hannah le cuesta negociar los términos de ese resbaladizo contrato entre las cosas y su apariencia. Cuando decide comunicarle a Adam que quiere algo más que sexo, cuando le dice -sin decirlo realmente- que le gusta, su rostro refleja la lucha entre sus sentimientos y su deseo por no perder la compostura. De pie, en el umbral de la puerta de casa Adam, encuadrada desde el punto de vista de él, la cámara hace un zoom muy lento sobre su rostro de modo que, cuando termina de hablar, vemos su prominente mentón tembloroso contra el borde inferior del cuadro. Sus histriónicas cejas pintadas se elevan hasta el borde superior -una inyección de comicidad en un momento que, por lo demás, es bastante serio-.

Cada vez que Hannah intenta hablar con dureza, su cuerpo la traiciona. En el quinto episodio, “Hard Being Easy”, Adam toma las palabras de Hannah al pie de la letra y rechaza su oferta sexual. En un intento de provocarle, ella le cuenta que ha estado a punto de acostarse con su jefe «solo por joder». Pero un momento más tarde la vemos en el lavabo, desplomada, su rostro tembloroso intenta no sucumbir a las lágrimas. Después encuentra a Adam haciéndose una paja en su habitación. “¿Te pone cachonda ver cómo me toco la polla? ¿O te da asco?”, le pregunta él. En Girls, esta porosa frontera entre la excitación y la repugnancia es representada una y otra vez. En esta ocasión, Hannah comienza a seguirle el juego. Mientras le mira desde el umbral de la puerta, asiente: «Es patético y feo y asqueroso y raro y perezoso». Hannah levanta su falda pero él la detiene; la confusión entre lo que ella siente por Adam y lo que piensa que él siente por ella la abruma. «Quiero dinero para el taxi», dice Hannah. Pero Adam incorpora esa petición al juego mientras Hannah coge dinero del cajón. Cuando finalmente se corre, deja ir un sonoro grito de alegría. «Chócala», dice Adam extendiendo su mano. Para él, el cuerpo es una fuente de placer constante.

Dunham ha sido a la vez elogiada y menospreciada por mostrar su cuerpo en todo su descuidado esplendor. Su presencia, decididamente prosaica, es una parte central de su interpretación. Esta interpretación, sin embargo, no parece tan interesada en hacer pedazos los estereotipos de representación como en mostrar la torpeza de su personaje para estar a la altura del marco adulto de su propio cuerpo. Girls es una serie tremendamente física. La desnudez irreprimible de Adam, la interminable melena de Jessa, y la manera en que Hannah se arrastra con los hombros caídos, hacen que el elenco pase de ser un simple conjunto de personajes a ser una constelación de cuerpos trepidantes. Hay, en algunas acciones, rastros del cine físico de Charlie Chaplin y de Buster Keaton. Mientras es empujada a través de la noche después de una fiesta, Hannah cae de la parte delantera de la bicicleta de Adam como si fuese una muñeca de trapo -esto es un eco de su colapso en el primer episodio, cuando arruga el rostro frente a sus padres en un desesperado despliegue de pánico infantil-. Este mismo capítulo cuenta también con una persecución al estilo de Mack Sennet: en pleno subidón de crack y sin pantalones, Shoshanna (Zosia Mamet) huye de Ray (Alex Karpovsky) como si fuese una muñeca mecánica.

La fascinación del cine primitivo con un cuerpo irrompible también deja su marca en la experiencia del sexo como algo caótico, descoordinado. Adam sacudiendo la barriga flácida de Hannah mientras conjura un universo de excéntricas fantasías, Jessa y un ex-novio abalanzándose contra la ventana mientras Shoshanna -presa de la repulsión y de la fascinación- los observa, Marnie queriendo seducir a Charlie pero dejándose puesto el sujetador mientras tienen relaciones: en Girls la unión de los miembros es siempre tan triunfal como incierta. Los personajes son elásticos, flexibles; después de cada tropiezo, se recuperan; puede que estén cubiertos de polvo, pero no se dan por vencidos.

Al final de la temporada, nos quedamos con Hannah esperando un tren. La cámara se sitúa al lado de su rostro. El balanceo suave de su mano es la encarnación visual del movimiento oscilante de su cuerpo. Mientras el tren se acerca al andén, el pelo de Hannah revolotea como si estuviese filmado a cámara lenta. Y luego, con esa misma parsimonia, ella se desplaza hasta el tren; apoya su cabeza contra la ventana, cierra los ojos y duerme hasta el final de la línea.

Los últimos planos están dedicados al cuerpo de Hannah. Sus pies descalzos caminando por la arena; su espalda y la parte superior de su cabeza filmadas desde arriba. Su sombra, como una gemela gigante que cruza la playa en diagonal. En la última imagen la vemos comiendo un pastel. Hannah lame sus dedos. Es un gesto de despedida del deseo carnal, mostrado de manera sencilla, con inmensa ternura.

Traducción: Cristina Álvarez López

(1)↑ Jean Epstein, “Bonjour Cinema and other writings”, Afterimage, Otoño, 1981, p.24. (La traducción es mía).

On Tenderness

Click aquí para la versión en español

“I know of nothing more utterly moving,” wrote Jean Epstein in 1928, “than a face giving birth to an expression in slow motion. A whole preparation comes first, a slow fever, which it is difficult to know whether to compare to the incubation of a disease, a gradual ripening, or more coarsely, a pregnancy. Finally all this effort boils over, shattering the rigidity of muscle. A contagion of movement animates the face. The eyelash wing, the jaw a spur, begin to stir too. And when the lips finally part to herald the cry, we have attended the whole of its long and magnificent dawning” (1)↓.

Two faces. A mother and daughter, a faint trace of the older woman’s face hovering over the younger’s. We are at the end of Tiny Furniture (Lena Dunham, 2010) when Aura (Lena Dunham), exhausted after an unsettling sexual encounter, climbs into bed with her mother (Laurie Simmons). Aura confesses she’s been reading her mother’s teenage diaries. “I don’t care,” her mother says. “Who was Ed?” Aura asks, “Who was Phil?” “If film making doesn’t work out,” Aura’s mother tells her, “You could always become a massage therapist. You’re got very intuitive hands.”

Throughout the exchange, which runs for several minutes, the camera stays close, floating just above the coverlet, tilting on the cut between the two faces. The scene is not in slow-motion, but the stillness of the frame and the slowness of the conversation focus our attention on the expressions. Every slight movement of the face is registered, making up a catalogue of minute shifts and tiny muscular spasms. We see the grey roots under Laurie Simmons’ red hair, the way her gaze darts back and forth, and the way the edge of her nostril flares slightly as she breathes. The depth of field is low and the shots are framed so that the top of both heads are cut off, trapping the actors’ energy in the frame and drawing our gaze into the face. It is a moment of pure tenderness in a film that has mostly filled out its running time with wittily defensive dialogue and awkward jokes. Through the extended presentation of the face we are invited in. It is a powerful gesture.

This image is flipped and repeated at the beginning of Dunham’s recent television series, Girls, which premiered on HBO in April 2012. This time, Dunham is Hannah Horvarth, and it’s not her mother she’s spooning, but her friend and housemate Marnie (Allison Williams). The camera glides along two pairs of entwined legs and comes to rest on the two girls’ faces. They are asleep, dressed in childish pajamas. Marnie has her teeth in a retainer. A few moments later, we are given our first glimpse of Jessa (Jemima Kirke), also asleep in the back of a taxi, her head resting on a pile of Vuitton suitcases.

Through these close-ups, an image of tenderness emerges that distinguishes Girls from the main body of television comedy. While other shows provide heart in the form of pathos – just think of Gerry in Parks and Recreation – Girls fumbles toward Epstein’s cinematic ecstasies through extended close-ups and the frank presentation of the body in motion. Faces here are mutable, forever threatening to collapse into tears or laughter. They teeter anxiously in a state of becoming, eyebrows unsure, mouths wavering. The characters talk, and talk, and talk, as if language might somehow free them from the uncomfortable sensation of embodiment.

The third episode, titled ‘All Adventurous Women Do’, begins with a close-up of Marnie. She is smiling, her fingers pressed over her eyes. “Open them,” Charlie says off-screen, and her eyes stretch open. The camera stays fixed on her face as her smile fades. We hardly need to see the reverse shot of Charlie with his head shaved. The dynamic of their relationship is neatly expressed with that simple shift from anticipation to dismay. A moment later Marnie voices the question central to Girls, that of the link between identity and the body. “Touch it,” Charlie says, leaning his shorn head toward her. “No,” Marnie replies, “I feel like I don’t know you anymore.”

At the very beginning of the show Hannah tells her parents, “I’m busy, trying to become who I am.” For the rest of the season, this becoming will be rooted in the body. Over the next ten episodes, Hannah will have her belly shaken by Adam (Adam Driver), receive some extreme eyebrows from a workmate, and wander around in pajamas so worn and shapeless you can almost smell the sweat on them. Like Marnie, Hannah struggles to negotiate the slippery bond between things and their appearance. When she decides to tell Adam that she wants more than sex, that – without actually saying it – she likes him, the struggle between her feelings and her desire to maintain her cool are played out on her face. As she stands in Adam’s doorway, framed from his point of view, the camera very slowly zooms in, so that by the time she’s done speaking she is framed with her quivering chin jutting against the bottom of the frame. Her dramatically painted eyebrows rise to the upper edge, a jolt of a joke in an otherwise serious moment.

Whenever she tries to talk tough, Hannah’s body betrays her. In the fifth episode, ‘Hard Being Easy’, Adam takes her at her word and turns down her offer of sex. In an attempt to provoke him, she tells him she almost slept with her boss “to just be an asshole.” But a moment later we see her slumped on the toilet, face quivering as she tries not to cry. Afterward, she finds Adam jerking off in his room. “Does it turn you on,” he asks, “to watch me touch my own cock? Or does it disgust you?” This porous border between arousal and disgust is played out over and over in Girls. In this instance Hannah begins playing along. Standing in the doorway watching Adam, she agrees. “It’s pathetic and bad and disgusting and weird and lazy,” she tells him. She lifts up her skirt but he stops her, and the confusion of what she feels for Adam and what she thinks he feels for her overwhelms her. She stops playing the game. “I want cab money,” she says. But then, when he incorporates her request into the game, keeps playing as she takes money from his drawer. When he finally comes, he lets out a huge whooping laugh. “Shake my hand,” he says. For Adam, the body is a source of continual delight.

Dunham has been both praised and belittled for displaying her body in all its unkempt glory. Her resolutely earthbound presence is a central part of her performance, but it seems to be less about smashing stereotypes of representation and more about depicting the awkwardness of trying to catch up with one’s fully grown frame. Girls is a tremendously physical show. Adam’s irrepressible nakedness, Jessa’s endless mane of hair and Hannah’s slump shouldered shuffle transform the cast from a set of characters into a constellation of hurtling bodies. There is a trace of the physical cinema of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton in some of the action. Wheeling through the night after the warehouse party, Hannah is flung from the front of Adam’s bike like a rag doll, an echo of her collapse in the first episode, where she crumples before her parents in a desperate display of childish panic. This episode also features a Mack Sennet style chase, when Shoshanna (Zosia Mamet), high on crack and not wearing pants, runs away from Ray (Alex Karpovsky) like a mechanical doll.

Early cinema’s fascination with the unbreakable body also marks Girls’ chaotic, flailing sex. The joining up of limbs – Adam thrusting away over Hannah’s trembling belly while conjuring up a universe of kooky fantasies; Jessa and an ex-boyfriend plunging against the window while Shoshanna looks on, simultaneously repulsed and riveted; Marnie wanting to seduce Charlie but leaving her bra on while they have sex – is always as triumphant as it is unsure. They’re resilient, these characters, and after each stumble, they get back up, dusty but not done for.

At the end of the season, we are left with Hannah waiting for a train. The camera hovers beside her face. The gentle, hand-held rocking is the visual incarnation of the body’s wavering motion. As the train approaches the platform, Hannah’s hair blows back as if in slow-motion, and then she moves, at the same low speed, onto the train. She slumps her head against the window and closes her eyes. She sleeps to the end of the line.

The last few shots are devoted to Hannah’s body. Her bare feet walking across the sand; her back and the top of her head from above, with her shadow a magnified twin stretching across the beach. In the final image she is eating cake. She licks her fingers, a parting gesture of fleshy desire, shown simply, with immense tenderness.

(1)↑ Jean Epstein, ‘Bonjour Cinema and other writings’, in Afterimage (Autumn, 1981) p.24.

Texto original © Sarinah Masukor, julio 2012 / Traducción © Cristina Álvarez López, julio 2012