Los amantes del Pont-Neuf

Un drama de la piedra y el agua

Click here for the English version

“¿No sabes que en el agua puedes ver a la persona que amas?”

L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

Los amantes del Pont-Neuf (Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Leos Carax, 1991) es, en esencia, una historia de amor protagonizada por dos personajes que no pertenecen al mismo mundo. Como sucede con Pierre (Guillaume Depardieu) e Isabelle (Katerina Golubeva) en Pola X (Leos Carax, 1999) —filme que, en muchos aspectos, puede verse como una hábil variación (más oscura, más radical, más desesperada) de la película que nos ocupa—, aquí la relación entre Alex (Denis Lavant) y Michèle (Juliette Binoche) solo es posible cuando uno de los integrantes de la pareja —el que proviene de una familia acomodada, el que ha sido educado en el bienestar y la riqueza— decide abandonarlo todo para sumergirse en el universo del otro, para ingresar en esa comunidad de desheredados a la que no pertenece.

En Pola X este giro crucial en la vida de Pierre es retratado como una inmersión en la oscuridad de la noche comandada por la voz fantasmal y desgarradora de Isabelle. En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, en cambio, no llegamos a presenciar este desvío: cuando el filme arranca Michèle ya ha dejado atrás su pasado y vaga sola por las calles, con su cuaderno de dibujo bajo el brazo, sus ropas harapientas y su parche en el ojo.

En Mala sangre (Mauvais sang, Leos Carax, 1986), otro Alex —interpretado también por Denis Lavant— se retorcía ahogado por el cemento que no había podido digerir mientras estuvo en la cárcel y, al ritmo del Modern Love de David Bowie, emprendía una carrera desesperada para liberarse de ese peso. En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, el protagonista mantiene una lucha constante contra las superficies sólidas. En la secuencia de apertura, Alex, tendido sobre el pavimento de una calle, pone una mano en su nuca y empuja su cabeza de izquierda a derecha, frotando su frente contra el asfalto hasta hacerla sangrar. Más tarde, en mitad de un frenético baile junto a Michèle, estampa sus pies contra la roca mientras los fuegos artificiales explotan en el cielo y se derraman como gotas de rocío. A veces, este combate adopta la forma de un desafío sutil, como cuando el protagonista hace acrobacias sobre el puente o escala las paredes de los pasillos del metro. Pero este empeño de Alex por hacerse un cuerpo elástico y maleable es siempre un intento, quizás inconsciente, de trascender la solidez de las superficies, la impermeabilidad de la piedra y el hierro: es un grito de rebelión contra todo aquello que lo oprime.

En Mala sangre (Mauvais sang, Leos Carax, 1986), otro Alex —interpretado también por Denis Lavant— se retorcía ahogado por el cemento que no había podido digerir mientras estuvo en la cárcel y, al ritmo del Modern Love de David Bowie, emprendía una carrera desesperada para liberarse de ese peso. En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, el protagonista mantiene una lucha constante contra las superficies sólidas. En la secuencia de apertura, Alex, tendido sobre el pavimento de una calle, pone una mano en su nuca y empuja su cabeza de izquierda a derecha, frotando su frente contra el asfalto hasta hacerla sangrar. Más tarde, en mitad de un frenético baile junto a Michèle, estampa sus pies contra la roca mientras los fuegos artificiales explotan en el cielo y se derraman como gotas de rocío. A veces, este combate adopta la forma de un desafío sutil, como cuando el protagonista hace acrobacias sobre el puente o escala las paredes de los pasillos del metro. Pero este empeño de Alex por hacerse un cuerpo elástico y maleable es siempre un intento, quizás inconsciente, de trascender la solidez de las superficies, la impermeabilidad de la piedra y el hierro: es un grito de rebelión contra todo aquello que lo oprime.

Afirmar que el Pont-Neuf es el escenario que posibilita la historia de amor entre Alex y Michèle sería ceder a una tentación demasiado fácil. Si hay algo que el filme de Carax complica en extremo es ese carácter simbólico que otorga al puente el esatuto de pasaje, de vaso comunicante, de punto de encuentro entre dos personajes y dos mundos. Si aceptamos que este escenario es el que da cobijo al amor entre los protagonistas, debemos reconocer también que ese mismo lugar es el que constriñe su amor. Los amantes del Pont-Neuf evita, a toda costa, la romantización de la vida en la calle y, en especial, rechaza la falsa concepción que equipara la vida de los sin techo a una existencia libre de ataduras. En este filme, el puente es para Alex lo que para el burgués su casa. Viviendo en él se expone a las mismas fantasías y a los mismos peligros que cualquiera: poseer un lugar a cambio de ser poseído por este. Mientras la cárcel a la que Alex irá a parar al final del filme se convierte en el lugar que lo libera definitivamente, el Pont-Neuf es una prisión sin rejas que el protagonista teme abandonar porque solo cuando está recluido en ella se siente seguro.

Consecuentemente, Carax nunca filma el puente como paso o acceso, sino como límite. Y la película se inscribe por completo en este territorio fronterizo, incluso cuando abandona los confines del escenario que le da título. El director compone los planos del filme acentuando esa línea de piedra que atraviesa la imagen, que forma diagonales u horizontales que cruzan el encuadre y parten la pantalla en dos mitades irregulares. Un margen entre la tierra y el agua, entre el terreno mundano, conocido, habitado por los personajes y el universo mágico, acuático del mar o del río.

El amor entre Alex y Michèle nace y crece en esa región limítrofe pero, incuestionablemente, su horizonte es otro: los personajes pisan la piedra y, sin embargo, aspiran a otro ámbito, a uno capaz de amoldarse a sus cuerpos, capaz de aligerar y diluir el peso de sus lastres. Las superficies blandas, líquidas y permeables, que permiten y favorecen el tránsito: esos son los verdaderos pasajes de esta película. Para dar forma a este drama de la piedra y el agua Carax no solo trabaja la puesta en escena y la composición, sino que recurre a todos los elementos que están a su alcance. En este sentido, como veremos, es particularmente llamativo el trabajo de fotografía y de montaje a cargo, respectivamente, de Jean-Yves Escoffier y Nelly Quettier, colaboradores habituales del cineasta.

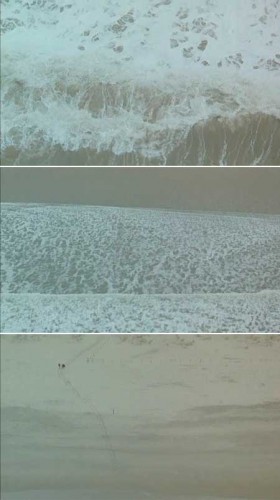

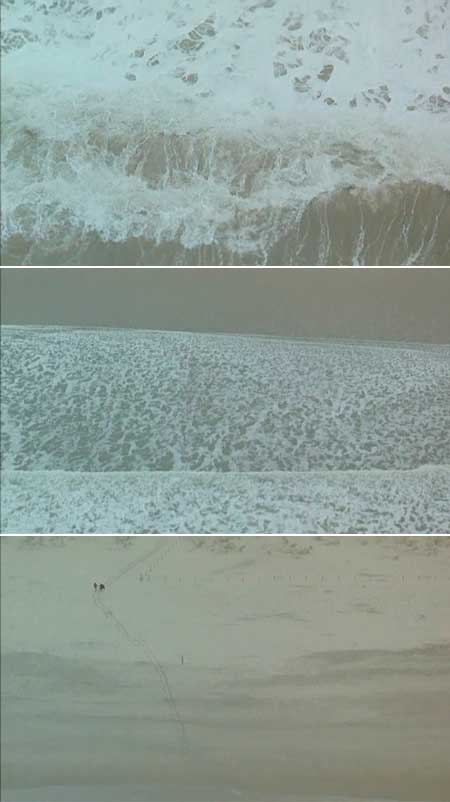

En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, el agua trae consigo un sentimiento de liberación que encontrará su máxima expresión en el desenlace del filme, pero que ya es prefigurado en dos de las secuencias más hermosas de la película. En una de ellas, Alex y Michèle escapan a la playa y corren desnudos por la orilla —otro límite que separa el mundo que habitan del destino hacia el que se inclinan—. Se trata de un momento extático, contagiado por una felicidad salvaje y nítida. A la mañana siguiente, un plano aéreo guiado por el movimiento pendular de la cámara nos conduce de las olas del mar al paisaje nevado. La imagen resultante es extraña, casi irreal; en ella, el blanco de la espuma y el de la nieve se confunden y apenas podemos distinguir donde termina un escenario y donde comienza el otro.

En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, el agua trae consigo un sentimiento de liberación que encontrará su máxima expresión en el desenlace del filme, pero que ya es prefigurado en dos de las secuencias más hermosas de la película. En una de ellas, Alex y Michèle escapan a la playa y corren desnudos por la orilla —otro límite que separa el mundo que habitan del destino hacia el que se inclinan—. Se trata de un momento extático, contagiado por una felicidad salvaje y nítida. A la mañana siguiente, un plano aéreo guiado por el movimiento pendular de la cámara nos conduce de las olas del mar al paisaje nevado. La imagen resultante es extraña, casi irreal; en ella, el blanco de la espuma y el de la nieve se confunden y apenas podemos distinguir donde termina un escenario y donde comienza el otro.

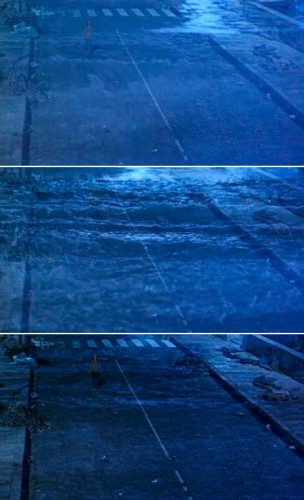

En otro fragmento del filme vemos a Alex conduciendo una lancha por el río mientras Michèle hace esquí acuático. La escena es un estallido de cascadas de agua y de luz, donde la velocidad del movimiento y las pulsaciones de la cámara producen una imagen llena de desenfoques abstractos y de colores parpadeantes. Cuando Michèle vuelca, Alex también se lanza al Sena. Durante unos segundos, vemos en la pantalla la sobreimpresión de dos imágenes: el alboroto del agua provocado por el chapuzón de Alex y la calle por la que camina Michèle en la siguiente escena. En esta transición brusca de un plano a otro, en esa manera de dilatar el encadenado provocando un efecto que es menos fluido que el de un corte directo, queda perfectamente dibujado este violento choque de elementos.

En otro fragmento del filme vemos a Alex conduciendo una lancha por el río mientras Michèle hace esquí acuático. La escena es un estallido de cascadas de agua y de luz, donde la velocidad del movimiento y las pulsaciones de la cámara producen una imagen llena de desenfoques abstractos y de colores parpadeantes. Cuando Michèle vuelca, Alex también se lanza al Sena. Durante unos segundos, vemos en la pantalla la sobreimpresión de dos imágenes: el alboroto del agua provocado por el chapuzón de Alex y la calle por la que camina Michèle en la siguiente escena. En esta transición brusca de un plano a otro, en esa manera de dilatar el encadenado provocando un efecto que es menos fluido que el de un corte directo, queda perfectamente dibujado este violento choque de elementos.

En Los amantes del Pont-Neuf, Carax crea también una fascinante equivalencia entre la superficie líquida —maleable e informe— y la visión deficiente de Michèle —que da lugar a planos donde los objetos y los rostros pierden sus contornos y se convierten en una mezcla de colores y luces borrosas— pues, para Alex, la segunda tiene las propiedades de la primera. Mientras, para él, la visión defectuosa de Michèle es precisamente la que posibilita esa experiencia utópica y líquida que ambos comparten, para ella, es solo un tormento al que debe resignarse o, finalmente, superar. Alex sabe que la enfermedad degenerativa que padece Michèle es lo que la ha conducido al puente y teme que esa misma enfermedad (y la dependencia que conlleva) sea lo único que la mantiene a su lado. Este miedo es lo que empuja al protagonista a lanzar al río la cajita en la que guardan el dinero, a quemar los carteles con la foto de ella y, en definitiva, a esconderla de ese mundo al que perteneció una vez y ahora la reclama.

Los amantes del Pont-Neuf no se cuestiona si es posible que surja el amor entre Alex y Michèle porque la propia película es la celebración y la confirmación irrefutable de esto. La verdadera pregunta que late en el corazón del filme es: ¿puede sobrevivir este romance? ¿puede extenderse en el tiempo? Como Philippe Garrel, Carax es un cineasta maravillado ante el nacimiento del amor y atormentado por la amenaza de su muerte o de su desaparición.

¿Pueden las cuatro noches de un soñador trascender su condición de espejismo del deseo? ¿Pueden superar la categoría de mera contingencia? ¿Pueden desafiar la caducidad de una situación motivada por unas circunstancias pasajeras? Cuando Michèle visita a Alex en la cárcel, el filme da un hermoso giro a todas estas cuestiones y nos susurra su respuesta en las palabras de ella: “Pensé que te había olvidado. Pero durante semanas, cada noche, veía imágenes de ti. Por eso estoy aquí, mis sueños me han enviado”. Bajo la estela bressoniana, Carax funde al Dostoyevski de Noches blancas con el de Crimen y castigo e ilumina el extraño camino recorrido por estos amantes para encontrarse.

El desenlace de Los amantes del Pont-Neuf nos lleva de vuelta al puente y a ese gesto inaugural con el que empezó todo (Michèle pintando un retrato de Alex, él reconociéndose a través de la mirada de ella). El filme concede a los personajes esta segunda oportunidad: la posibilidad de retomar un amor que “será el mismo” pero “será diferente” porque ambos han cambiado. Sin embargo, cuando las campanas tocan las tres, Michèle, cual Cenicienta temerosa de perder su carroza y sus zapatos, le dice a Alex que debe marcharse, que necesita tiempo. Y es entonces cuando él ejecuta un movimiento impulsivo, una jugada inesperada que resultará decisiva.

Carax filma esto en seis planos que son una bella coreografía de acercamiento y resistencia, de duda y decisión, de lucha y caída. Primero, Alex, con la cámara tras su nuca, da un par de pasos por el pretil del puente mientras Michèle permanece al fondo, desenfocada. Después, con la cámara ya situada delante de él, vemos al personaje avanzar, cruzando el plano en diagonal. El contraplano de Michèle crea una hermosa rima de movimientos pues ella también avanza en dirección a Alex, pero más lentamente, vacilando. A continuación, otra imagen de Alex, muy parecida a la anterior, pero con la cámara más cerca de su rostro. En el quinto plano, Carax nos sorprende con una posición de cámara totalmente inesperada: el cielo negro ocupa toda la pantalla, Alex entra en plano por el lado derecho del encuadre y, cuando vemos a Michèle asomarse por la izquierda, él se lanza sobre ella y la rodea con sus brazos. Sus cuerpos luchan y se tambalean en el vacío de la noche, Michèle grita. Tras el corte, en un plano general que vuelve a modificar todas las coordenadas de la escena, vemos cómo los dos personajes, enredados, caen al río y chocan contra el agua.

Un gesto pequeño pero significativo: Michèle se tapa los ojos con las manos, como si tuviese miedo de que el agua fuese a dañarlos. Pero ese temor inicial se disipa rápidamente, desaparece al ser devorado por otras emociones e intuiciones. Los cuerpos de la pareja, absorbidos por las profundidades del río, se acercan y se alejan, se mueven de arriba abajo como en un baile grácil e ingrávido, se funden en un breve abrazo para volver a separarse enseguida. Durante doce segundos, arropados por la inmensidad acuática, Alex y Michèle no hacen otra cosa que mirarse a los ojos. Se trata de un momento de absoluta epifanía, de verdadero reconocimiento y clarividencia: ahora pueden ver.

El propio Leos Carax lo expresó de forma bella y concisa: el cine es “una lengua creada para aquellos que necesitan viajar al otro lado de la vida”. Y, desde su asombrosa ópera prima —Boy Meets Girl (1984)— hasta su obra más reciente —la flamante Holy Motors (2012)—, los filmes de Carax nunca han dejado de buscar obsesivamente nuevas e inventivas maneras de embarcarse en ese viaje.

© Cristina Álvarez López, octubre 2013

Les amants du Pont-Neuf: A Drama of Water and Stone

Click here for the Spanish version

“Don’t you know you can see the one you love in the water?”

L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

Les amants du Pont-Neuf (1991) is, in essence, a love story about two characters who do not belong to the same world. As happens again with Pierre (Guillaume Depardieu) and Isabelle (Katerina Golubeva) in Pola X (1999) – a film that, in many respects, can be seen as a skilful variation (darker, more radical, more desperate) on Les amants du Pont-Neuf – here, the relationship between Alex (Denis Lavant) and Michèle (Juliette Binoche) is only possible when one member of the couple – the one who comes from a wealthy family, brought up amidst culture and affluence – decides to abandon it all in order to be submerged in the universe of the other, to become part of a community of dispossessed souls to which they do not, in the first place, belong.

In Pola X, this crucial change in Pierre’s life is rendered as a plunge into the darkness of night, led by the ghostly, haunting voice of Isabelle. In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, by contrast, we do not witness this turning-point: as the film begins, Michèle has already left her past behind, and now wanders alone in the streets, with her sketchbook under her arm, her tattered clothes and eye patch.

In Carax’s Bad Blood (Mauvais sang, 1986), another Alex – once again played by Denis Lavant – is in pain, brought on by the “cement stomach” he has suffered since being in jail; to the beat of David Bowie’s “Modern Love”, he embarks on a desperate run in order to rid himself of that load. In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Alex maintains a constant struggle against all solid surfaces. In the opening sequence, Alex, lying on the pavement, places a hand on his neck and pushes his head from left to right, rubbing his forehead against the asphalt and making it bleed. Later, in the middle of a frenzied dance with Michèle, he stamps his feet on the stone while fireworks explode in the sky, falling like dew drops. Sometimes, this combat takes the form of a subtle challenge, such as when our hero does acrobatic stunts on the bridge, or climbs the metro corridor walls. But this effort by Alex to maintain an elastic, malleable body is always an attempt, perhaps unconscious, to transcend the solidity of surfaces, the impermeability of stone and steel: it is a cry of rebellion against everything that oppresses him.

In Carax’s Bad Blood (Mauvais sang, 1986), another Alex – once again played by Denis Lavant – is in pain, brought on by the “cement stomach” he has suffered since being in jail; to the beat of David Bowie’s “Modern Love”, he embarks on a desperate run in order to rid himself of that load. In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Alex maintains a constant struggle against all solid surfaces. In the opening sequence, Alex, lying on the pavement, places a hand on his neck and pushes his head from left to right, rubbing his forehead against the asphalt and making it bleed. Later, in the middle of a frenzied dance with Michèle, he stamps his feet on the stone while fireworks explode in the sky, falling like dew drops. Sometimes, this combat takes the form of a subtle challenge, such as when our hero does acrobatic stunts on the bridge, or climbs the metro corridor walls. But this effort by Alex to maintain an elastic, malleable body is always an attempt, perhaps unconscious, to transcend the solidity of surfaces, the impermeability of stone and steel: it is a cry of rebellion against everything that oppresses him.

To affirm that the Pont-Neuf is the setting that allows this love story of Alex and Michèle to happen would be to yield to a rather facile temptation. If there is anything that Carax’s film complicates to the max, it is this symbolic property that gives the bridge a status as passage, ‘communicating vessel’, or point of encounter between two characters and two worlds. If we accept that this setting is what shelters the characters’ love, we must also recognise that this place, equally, constrains their love. Les amants du Pont-Neuf avoids, at all cost, any romanticisation of ‘street life’; in particular, it completely rejects the spurious belief that equates homelessness with an existence free from all chains. In the film, the bridge is like a bourgeois home to Alex. Living in it exposes him to the same fantasies and the same threats that anyone would face: to own a home means, in turn, to be owned by it. While the jail that Alex ends up in near the film’s end becomes the place from which he will be definitively released, the Pont-Neuf is a prison without bars that our hero is frightened of leaving – because it is only when he is shut in there that he feels safe.

Consequently, Carax never films the bridge in terms of transit or access, but only as a limit. And the film completely inscribes itself within this border zone, even when it leaves the confines of this stage that gives it a title. Carax composes his shots to emphasise the line of stone that cuts through images, forming diagonals or horizontals that bisect the frame and split the screen into uneven halves. A margin between land and water, between the mundane, known land inhabited by the characters, and the magical, aquatic universe of sea or river.

The love between Alex and Michèle is born and grows in this border zone, but, unquestionably, its horizon is elsewhere: the characters stand upon stone, but seek another climate, one that is able to adapt to their bodies, to lessen and filter out the weight of their burdens. Clear, liquid surfaces are permeable, allowing and encouraging transit: these are the true passageways of the film. In order to give form to this drama of stone and water, Carax not only works on mise en scène and framing, but uses every element at his disposal. In this sense, as we shall see, the work of cinematography and editing (by, respectively, Jean-Yves Escoffier and Nelly Quettier, his frequent collaborators) is particularly striking.

In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, water brings with it a feeling of liberation that finds its ultimate expression in the finale, but is already prefigured in two of the film’s most beautiful sequences. In the first, Alex and Michèle escape to a beach and run naked along the shore – that other limit separating the world they live in from the destiny they long for. It is an ecstatic moment, infused with a wild, keen sense of joy. The following morning, an aerial angle, tracing a pendular movement, takes us from sea waves to snowy landscape. The resulting shot is strange, almost unreal; in it, the white of the foam and the snow are confused; we can scarcely distinguish where one material mass ends and the other begins.

In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, water brings with it a feeling of liberation that finds its ultimate expression in the finale, but is already prefigured in two of the film’s most beautiful sequences. In the first, Alex and Michèle escape to a beach and run naked along the shore – that other limit separating the world they live in from the destiny they long for. It is an ecstatic moment, infused with a wild, keen sense of joy. The following morning, an aerial angle, tracing a pendular movement, takes us from sea waves to snowy landscape. The resulting shot is strange, almost unreal; in it, the white of the foam and the snow are confused; we can scarcely distinguish where one material mass ends and the other begins.

In another fragment of the film, we see Alex piloting a speed boat along the Seine, with Michèle waterskiing behind him. The scene is an exploding cascade of water and light, in which the speed of movement and the trembling of the camera produce an image full of abstract blurs and flickering colours. When Michèle topples over, Alex dives into the water with her. For a few moments, we see two images superimposed on screen: the water churned up by Alex’s dive, and the street along which Michèle walks in the following scene. In this sudden transition from one shot to another, in this extended lap-dissolve whose effect is less fluid than a direct cut, the violent clash of different elements is perfectly conveyed.

In another fragment of the film, we see Alex piloting a speed boat along the Seine, with Michèle waterskiing behind him. The scene is an exploding cascade of water and light, in which the speed of movement and the trembling of the camera produce an image full of abstract blurs and flickering colours. When Michèle topples over, Alex dives into the water with her. For a few moments, we see two images superimposed on screen: the water churned up by Alex’s dive, and the street along which Michèle walks in the following scene. In this sudden transition from one shot to another, in this extended lap-dissolve whose effect is less fluid than a direct cut, the violent clash of different elements is perfectly conveyed.

In Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Carax also creates a fascinating equivalence between these liquid surfaces – malleable, unformed – and Michèle’s defective vision, which results in shots where objects and faces lose their contours and become a smudged mixture of colour and light. For Alex, it is precisely Michèle’s defective vision which allows the possibility of the utopian, liquid experience they share – whereas, for her, it is only a torment to be endured, or (eventually) overcome. Alex knows that the degenerative disease which Michèle suffers is what has brought her to the bridge, and to him; therefore, he fears that this disease (and the dependency it entails) is the only thing that keeps her by his side. This fear is what pushes Alex to hurl the box holding her money into the river, to burn the posters that picture her and, definitively, to hide her from the world to which she once belonged, and which now seeks to reclaim her.

Les amants du Pont-Neuf does not ask whether it is possible for love to occur between Alex and Michèle; the whole film is the celebration, the irrefutable confirmation of this as a fact. The real question at the beating heart of the film is: can this romance survive? Can it be prolonged through time? Like Philippe Garrel, Carax is a marvellous director of the ‘birth of love’, and just as haunted by the shadow of its death or disappearance.

Can these ‘four nights of a dreamer’ transcend their mirage-like state of desire? Can they surpass the category of mere contingency? Can they defy the expiry-date of a situation brought about by fleeting circumstance? When Michèle visits Alex in jail, the film gives a splendid spin to all these questions, and surprises us with her answer: “I thought I’d forgotten you. But every night, for weeks, I saw images of you. That’s why I’m here, my dreams sent me”. In the wake of Bresson, Carax fuses the Dostoyevsky of White Nights with the Dostoyevsky of Crime and Punishment, in order to illuminate the strange path along which these lovers will reunite.

The finale of Les amants du Pont-Neuf returns to the bridge and to the opening gesture that started it all (Michèle painting a portrait of Alex, him recognising himself through her eyes). The film gives its characters this second chance: the possibility of resuming a love that “will be the same” but also “will be different”, because both people have changed. However, when the church bells strike three, Michèle, like a Cinderella afraid to lose her carriage and her slipper, says to Alex that she must leave, that she needs time. And that is when Alex executes a most impulsive gesture, an unexpected but decisive move.

Carax films it in six shots that form a gorgeous choreography of approach and resistance, doubt and decision, fight and fall. First, Alex, with the camera at his back, takes a couple of steps along the bridge’s parapet, while Michèle stays fixed in the background, out of focus. Then, with the camera now positioned in front of Alex, we see him advance, crossing the frame diagonally. The reverse shot of Michèle creates a fine rhyme of motions, as she also moves towards Alex – only more slowly and hesitantly. Then another image of Alex, very similar to the previous angle on him, but with the camera up close to his face. In the fifth shot, Carax surprises us with a totally unexpected camera position: a dark sky fills the entire screen, Alex enters shot from the right side of the frame and, once Michèle has entered from the left, he throws himself on her, gathering her up in his arms. Their bodies struggle and lurch in this void of night, and Michèle screams. Then a cut to a wide shot that modifies every one of the scene’s coordinates, as we see how these two characters, entangled, fall to the river and hit its surface.

A small but significant gesture: Michèle covers her eyes with her hands, as if fearing that the water might damage them. But this initial dread rapidly dissipates, vanishing under the force of other emotions and intuitions. The bodies of the couple, absorbed by the river’s depths, approach and retreat from each other, moving up and down as in a graceful, weightless dance, and share a brief hug before quickly separating. For all of twelve seconds, surrounded by the immensity of water, Alex and Michèle do nothing but stare into each other’s eyes. It is a moment of absolute epiphany, of true recognition, even clairvoyance: now they can truly see.

Leos Carax himself expressed it beautiful and concisely: cinema is “a language created by those who need to travel to the other side of life”. And, from his astonishing debut Boy Meets Girl (1984) right up to his latest, Holy Motors (2012), Carax’s films have never ceased obsessively searching out new, inventive ways of embarking on this voyage.

Translated from the Spanish by Adrian Martin

Original text © Cristina Álvarez López October 2013 || English translation © Adrian Martin November 2013