El quimérico inquilino

¿No me reconoces?

Click here for the English version

El quimérico inquilino (The Tenant, Roman Polanski, 1976) es, esencialmente, una historia sobre la identidad, sobre el reconocimiento de otro yo en un cuerpo que ya no se reconoce a sí mismo. Centrándome en esta idea, en mi ensayo audiovisual quiero proponer una nueva interpretación de la narrativa del filme.

El quimérico inquilino comienza tras el primer intento de Simone por escapar. Es un intento frustrado: pese a su salto desde un tercer piso, Simone aún sigue viva, atrapada en una cama de hospital, cubierta por vendas como una momia. Es bien sabido que el rito de momificación intenta preservar el cuerpo intacto. Para Simone, es como la ley de la venganza: mantener su cuerpo intacto significa mantener intacta la prisión del alma.

Lo único que vemos del rostro de Simone son sus ojos y su boca. Dos órganos que, alimentados por el inconsciente, reconstruyen la realidad al tiempo que la reproducen. Pero, también, dos órganos que, por sí solos, no pueden indicarnos el género —masculino o femenino— de una persona. Simone es, en realidad, solo un alma.

En tanto que lesbiana, Simone ama a las mujeres y no a los hombres; quizás está enamorada de su amiga Stella. Cuando recibe su visita en el hospital, Simone está buscando, una vez más, la manera de amarla.

He construido mi ensayo audiovisual con la intención de demostrar que todo lo que sucede es parte del segundo plan de Simone para escapar de su cuerpo. Mi pieza, como el filme, tiene una estructura circular. Comienza con Simone en el hospital y termina en el mismo lugar. Pero, a diferencia del filme original, aquí no es Trelkovsky quien termina hospitalizado, sino de nuevo (y siempre) Simone. Lo que vemos es la proyección astral de Simone dentro del cuerpo de Trelkovsky.

Tras la introducción, el ensayo continúa retratando la transformación de Trelkovsky en Simone. Una serie de movimientos que se solapan (luces que se encienden/se apagan; ponerse/quitarse la peluca) enfatizan el contraste entre el cuerpo y el alma: entre las acciones rutinarias de Simone y las reacciones trastornadas del hombre cuyo cuerpo habita. Una identidad es violada.

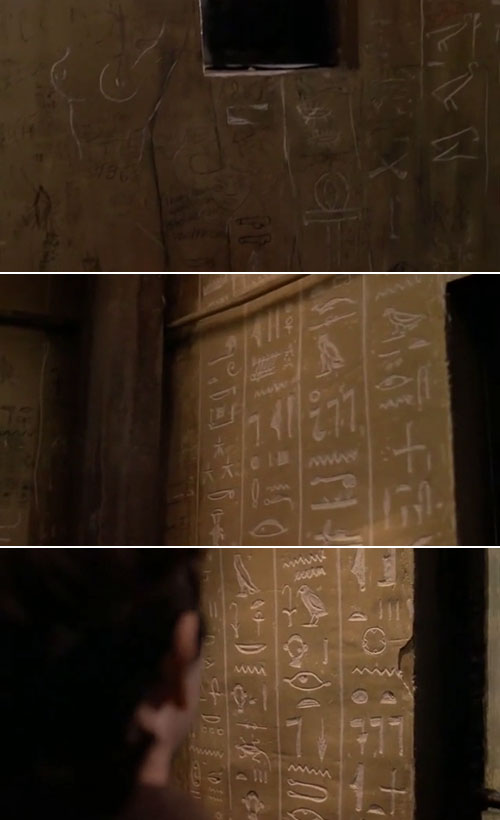

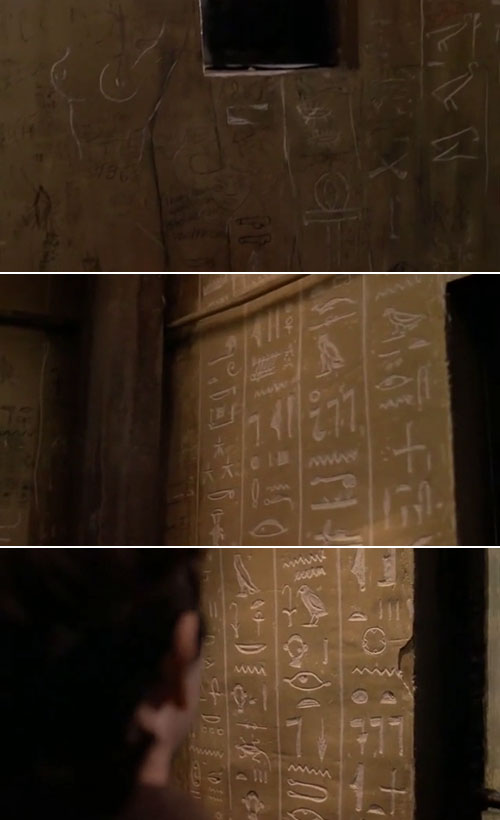

En la segunda parte de mi pieza reúno indicios sobre la sexualidad de Trelkovsky/Simone y sobre los deseos que condujeron a Simone al suicidio, así como signos que apuntan al plan ingeniado por ella a partir de su pasión por la religión egipcia. En el baño compartido del condominio hay símbolos egipcios grabados en las paredes. Reconocemos el dibujo de un cuerpo femenino cubierto por jeroglíficos. Estos jeroglíficos incluyen la Cruz Ankh, uno de los símbolos egipcios más famosos, fuertemente vinculado a la sexualidad. El extremo superior de la cruz es el principio femenino (Ioni), el brazo vertical es el principio fálico masculino (Lingam). La cruz Ankh simboliza también la muerte como renacimiento, igual que en el dibujo de Simone. Otro de los símbolos que podemos observar es el Ojo de Horus que hace referencia a los dos hemisferios del cerebro —uno controla las funciones racionales mientras el otro está relacionado con la imaginación—. ¿Es El quimérico inquilino una plasmación del viaje racional de Trelkovsky hacia la locura o del trayecto imaginario de Simone en pos de la liberación?

Antes de la repetición de la misma escena del hospital con la que inicio mi pieza, he encadenado una serie de momentos en que distintos objetos (zapatos, naranjas, cristales) caen ante la mirada de Trelkovsky, prefigurando un final anunciado.

De nuevo, Simone está en su cama de hospital: esta vez la escena es subjetiva, filmada desde su punto de vista. Todo vuelve al comienzo. Una frase, repetida con frecuencia en el filme, conecta la trama del ensayo audiovisual. La pregunta de Stella —“¿No me reconoces?”— trae a la mente de Simone el periplo que la ha llevado a su encarcelación cual momia egipcia. Víctima de su propio plan, Simone no puede evitar mirar al mundo, encerrada en la tumba de su cuerpo.

Traducción al español: Cristina Álvarez López

Texto original © Stefano Notaro, julio 2015 | Traducción al español © Cristina Álvarez López, julio 2015

![]()

The Tenant

Don’t You Recognise Me?

Click aquí para la versión en español

The Tenant (Roman Polanski, 1976) is, essentially, a story about identity, the recognition of another self in a body that cannot recognise itself anymore. Highlighting this motif, in my audiovisual essay I have tried to give a new, personal interpretation of the film’s narrative.

The movie starts after the first escape attempt made by Simone. It’s a failed attempt: despite her jump from the third floor, Simone is still alive, stuck in a hospital bed, covered with bandages like a mummy. As is well known, the mummification rite aims to keep a body intact. For Simone, it is like the law of revenge: to keep a body intact is to keep the soul’s prison intact.

The only thing that we can see of Simone’s face is her eyes and mouth – the two organs that, passing from the unconscious, rework reality while reproducing it. But they are also two organs that cannot indicate whether someone is a man or a woman. Simone is, in fact, only a soul.

As a lesbian, Simone loved women rather than men; perhaps she loved her friend Stella. When Stella meets her in the hospital, Simone is looking for another way to love her once more.

I’ve constructed my audiovisual essay in order to prove that everything that happens is part of Simone’s second plan to escape her body. My piece, like the film, has a circular structure. It starts with Simone in the hospital and ends there as well – but, unlike the original film, here it is not Trelkovsky who is hospitalised, but once again (and always) Simone. What we see is the astral projection of Simone inside Trelkovsky’s body.

After its intro, my essay continues with the transformation of Trelkovsky into Simone. A series of overlapping movements (lights on/lights off, wig on/wig off) emphasises the contrast between body and soul: between the routine actions of Simone and the disturbed responses of the man whose body she occupies. An identity is violated.

In the essay’s second part, I gather the evidence of Trelkovsky/Simone’s sexuality and the desires that led Simone to suicide – followed by several signs pointing to her plan inspired by her passion for Egyptian religion. In the shared bathroom of the condominium, there are Egyptian symbols carved on the wall. The drawing of a female body covered with hieroglyphics is recognisable. These hieroglyphics include the Ankh Cross, which is one of the most famous Egyptian symbols strongly linked to sexuality. The top of the cross is the feminine principle, the Yoni, while the vertical arm is the phallic male principle, the Lingam. It also symbolises death as rebirth, as in Simone’s drawing. As well, we can spot the Eyes of Horus: this is an image relating to the two hemispheres of the brain, one of which controls the rational functions, while the other is linked to imagination. Is what we see in the film Trelkovsky’s rational journey into madness, or Simone’s imaginary trip toward freedom?

Before the repetition of the hospital scene that opens the piece, I link a series of moments in which several objects (shoes, oranges, glass) fall in front of Trelkovsky’s eyes, announcing his fateful end.

Again, Simone is in the hospital bed: this time the scene is subjective, from her point of view. It ends where it started. A phrase, which recurs in the film, connects the plot of the audiovisual essay. Stella asks: “Don’t you recognise me?”, bringing to Simone’s mind the journey that led her to be imprisoned like an Egyptian mummy. The victim of her own plan, Simone cannot help but look at the world, trapped in the tomb of her body.

Edited by Adrian Martin

© Stefano Notaro, July 2015